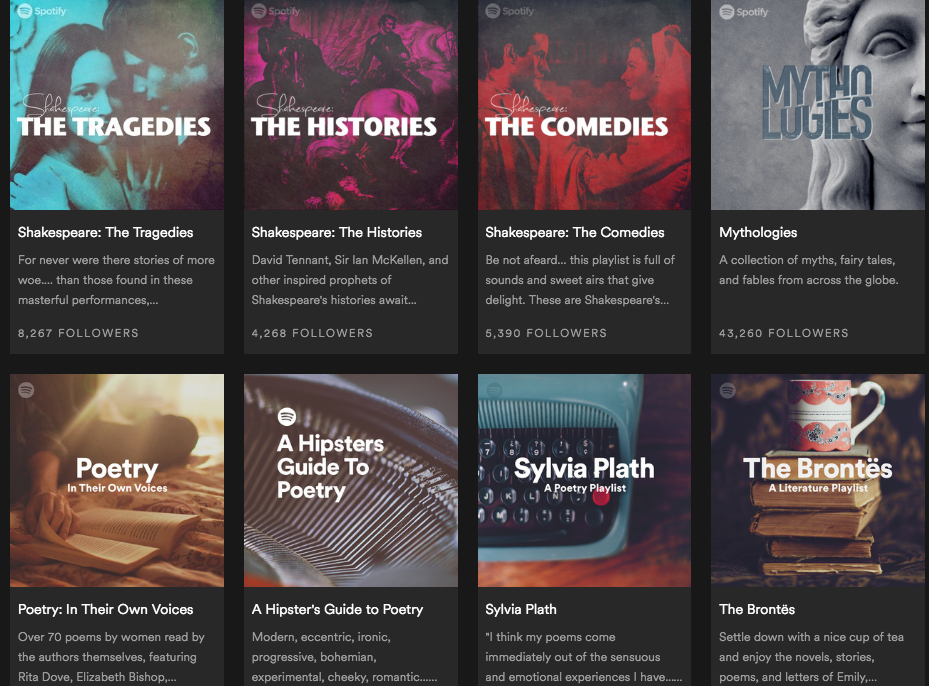

Here’s a little known tip. If you open Spotify, click “Browse” (in the left hand nav), then scroll way down to “Word,” you will find a number of free audiobook collections–readings by Sylvia Plath, Langston Hughes, and Dylan Thomas; old time crime and sci-fi dramas; a big H.P. Lovecraft compendium and more. But that way of navigating things really only scratches the surface of what Spotify has to offer.

If you rummage around enough, you’ll find many quality recordings–everything from Christopher Lee reading Dracula and Frankenstein, to Kurt Vonnegut reading four of his novels, to a 68-hour playlist of Shakespeare’s plays being performed by legendary actors. We’ve found 75+ recordings in recent months and gradually added them to our collection, 1,000 Free Audio Books: Download Great Books for Free. But they seemed worth highlighting and calling to your attention here.

If you need Spotify’s free software, download it here. And if you find any other gems, please list them in the comments below and we’ll add them to our list.

- Austen, Jane — Pride and Prejudice — Spotify

- Beckett, Samuel – Waiting for Godot (Theatrical performance with Bert Lahr) – Spotify

- Bukowski, Charles – 4 Hours of Bukowski Readings – Spotify

- Bukowski, Charles – Hostage – Spotify

- Bukowski, Charles – Master Collection – Spotify

- Burroughs, William S. – Call Me Burroughs (his first spoken word album) – Spotify

- Burroughs, William S. – Let Me Hang You (posthumous album settting readings of Naked Lunch to music) – Spotify

- Carroll, Lewis – Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (Read by Sir John Gielgud) – Spotify

- Carroll, Lewis – Through the Looking Glass (Read by Joan Greenwood, Stanley Holloway) – Spotify

- Ciardi, John – As If: Poems New and Selected by John Ciardi (read by the author) –Spotify

