When his short and (by his own account) often miserable life came to an end in 1950, could the English political writer Eric Arthur Blair have known that he would not just become a household name, but remain one well over half a century later? Given his adoption of the memorable nom de plume George Orwell, we might say he had an inkling of his literary legacy’s potential. Still, he claimed to choose it for no grander reason than that it sounded like “a good round English name,” and would have loathed the pretense he sensed in the use of the phrase “nom de plume,” or, for that matter, any other of conspicuously foreign provenance.

The attitudes that shaped the author of Animal Farm and 1984 come out in this animated introduction to Orwell’s life and work, newly published by Alain de Botton’s School of Life. In explaining the motivations of this “most famous English language writer of the 20th century,” de Botton quotes from the essay “Why I Write,” wherein Orwell, with characteristic clarity, lays out his mission “to make political writing into an art. My starting point is always a feeling of partisanship, a sense of injustice. When I sit down to write a book, I do not say to myself, ‘I am going to produce a work of art.’ I write it because there is some lie that I want to expose, some fact to which I want to draw attention, and my initial concern is to get a hearing.”

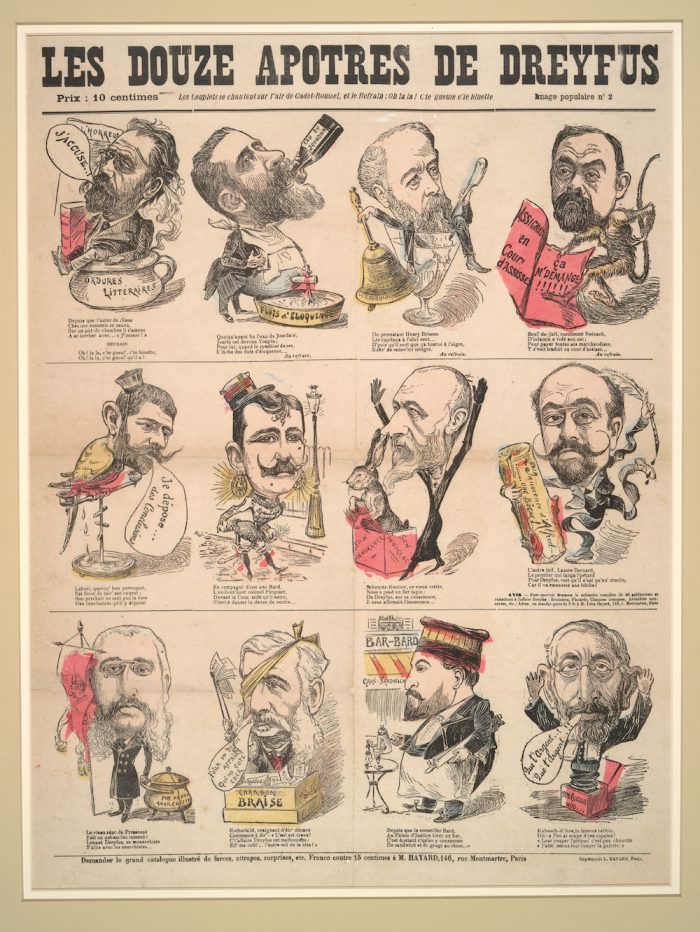

Orwell hated his fellow intellectuals, whom he accused of “a range of sins: a lack of patriotism, resentment of money and physical vigor, concealed sexual frustration, pretension, and dishonesty.” He loved “the ordinary person” and the lives led by those “not especially blessed by material goods, people who work in ordinary jobs, who don’t have much of an education, who won’t achieve greatness, and who nevertheless love, care for others, work, have fun, raise children, and have large thoughts about the deepest questions in ways Orwell thought especially admirable.” Though raised middle-class and educated at Eton, Orwell eschewed university and believed that “the average pub in a coal-mining village contained more intelligence and wisdom than the British Cabinet or the high table of an Oxbridge college.”

One might want to call such an intellectual a poseur or even a sort of fetishist, but Orwell backed up his pronouncements about the superiority of the working class with his years spent living and working in it, and, with books like Down and Out in Paris and London and The Road to Wigan Pier, writing about it. He praised newspaper comics, country walks, dancing, Charles Dickens, and straightforward language, all of which informed the attacks on ideology and authoritarianism that would keep his writing meaningful for future generations. The holiday season now upon us makes another work of Orwell’s especially relevant: his Christmas pudding recipe, one blow in his lesser-known struggle to, as the London-based de Botton puts it, write “bravely in defense of English cooking” — a project which would, by itself, qualify him as a champion of the underdog.

Related Content:

George Orwell Explains in a Revealing 1944 Letter Why He’d Write 1984

For 95 Minutes, the BBC Brings George Orwell to Life

George Orwell’s Final Warning: Don’t Let This Nightmare Situation Happen. It Depends on You!

What “Orwellian” Really Means: An Animated Lesson About the Use & Abuse of the Term

Try George Orwell’s Recipe for Christmas Pudding, from His Essay “British Cookery” (1945)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.