The vicious, vitriolic imagery and rhetoric of this election season can seem overwhelming, but as even casual students of history will know, it isn’t anything new. Each time historic social change occurs, reactionary counter-movements resort to threats, appeals to fear, and demeaning caricatures—whether it’s anti-Reconstruction propaganda of the 19th century, anti-Civil Rights campaigns 100 years later, or anti-LGBT rights efforts today.

At the turn of the century, the women’s suffrage movement faced significant levels of abuse and resistance. One photograph has circulated, for example, of a suffrage activist lying in the street as police beat her. (The woman in the photo is not Susan B. Anthony, as many claim, but a British suffragist named Ada Wright, beaten on “Black Friday” in 1910.) It’s an arresting image that captures just how violently men of the day fought against the movement for women’s suffrage. [It’s also worth noting, as many have: the early suffrage movement campaigned only for white women’s right to vote, and sometimes actively resisted civil rights for African-Americans.]

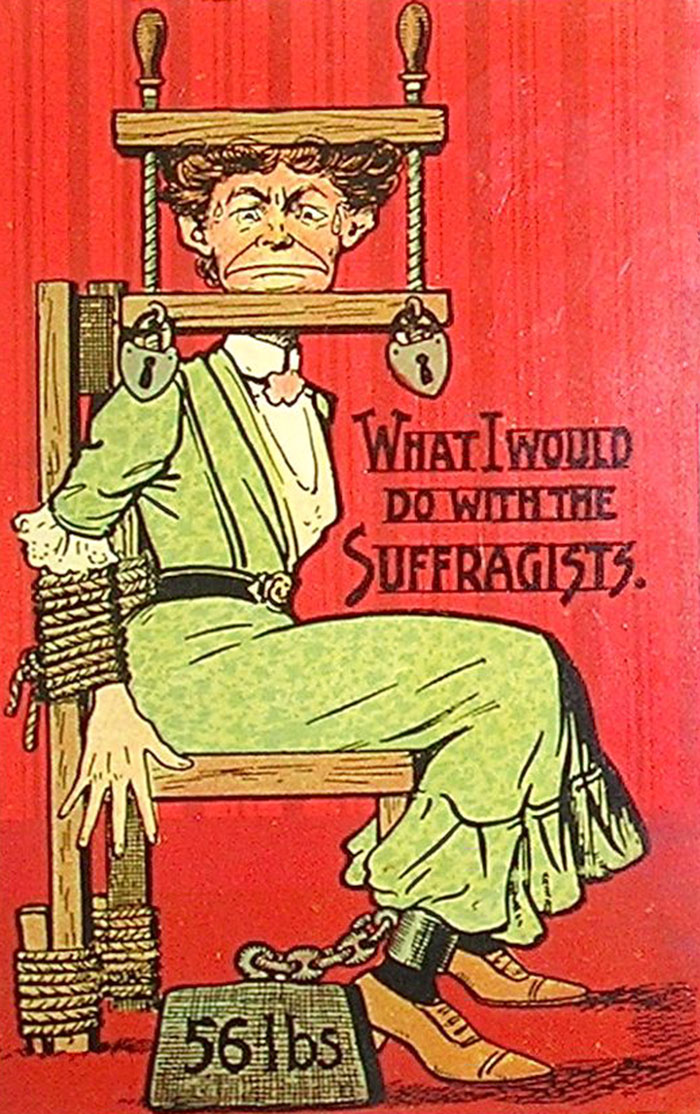

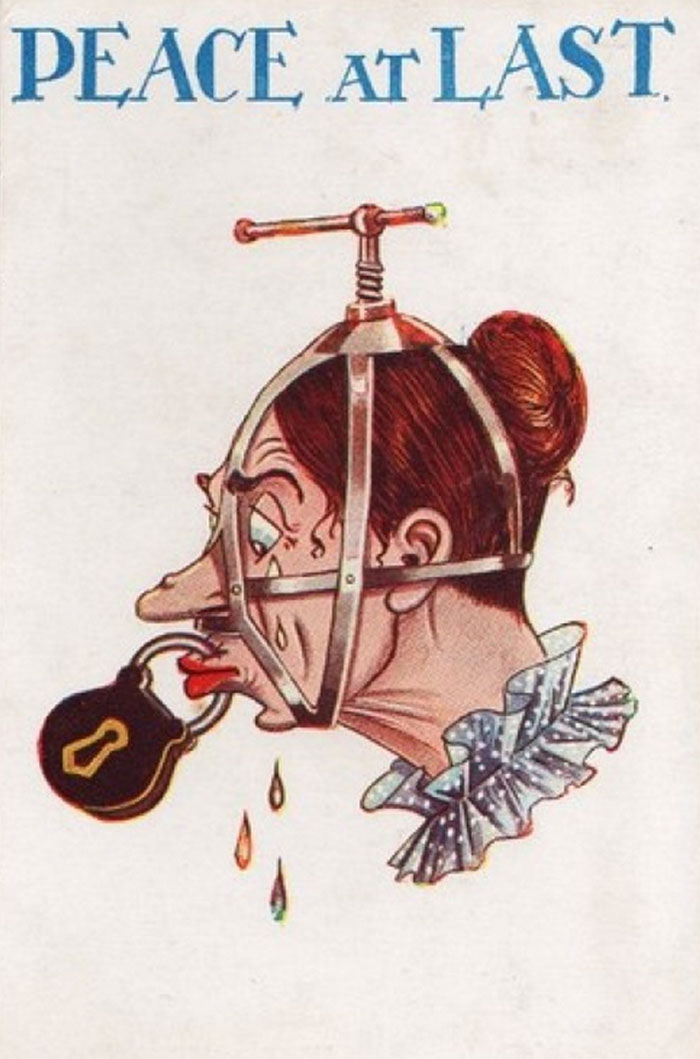

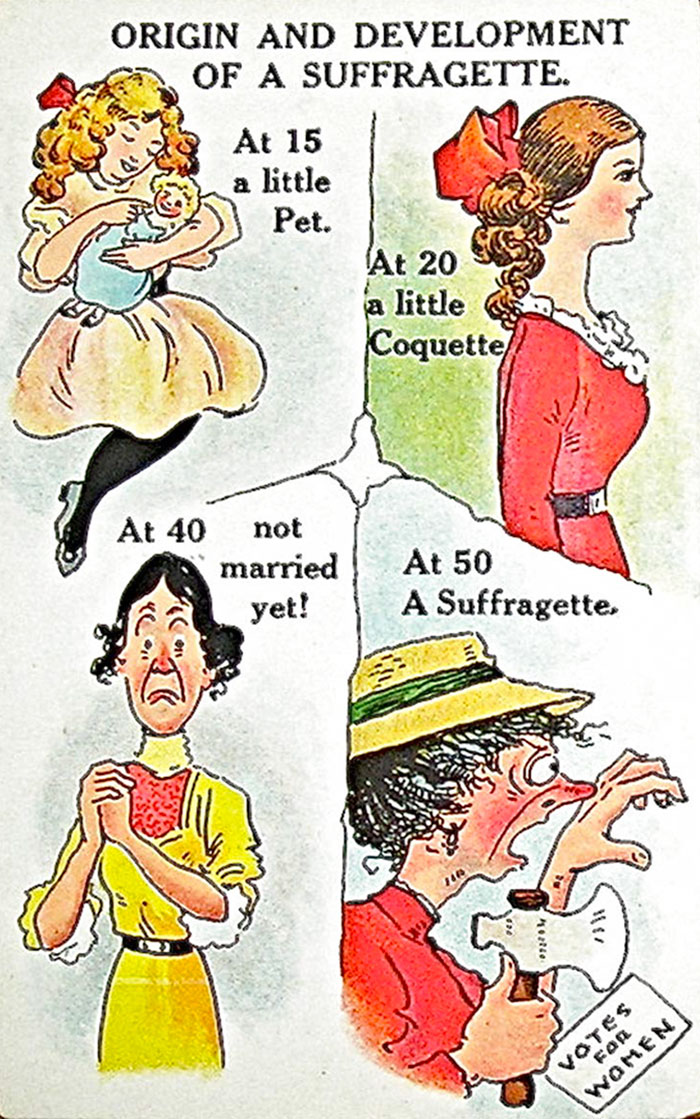

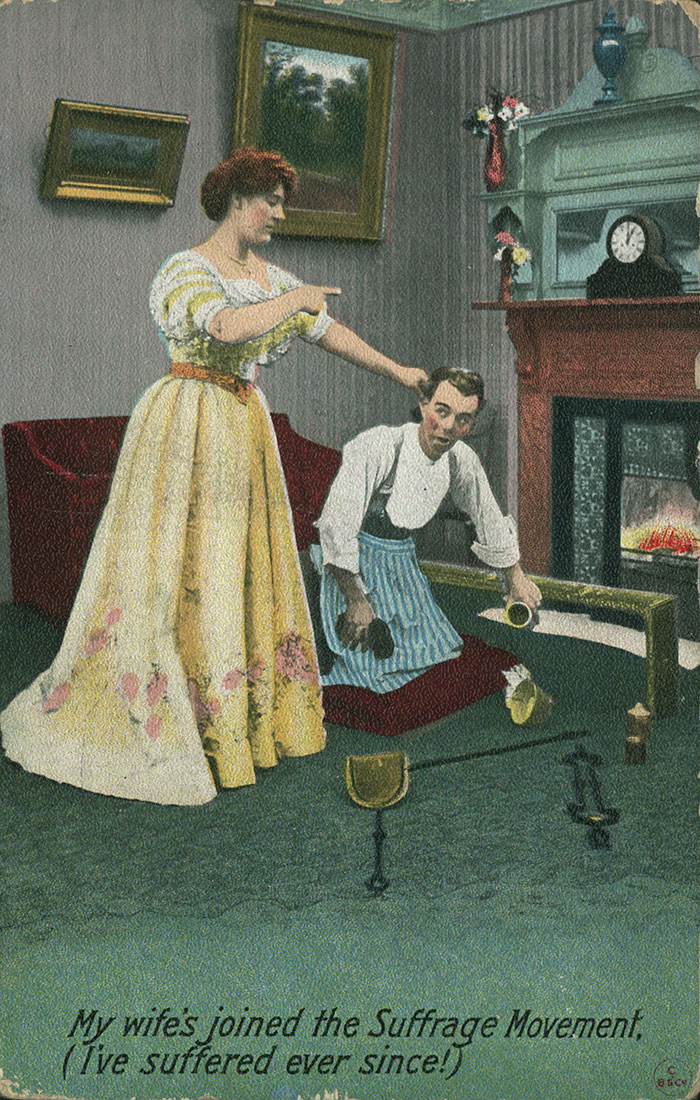

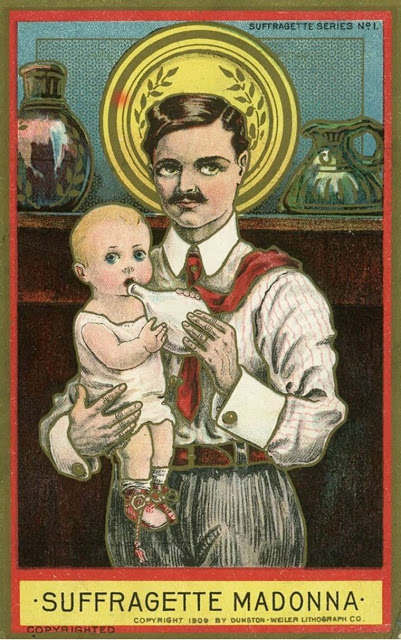

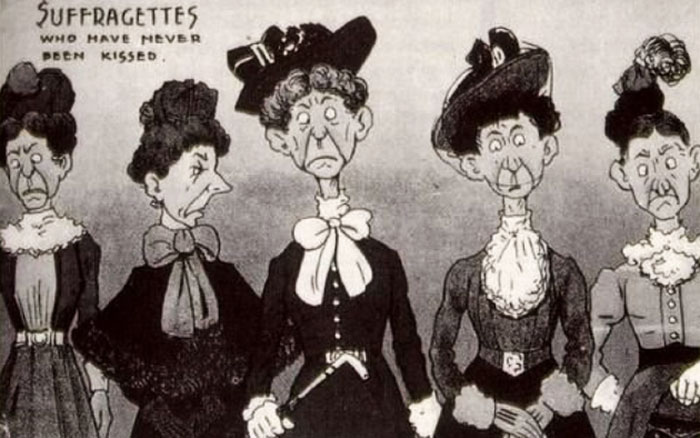

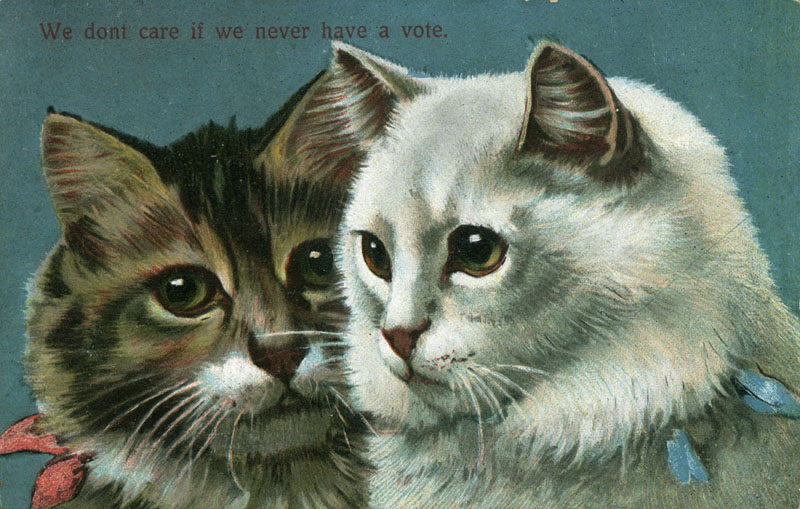

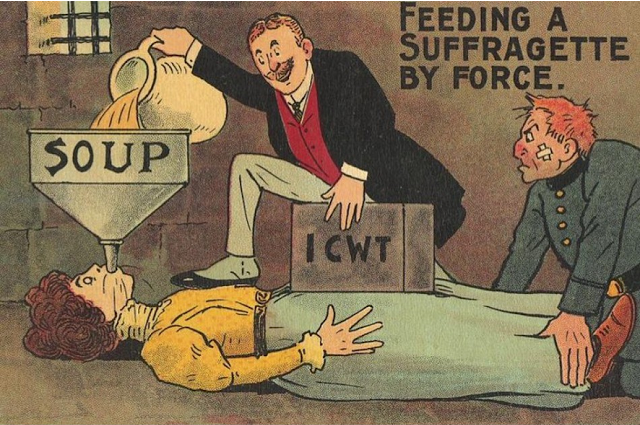

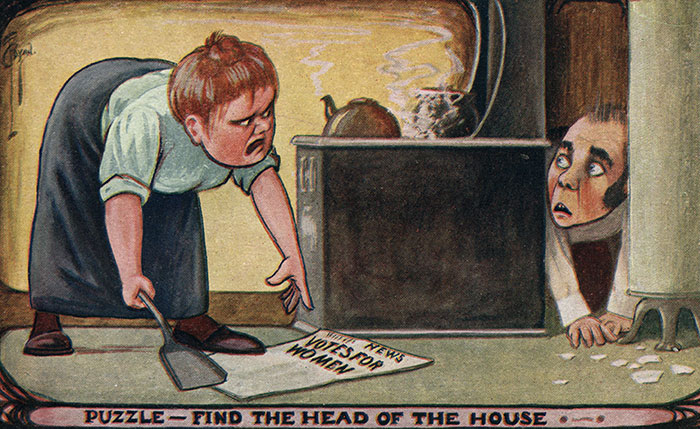

As you can see from the sample anti-suffrage postcards here—dating from the late 19th to early 20th centuries— propaganda against the women’s vote tended to fall into three broad categories: Disturbingly violent wish-fulfillment involving torture and physical silencing; characterizations of suffragists as angry, bitter old maids, hatchet-wielding harridans, or domineering, shrewish wives and neglectful mothers; and, correspondingly, depictions of neglected children, and husbands portrayed as saintly victims, emasculated by threats to traditional gender roles, and menaced by the suggestion that they may have to care for their children for even one day out of the year!

These postcards come from the collection of Catherine Palczewski, professor of women’s and gender studies at the University of Northern Iowa. She has been collecting these images, from both the U.S. and Britain, for 15 years. On her website, Palczewski quotes George Miller’s comment that postcards like these “offer a vivid chronicle of American political values and tastes.” Palczewski describes these particular images as “a fascinating intersection [that] occurred between advocacy for and against woman suffrage, images of women (and men), and postcards. Best estimates are that approximately 4,500 postcards were produced with a suffrage theme.”

As she notes in the quote above, the postcards printed during this period did not all oppose women’s suffrage. “Suffrage advocates,” writes Palczewski, “recognized the utility of the postcard as a propaganda device” as well. Pro-suffrage postcards tended to serve a documentary purpose, with “real-photo images of the suffrage parades, verbal messages identifying the states that had approved suffrage, or quotations in support of extending the vote to women.” For all their attempts at presenting a serious, informative counterweight to incendiary anti-suffrage images like those you see here, suffrage activists often found that they could not control the narrative.

As Lisa Tickner writes in The Spectacle of Women: Imagery of the Suffrage Campaign 1907–1914, postcard producers without a clear agenda often used photos and illustrations of suffragists to represent “topical or humorous types” and “almost incidentally” undercut advocates’ attempts to present their cause in a newsworthy light. The image of the suffragette as a trivial figure of fun persisted into the mid-twentieth century (as we see in Glynis Johns’ comically neglectful Winifred Banks in Walt Disney’s 1964 Mary Poppins adaptation).

Palczewski’s site offers a brief history of the “Golden Age” (1893–1918) of political postcards and organizes the collection into categories. One variety we might find particularly charming for its use of cats and kittens actually has a pretty sinister origin in the so-called “Cat-and-Mouse Act” in the UK. Jailed suffragists had begun to stage hunger strikes, and journalists provoked public outcry by portraying force-feeding by the government as a form of torture. Instead, striking activists were released when they became weak. “If a woman died after being released,” Palczewski explains, “then the government could claim it was not to blame.” When a freed activist regained her strength, she would be rearrested. “On November 29, 1917,” Palczewski writes, “the US government announced it plans to use Britain’s cat and mouse approach.”

You can see many more historical pro- and anti-suffrage postcards at Palczewski’s website, and you are free to use them for non-commercial purposes provided you attribute the source. You are also free, of course, to draw your own comparisons to today’s hyperbolic and often violently misogynist propaganda campaigns.

Related Content:

Download All 239 Issues of Landmark UK Feminist Magazine Spare Rib Free Online

11 Essential Feminist Books: A New Reading List by The New York Public Library

Download Images From Rad American Women A‑Z: A New Picture Book on the History of Feminism

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness