Twenty years ago a strong academic left in universities all over the world spoke to political culture the way that a globalized nationalist far-right seems to now. Among public intellectuals in the U.S., Richard Rorty’s name held particular sway. Yet in his contrarian 1998 book Achieving Our Country, Rorty argued against the participation of philosophy in politics. A member of the so-called “Old Left,” or what he called the “reformist left,” Rorty took on the “Cultural Left” in ways we now hear in (often bitter) debates between similar camps. In the course of his attacks, he made the uncanny prediction above.

The cultural left, wrote Rorty, had come “to give cultural politics preference over real politics, and to mock the very idea that democratic institutions might once again be made to serve social justice.” He foresaw cultural politics on the left as contributing to a tidal wave of resentment that would one day result in a time when “all the sadism which the academic left has tried to make unacceptable to its students will come flooding back.”

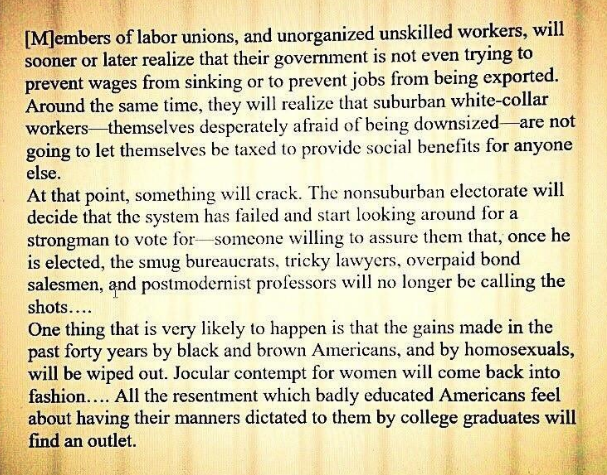

As democratic institutions fail, he writes in the quote above:

[M]embers of labor unions, and unorganized unskilled workers, will sooner or later realize that their government is not even trying to prevent wages from sinking or to prevent jobs from being exported. Around the same time, they will realize that suburban white-collar workers—themselves desperately afraid of being downsized—are not going to let themselves be taxed to provide social benefits for anyone else.

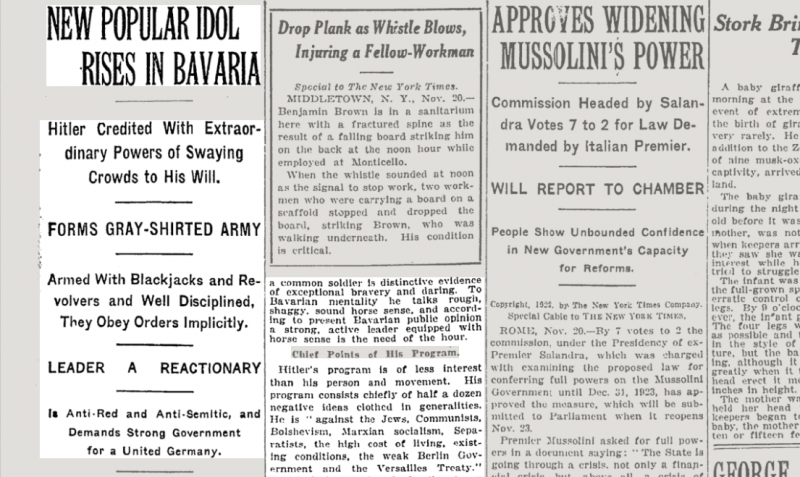

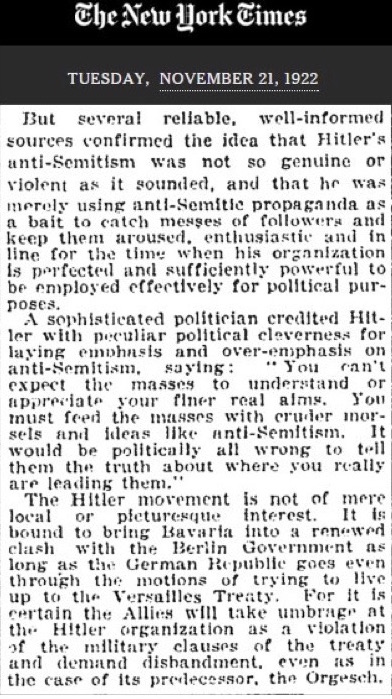

At that point, something will crack. The nonsuburban electorate will decide that the system has failed and start looking around for a strongman to vote for—someone willing to assure them that, once he is elected, the smug bureaucrats, tricky lawyers, overpaid bond salesmen, and postmodernist professors will no longer be calling the shots. A scenario like that of Sinclair Lewis’ novel It Can’t Happen Here may then be played out. For once a strongman takes office, nobody can predict what will happen. In 1932, most of the predictions made about what would happen if Hindenburg named Hitler chancellor were wildly overoptimistic.

One thing that is very likely to happen is that the gains made in the past forty years by black and brown Americans, and by homosexuals, will be wiped out. Jocular contempt for women will come back into fashion. The words [slur for an African-American that begins with “n”] and [slur for a Jewish person that begins with “k”] will once again be heard in the workplace. All the sadism which the academic Left has tried to make unacceptable to its students will come flooding back. All the resentment which badly educated Americans feel about having their manners dictated to them by college graduates will find an outlet.

He also then argues, however, that this sadism will not solely be the result of “economic inequality and insecurity,” and that such explanations would be “too simplistic.” Nor would the strongman who comes to power do anything but worsen economic conditions. He writes next, “after my imagined strongman takes charge, he will quickly make his peace with the international superrich.”

Rorty blamed the Marxist New Left for “retreating from pragmatism into theory,” wrote The New York Times in its review of Achieving Our Country. He felt the cultural left had abandoned the “American experiment as secular, anti-authoritarian and infinite in possibilities,” such as “Whitman idealized as loving relationships and Dewey as good citizenship.” The Times wrote then that Rorty’s predictions above were a form of “intellectual bullying.” We can take our dystopian futures from sci-fi novelists and filmmakers, but when philosophers “haruspicate or scry,” as T.S. Eliot wrote in “The Dry Salvages,” we tend to dismiss it as the “usual / Pastimes and drugs, and features of the press.”

The eminent Stanford professor exhorted his contemporaries to leave behind “semiconscious anti-Americanism” and embrace pragmatic civil engagement, and did so by offering up examples from American literature and philosophy that all had fierce activist strains. Excoriating one kind of life of the mind, Rorty can’t help but offer another. “What does Rorty offer as a solution?” asked the Times review, “Not really very much.” Perhaps not to politicians. But to the postmodern academics and writers he accused, he offers up as counter examples Walt Whitman, John Dewey, and—as Rorty noted in an interview—James Baldwin, whose “use of the phrase… achieving our country” inspired his book’s title, Achieving Our Country.

Related Content:

John Searle on Foucault and the Obscurantism in French Philosophy

Huxley to Orwell: My Hellish Vision of the Future is Better Than Yours (1949)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness.