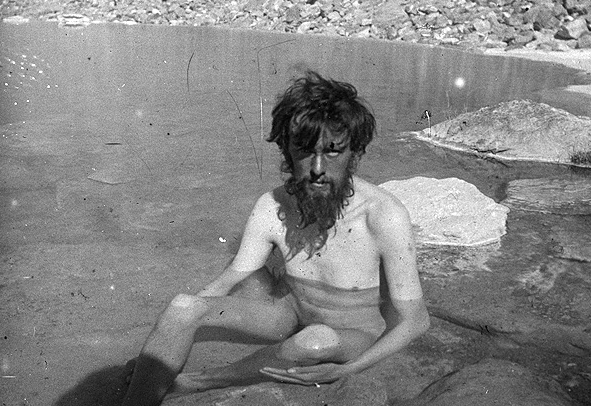

Image by Jules Jacot Guillarmod, via Wikimedia Commons

Last week, we brought you a rather strange story about the rivalry between poet William Butler Yeats and magician Aleister Crowley. Theirs was a feud over the practices of occult society the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn; but it was also—at least for Crowley—over poetry. Crowley envied Yeats’ literary skill; Yeats could not say the same about Crowley. But while he did not necessarily respect his enemy, Yeats feared him, as did nearly everyone else. As Yeats’ biographer wrote a few months after Crowley’s death in 1947, “in the old days men and women lived in terror of his evil eye.”

The press called Crowley “the wickedest man in the world,” a reputation he did more than enough to cultivate, identifying himself as the Anti-Christ and dubbing himself “The Beast 666.” (Crowley may have inspired the “rough beast” of Yeats’ “The Second Coming.”) Crowley did not achieve the literary recognition he desired, but he continued to write prolifically after Yeats and others ejected him from the Golden Dawn in 1900: poetry, fiction, criticism, and manuals of sex magic, ritual, and symbolism—some penned during famed mountaineering expeditions.

Throughout his life Crowley was variously a mountaineer, chess prodigy, scholar, painter, yogi, and founder of a religion he called Thelema. He was also a heroin addict and by many accounts an extremely abusive cult leader. However one comes down on Crowley’s legacy, his influence on the occult and the counterculture is undeniable. To delve into the history of either is to meet him, the mysterious, bizarre, bald figure whose theories inspired everyone from L. Ron Hubbard and Anton LaVey to Jimmy Page and Ozzy Osbourne.

Without Crowley, it’s hard to imagine much of the dark weirdness of the sixties and its resulting flood of cults and esoteric art. For some occult historians, the Age of Aquarius really began sixty years earlier, in what Crowley called the “Aeon of Horus.” For many others, Crowley’s influence is inexplicable, his books incoherent, and his presence in polite conversation offensive. These are understandable attitudes. If you’re a Crowley enthusiast, however, or simply curious about this legendary occultist, you have here a rare opportunity to hear the man himself intone his poems and incantations.

“Although this recording has previously been available as a ‘Bootleg,’” say the CD liner notes from which this audio comes, “this is its first official release and to the label’s knowledge, contains the only known recording of Crowley.” Recorded circa 1920 on a wax cylinder, the audio has been digitally enhanced, although “surface noise may be evident.” Indeed, it is difficult to make out what Crowley is saying much of the time, but that’s not only to do with the recording quality, but with his cryptic language. The first five tracks comprise “The Call of the First Aethyr” and “The Call of the Second Aethyr.” Other titles include “La Gitana,” “The Pentagram,” “The Poet,” “Hymn to the American People,” and “Excerpts from the Gnostic Mass.” (Find a complete tracklist at Allmusic.)

It’s unclear under what circumstances Crowley made these recordings or why, but like many of his books, they combine occult liturgy, mythology, and his own literary utterances. Love him, hate him, or remain indifferent, there’s no getting around it: Aleister Crowley had a tremendous influence on the 20th century and beyond, even if only a very few people have made serious attempts to understand what he was up to with all that sex magic, blood sacrifice, and wickedly bawdy verse.

Aleister Crowley The Great Beast Speaks 1920 — 1936 is available on Spotify. If you need to download Spotify’s software, get it here. It will be added to our list, 1,000 Free Audio Books: Download Great Books for Free.

Related Content:

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness