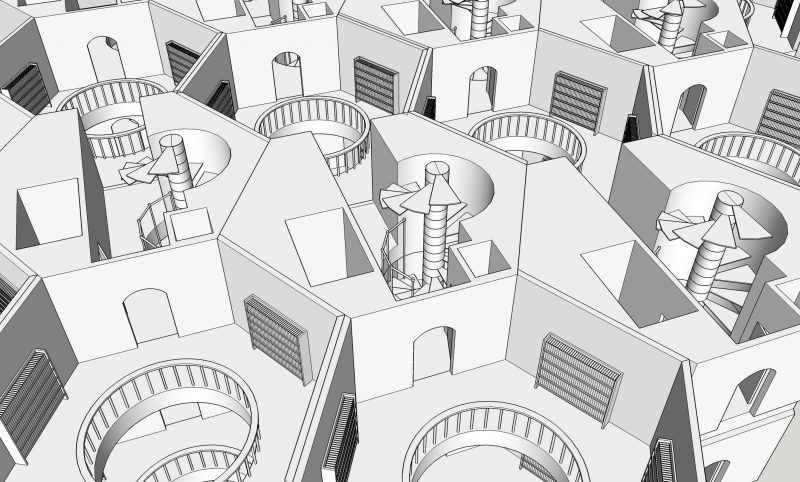

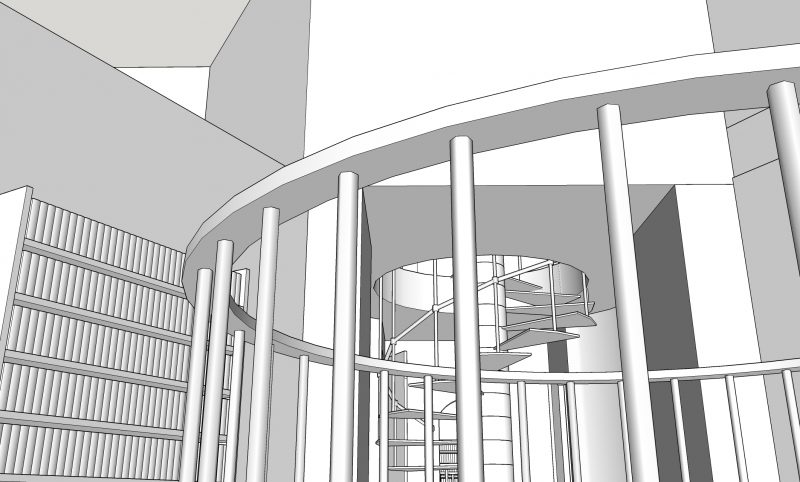

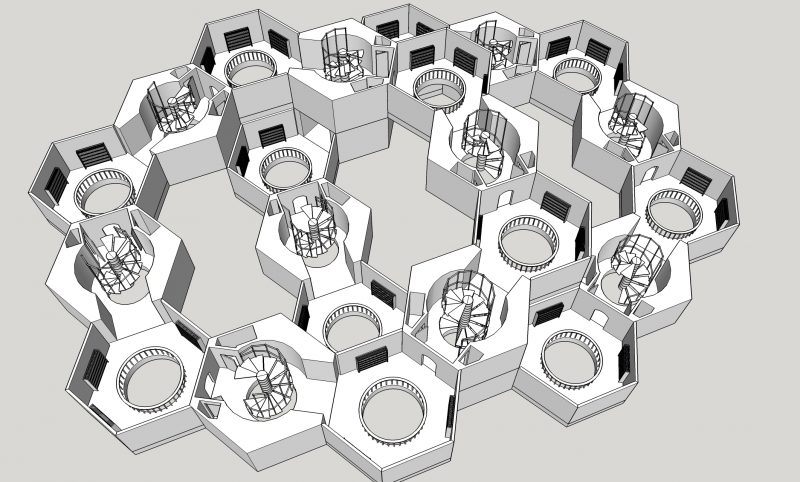

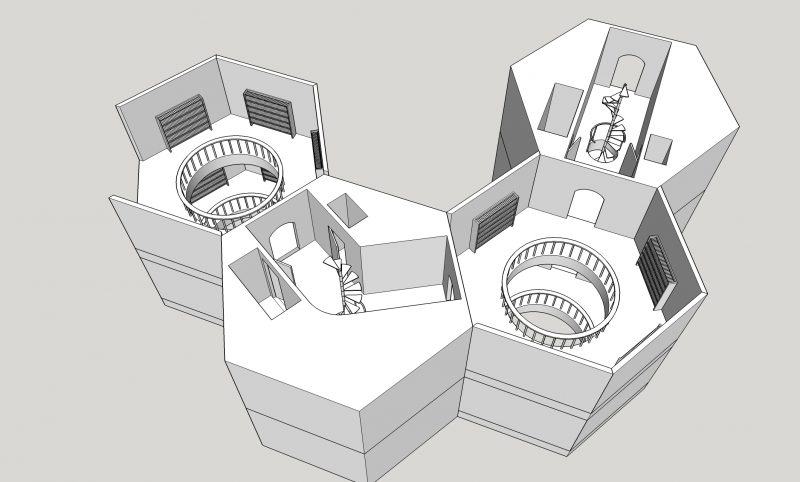

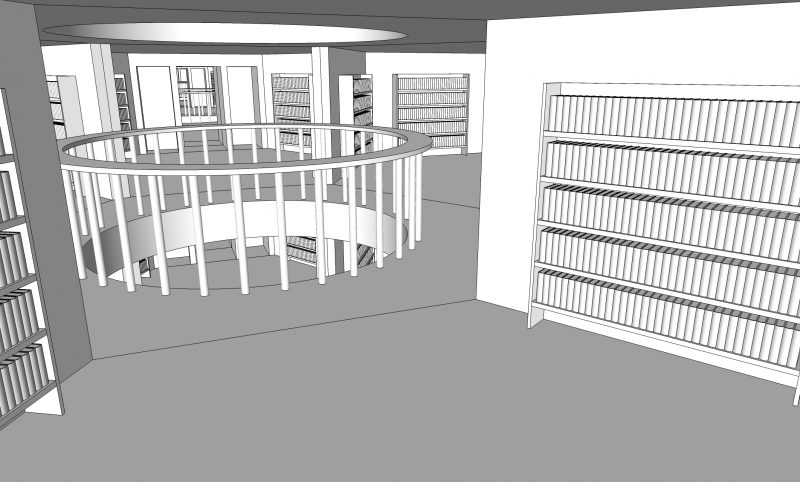

Sketchup renderings of the Library of Babel. Images courtesy of Jamie Zawinski.

Fulfilling the maxim “write what you know,” Argentine fabulist Jorge Luis Borges penned one of his most extraordinary and bewildering stories, “The Library of Babel,” while employed as an assistant librarian. Borges, it has been noted—by Borges himself in his 1970 New Yorker essay “Autobiographical Notes”—found the work dreary and unfulfilling: “nine years of solid unhappiness,” as he put it plainly. “Sometimes in the evening, as I walked the ten blocks to the tramline, my eyes would be filled with tears.”

And yet, for all of its tedium, his library position suited his needs as a writer like none other could. “I would do all my library work in the first hour,” he remembers, “and then steal away to the basement and pass the other five hours in reading or writing.” During those stolen hours, Borges dreamed up a library the size of the universe, “composed of an indefinite and perhaps infinite number of hexagonal galleries, with vast air shafts between, surrounded by very low railings.” Like so many of the objects and places in Borges’ stories, this fantastic structure, Escher-like, is both vividly described and impossible to imagine.

Many have tried their hand at visually rendering the Library of Babel, but according to programmer Jamie Zawinski, “past attempts,” writes Carey Dunne at Hyperallergic, “aren’t faithful to the text,” omitting crucial structures like the “sleep chamber, lavatory, and hallway” and screwing up “the placement of the spiral stairway.” You can see Zawinski’s various critiques of these supposed failures on his blog, JWZ. And you may wonder how it’s even possible to construct an accurate model of a structure that may have no finite boundaries and whose internal architecture the story itself calls into question. Nonetheless, Zawinski has boldly given it a try.

Using the 3D modeling program Sketchup, he has designed what he believes to be a model superior to the rest, though he admits “I don’t think this is quite right either.” If you’re wondering “Why is he doing this?” Zawinski writes, “you and I have that in common.” The Borgesian task, like that of the librarian, is an endless one, pursued with scholastic rigor for its own sake rather than for some great reward. And once one enters the labyrinth of his twisting designs, there may be no way out but eternally through. “The possibility of a man’s finding his Vindication,” writes Borges wearily of certain librarians’ attempts to solve the library’s riddles, “or some treacherous variation thereof, can be computed as zero.”

So Zawinski trudges on. His “wrestling with the details of his rendering,” writes Dunne, “his obsessive analysis of the wording of Borges’ description, recalls the library inhabitants’ futile quests to decipher the mysteries of the library.” The programmer’s admirable attention to the physics of the space may at times sound like a rather leaden way to approach what is essentially an elaborate metaphor: “I can’t help but think about the weight and pressure of a column of air that high,” he muses in his initial explorations, “and what is it sitting on, and how to route the plumbing from all of those toilets, and that toilets imply digestion, so where does the food come from?”

Such questions take him far afield of Borges’ theo-philosophical parable: “Is there a section of the library devoted to farming, and metallurgy?” Nonetheless, Zawinski’s detailed analysis has produced a visualization of the space like none other, and he admits to “overthinking a sub-infinite but nearly boundless hill of beans.” Borges’ imaginary librarian has abandoned trying to solve the library’s mysteries. Humbled by the failures of those who came before him, he persists in the “elegant hope” that the library “is unlimited and cyclical… repeated in the same disorder… which, thus repeated, would be an order: the Order.” He wisely leaves the ultimate metaphysical discovery, however, to “an eternal traveler” with infinite time on their hands.

You can view Zawinski’s commentary here, and see his designs here. On the bottom of this page, he lets you download his Sketchup file.

via Hyperallergic

Related Content:

Jorge Luis Borges Selects 74 Books for Your Personal Library

Jorge Luis Borges’ Favorite Short Stories (Read 7 Free Online)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness