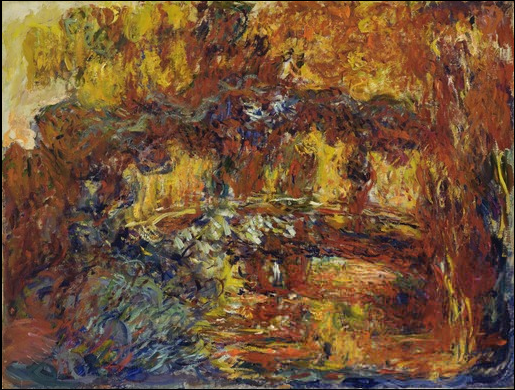

Painting, as any Art History 101 lecturer will tell you, found the motivation to turn abstract when photography trumped it in the game of lifelike representation. But what pushes photography, and even motion pictures, to give abstraction a try? The vast majority of films made today still represent reality in some basically direct fashion, but almost since the first appearance of the medium, certain artists have tried to push it in other directions. If you know the work of only one abstract filmmaker, you probably know the work of Stan Brakhage, craftsman of such vivid and distressed cinematic experiences as Cat’s Cradle and Dog Star Man. But who preceded him?

The title of the very first abstract filmmaker has been disputed, but we at least know who made several early abstract masterpieces. Today we present two of them, Hans Richter’s Rhythmus 21, made in 1921, and from three years later, Viking Eggeling’s Symphonie Diagonale. “Clocking in at just over three minutes, it’s a significant departure from the newsreels, romances, cliff-hangers, and penny-dreadfuls that made up the bulk of film production in the early 20s,” writes the Getty’s Jannon Stein of Richter’s hypnotically geometric picture, “the first decade in which the film industry began to play a major economic and cultural role around the world.”

But Richter, Stein continues, “credited his friend Viking Eggeling with the idea of exploring the possibilities for abstract animation. In fact, they’d worked together on a series of paintings on scrolls that preceded both of Richter’s first films, as well as Symphonie Diagonale,” which you can watch just above. This version opens with an endorsement from no less daring a mind than architect-artist-theoretician Frederick John Kiesler, who describes it as “the best abstract film yet conceived” and “an experiment to discover the basic principles of the organization of time intervals in the film medium.” I, personally, would call it something like a pure shot of the art-deco aesthetic which we now know, of course, not from the film it produced in the 20s, but the architecture.

That may excite you or it may not, but words have never quite suited the abstract. If Richter, Eggeling, Brakhage, or any who came between them or have come after them share a mission, that mission involves making movies that no words can really describe. Eggeling would pass on the year after Symphonie Diagonale, but Richter would go on to a long life and career that included other projects meant to take film beyond its conventional uses, such as 1947’s “story of dreams mixed with reality,” Dreams that Money Can Buy. Even now, in the 21st century, it seems that the medium has a long way to go before it makes use of all the creative space available to it — which should only encourage the next Richters and Eggelings of the world.

Symphonie Diagonale and Rhythmus 21 will be added to our collection, 4,000+ Free Movies Online: Great Classics, Indies, Noir, Westerns, Documentaries & More.

Related Content:

Watch Dreams That Money Can Buy, a Surrealist Film by Man Ray, Marcel Duchamp, Alexander Calder, Fernand Léger & Hans Richter

CBS Evening News with Walter Cronkite Introduces America to Underground Films and the Velvet Underground (1965)

Man Ray and the Cinéma Pur: Four Surrealist Films From the 1920s

Un Chien Andalou: Revisiting Buñuel and Dalí’s Surrealist Film

The Hearts of Age: Orson Welles’ Surrealist First Film (1934)

The Seashell and the Clergyman: The World’s First Surrealist Film

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.