In her brief 34 years, Lorraine Hansberry left a formidable legacy as the first African-American and the youngest playwright to win the coveted New York Critics’ Circle Award for A Raisin in the Sun. (It was also the first play by a black writer to be produced on Broadway.) What’s more, Hansberry was a committed civil rights campaigner, from a family who had fought housing segregation in the Supreme Court. She herself organized with Martin Luther King, Jr., Harry Belafonte, Lena Horne, James Baldwin, and many others; wrote for Paul Robeson’s Freedom; and joined the first lesbian civil rights organization, the Daughters of Bilitis, contributing to their magazine, The Ladder.

Hansberry was indeed “Young, Gifted, and Black,” which also happens to be the title of an autobiography published after her death from pancreatic cancer in 1965, and of a posthumously produced play. But the title has maybe most famously lived on in a tribute to Hansberry by her friend, the prodigiously gifted Nina Simone. Among Simone’s many mentors, Hansberry “offered her a special bond,” writes Claudia Roth Pierpont at The New Yorker, and pushed her into activism. “We never talked about men or clothes,” Simone wrote in her memoir, I Put a Spell on You, “It was always Marx, Lenin and revolution—real girls’ talk.” After the 1963 Baptist Church bombing in Birmingham, Simone dedicated herself to the movement with a passion for justice and liberation.

And yet, “for every lyric about lynchings and the struggle for equality,” notes the Blanton Museum, “Simone would write another about freedom and black pride, reinforcing her belief that African American men and women should know the beauty of their blackness.” As she put it in an interview, “My job is to somehow make [black people] curious enough, or persuade them, by hook or crook, to get them more aware of themselves and where they came from and what is already there.” What was already there included the work of friends like James Baldwin and Lorraine Hansberry, from whom Simone drew “To Be Young, Gifted and Black,” one of the “most triumphant anthems of the black pride movement of the 1970s.”

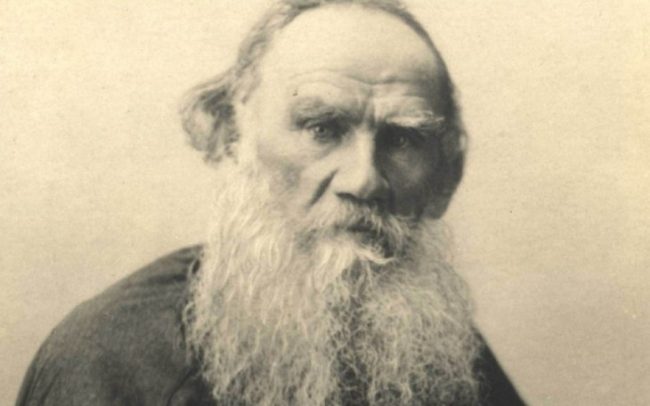

At the top of the post, you can see Simone sing the song to four young kids on a 1972 episode of Sesame Street, bringing them the news: “There’s a world waiting for you.” As she announces in the song itself, “We must begin to tell our young” the importance of their culture and history. The young responded with gratitude for Simone’s advocacy. In the short Sesame Street clip, the four adorable kids look on admiringly, and one girl sings along. The inspiration for the song came not only from Hansberry’s influence on Simone’s political consciousness, but also from a photograph of Hansberry she saw in the New York Times.

The picture, “caught hold of me,” Simone says in the brief interview clip above, “I remember getting a feeling in my body.… I knew what I wanted it to say in essence.… I really think that she gave it to me.” After the short interview, you can see Simone perform the song in a 1969 session at Morehouse College, to rapturous applause from the audience. “To Be Young, Gifted and Black” has been covered by duo Bob & Marcia, Donny Hathaway, Aretha Franklin, and—most recently, Solange Knowles. Though none of these artists have had the intimate, personal connection to the lyrics and their inspiration that Nina Simone did, all of them have helped transmit her message. Even in the face of gross injustice and seemingly implacable opposition to equality and civil rights, “There’s a world waiting for you / This is a quest that’s just begun.”

Related Content:

Nina Simone Sings Her Breakthrough Song, ‘I Loves You Porgy,’ in 1962

Watch a New Nina Simone Animation Based on an Interview Never Aired in the U.S. Before

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness