Image by Michiel Hendryckx, via Wikimedia Commons

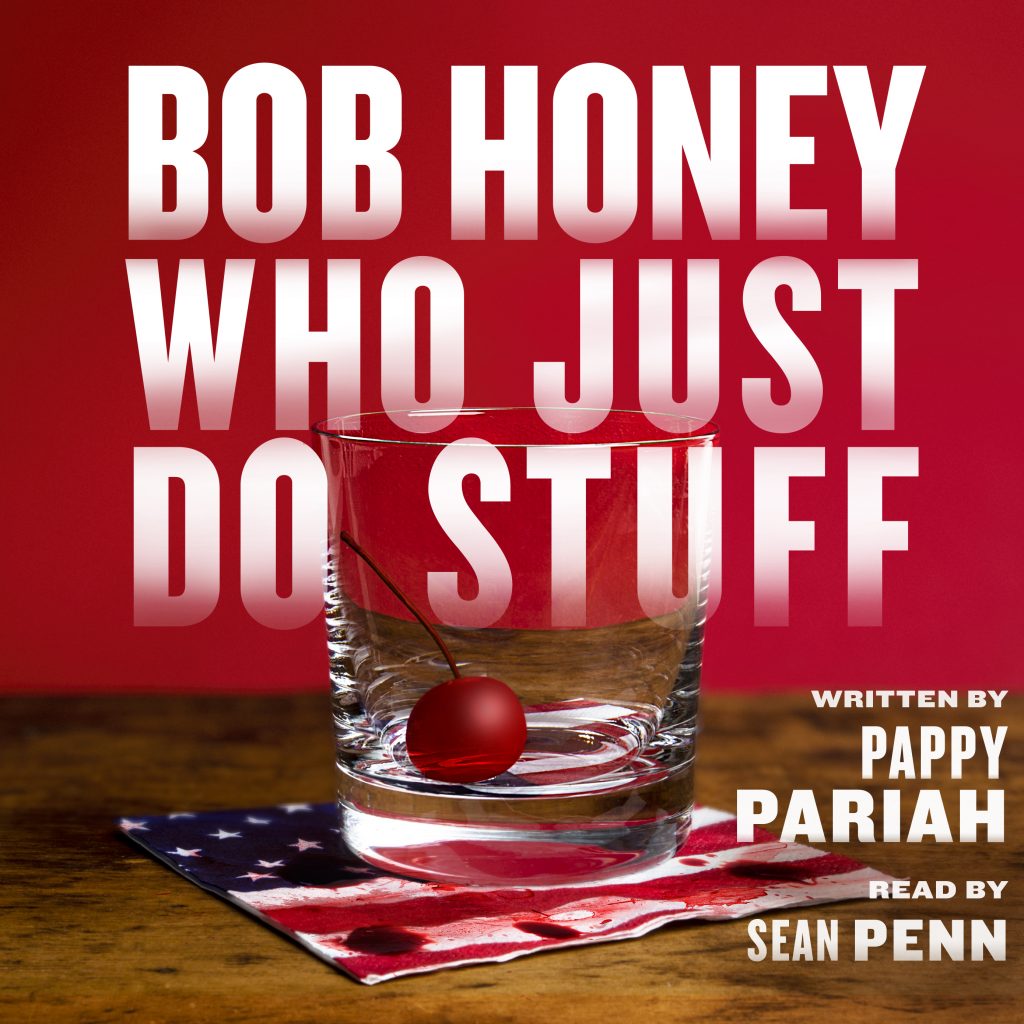

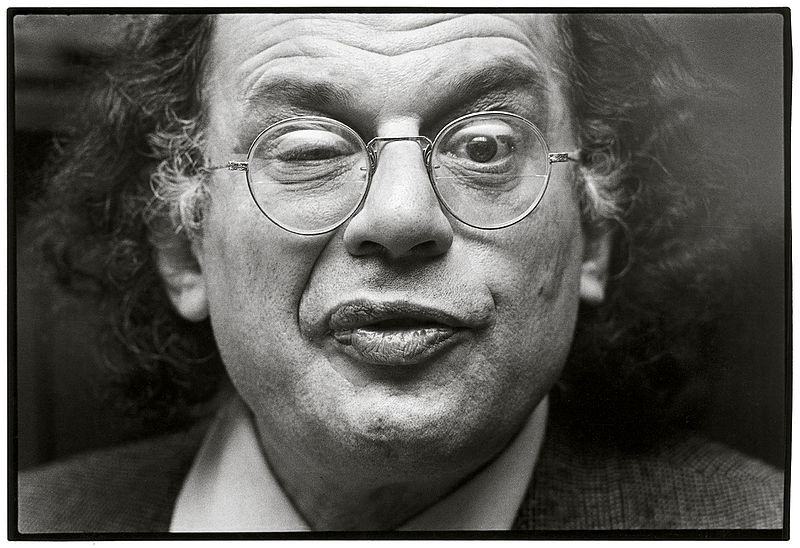

A peek at the photos on a realtor’s listing for a New York City one bedroom apartment formerly occupied by Beat poet Allen Ginsberg is a dispiriting reminder of how much the East Village has changed.

And that listing is over six years old!

Daniel Maurer, the editor of Bedford + Bowery, and a Ginsberg fan whom history has compelled to take over a portion of his hero’s formerly sprawling digs, wrote amusingly of shoddy renovations and his upstairs neighbor, punk rock icon Richard Hell:

Orlovsky’s name is still on the mailbox – which is just about the only thing still around from his day. After his death, the place was gut renovated with luxurious modern amenities like a mini fridge that comes up to mid-thigh and a stove that’s so tiny and ineffectual I just use it for cookbook storage. Soon after I moved in I took a trip to Ikea and recognized my kitchen cabinets there.

That’s why I was amused to read a piece in the Wall Street Journal … in which my upstairs neighbor, Richard Hell, talked about his rent-stabilized two-bedroom apartment and its “funkiness that you don’t find in Manhattan much anymore.”

Hell describes his “worn unvarnished wood floors that groan when you walk on them, cracks in the plaster walls, sagging original moldings.” That’s exactly what I was looking for in an apartment two years ago.

Maurer is far from alone in the desire to edge closer to a bygone cultural moment. Radio producer Pejk Malinovski spent three years crafting Passing Stranger, a site-specific audio tour of the East Village poetry scene, below.

A Dane who relocated to New York in 2003, Malinovski was intrigued by the scene-related anecdotes of his friend, poet Ron Padgett, who pointed out his former haunts on strolls about the neighborhood. His interest piqued, Malinovski immersed himself in Daniel Kane’s All Poets Welcome, The Lower East Side Poetry Scene in the 1960’s, another history that comes fortified with archival audio clips.

Filmmaker Jim Jarmusch, a longtime Lower East Side resident who studied with poet Kenneth Koch in his youth, was tapped to provide the audio tour’s narration, with music compliments of composer John Zorn, the artistic director of The Stone, an experimental East Village performance space. Below, Jarmusch explains what attracted him to the project:

No matter if geographic constraints prevent you from downloading Malinovski’s tour for a two mile, 90 minute amble around the much-changed East Village. In some ways, the virtual tour is better. Rather than trying to take it all in in a single, pre-plotted session, you’re free to wander at will, enjoying such interactive features as maps and photos, in addition to interviews, readings, and reminiscences.

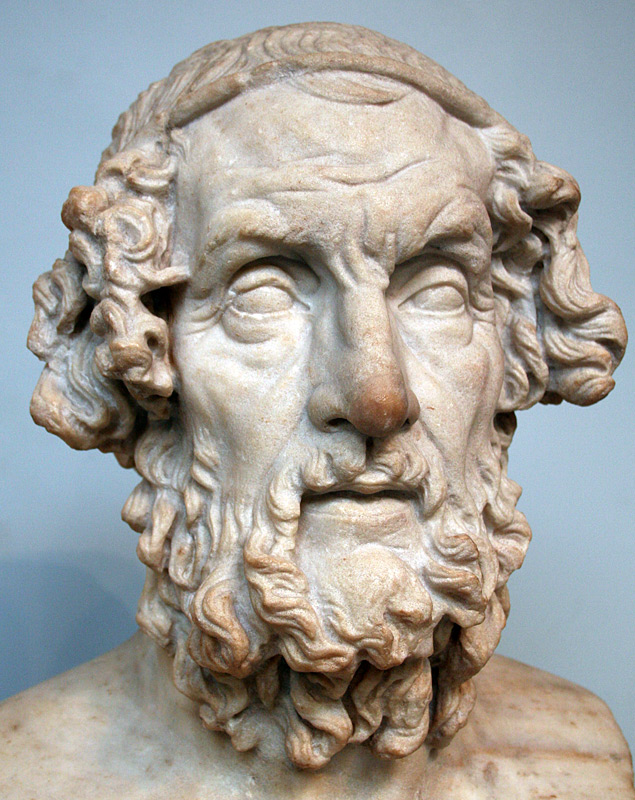

The 10th stop on the tour deposits you across the street from 437 East 12th Street, Ginsberg’s aforementioned former residence, on the steps of a church that no longer exists. Mary Help of Christians Roman Catholic Church was demolished shortly after Passing Stranger hit the streets, but its memory lives on thanks to its celebrated appearance in Ginsberg’s work:

Fourth Floor, Dawn, Up All Night Writing Letters

Pigeons shake their wings on the copper church roof

out my window across the street, a bird perched on the cross

surveys the city’s blue-grey clouds. Larry Rivers

‘ll come at 10 AM and take my picture. I’m taking

your picture, pigeons. I’m writing you down, Dawn.

I’m immortalizing your exhaust, Avenue A bus.

O Thought, now you’ll have to think the same thing forever!

- Allen Ginsberg, New York, June 7, 1980

Ginsberg himself is brought to vivid life by his secretary and fellow poet, Bob Rosenthal, who recalls how visitors would call up from the street, then wait for Ginsberg to toss down keys, wrapped in a dirty sock. He also name checks Mr. Buongiorno, the 437 East 12th St neighbor who served as Mary Help of Christians’ bell ringer.

You can hear those bells in the background of your Passing Stranger tour, though producer Malinovski uses ambient sound sparingly, to avoid overwhelming those using the tour on the noisy streets of the actual East Village.

You can download the full walking tour of Passing Stranger—named for Walt Whitman’s opening salutation in “To a Stranger”—here.

Explore Passing Stranger’s trivia-filled interactive website—featuring audio from Amiri Baraka, Hettie Jones, Eileen Myles, and Jack Kerouac, among others—here.

Poems included on the Passing Stranger audio tour of the East Village, in order of appearance:

Kenneth Koch, “To my Audience” (excerpt)

Frank O’Hara, Ode to Joy (To hell with it) (excerpt)

Ted Berrrigan “Dear Margie, Hello”

Ron Padgett “Poema del City from Toujours l’amour”

Walt Whitman, “To a Stranger”

Taylor Mead, “Motorcycles”

Bernadette Mayor, “Sonnet (You jerk, you didn’t call me up)”

Diane Di Prima, “Revolutionary Letters” (excerpt)

Galway Kinnell, “The Avenue Bearing the Initial of Christ” (excerpt)

Miquel Piñero, “A Lower East Side Poem” (excerpt)

Jack Kerouac, “American Haiku” (excerpt)

Bill Berkson / Frank O’Hara, “Song Heard Around St. Bridget’s”

John Ashbery, “Just Walking Around, from A Wave”

Joe Brainard, “I Remember” (excerpt)

Alice Notley, “10 Best Comic Books”

WH Auden, “September 1, 1939” (excerpt)

Anne Waldman, “Fast Speaking Woman” (excerpt)

Lewis Warsh, “Eye Contact” (excerpt)

Dick Gallup / Ted Berrigan, “80th Congress”

Abraham Lincoln, “My Childhood-Home I See Again” (excerpt)

Leroi Jones, “Bang, bang, outishly” (excerpt)

Hettie Jones, “Ode to My Kitchen Sink”

Brenda Coultas, “A Handmade Museum” (excerpt)

ee cummings, ”i was sitting in mcsorley’s…”

Related Content:

Rare Footage of Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac & Other Beats Hanging Out in the East Village (1959)

Hear Allen Ginsberg Teach “Literary History of the Beats”: Audio Lectures from His 1977 & 1981 Naropa Courses

Iggy Pop Conducts a Tour of New York’s Lower East Side, Circa 1993

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Her play Zamboni Godot is opening in New York City in March 2017. Follow her @AyunHalliday.