- Coleridge, Samuel – Poems (Read by Ralph Richardson) – Free Spotify

- Collins, Billy – The Best Cigarette (Poetry collection read by the author) – Free Spotify

- Collins, Billy – Soap – Spotify

- Conan Doyle, Arthur – The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes (64 Hours of Readings) – Spotify

- Dante Alighieri – The Inferno, Cantos I‑VIII (Read by John Ciardi) – Spotify

- Defoe, Daniel – Robinson Crusoe (Read by Nigel Graham)

- Dickinson, Emily – Poems & Letters – Spotify

- Eliot, T.S. – The Cocktail Party (Performed by Alec Guinness & Cathleen Nesbitt) – Free Spotify

- Eliot, T.S. – Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats (Read by T.S. Eliot) – Spotify playlist

- Eliot, T.S. – T.S. Eliot Reading Poems and Choruses – Spotify

- Eliot T.S. — T.S. Eliot Reads the Waste Land — Spotify

- Ferlinghetti, Lawrence – A Coney Island of the Mind – Spotify

- Frost, Robert – Robert Frost Reads His Poetry – Free Spotify

- Ginsberg, Allen — Howl — Spotify

- Ginsberg, Allen – First Blues: Rags, Ballads and Harmonium Songs – Spotify

- Ginsberg, Allen – The Last Word on First Blues – Spotify

- Ginsberg, Allen – The Lion for Real – Free on Spotify

- Ginsberg, Allen – Witchita Vortex Sutra – Spotify

- Hawthorne, Nathaniel – The Scarlet Letter – Spotify

- Hugo, Victor – The Hunchback of Notre Dame (Abridged version read by Christopher Lee) – Spotify

- Hesse, Hermann – Siddhartha – Spotify

- Hitchcock, Alfred – Alfred Hitchcock Presents Ghost Stories for Young People – Spotify

- Hughes, Langston – Langston Hughes Reads Langston Hughes – Spotify

- Hughes, Langston – The Dream Keeper and Other Poems of Langston Hughes (Read by Hughes) – Spotify

- Hughes, Langston – The Glory of Negro History – Spotify

- Hughes, Langston – The Voice of Langston Hughes – Spotify

- Joyce, James – Dubliners – Free on Spotify

- Joyce, James – “The Dead” (Read by Bart Wolffe) – Spotify

- Kafka, Franz – The Metamorphosis – Spotify

- Kerouac, Jack – 4 Albums with Kerouac Reciting Poetry & Verse – Spotify

- Leroux, Gaston – The Phantom of the Opera (Abridged version read by Christopher Lee) – Spotify

- Lovecraft, H.P – The Call of of Cthulhu & Other Stories – Spotify

- Melville, Herman – Moby-Dick (Abridged version read by Hayward Morse) – Spotify

- Miller, Arthur – Readings from The Crucible and Death of a Salesman – Spotify

- Nabokov, Vladimir – Vladimir Nabokov Reads from Lolita & Selected Poems – Spotify

- Nash, Ogden – Christmas with Ogden Nash – Spotify

- Nash, Ogden – Ogden Nash Reads Ogden Nash – Spotify

- Neruda, Pablo – Pablo Neruda Lee a Pablo Neruda (in Spanish) – Spotify

- Orwell, George – Animal Farm – Spotify

- Poe, Edgar Allan – The Essential Edgar Allan Poe – Spotify

- Poe, Edgar Allan – The Mask of the Red Death (Read by William S. Burroughs) –Spotify

- Prokofiev, Sergei – Peter and the Wolf (Narrated by David Bowie) – Spotify

- Sandburg, Carl – A Lincoln Album: Readings by Carl Sandurg – Spotify

- Sandburg, Carl – The People Yes – Spotify

- Sexton, Anne – What’s That – Spotify

- Schiller, Friedrich – Poetry of Friedrich von Schiller: Read in German by Kinski –Spotify

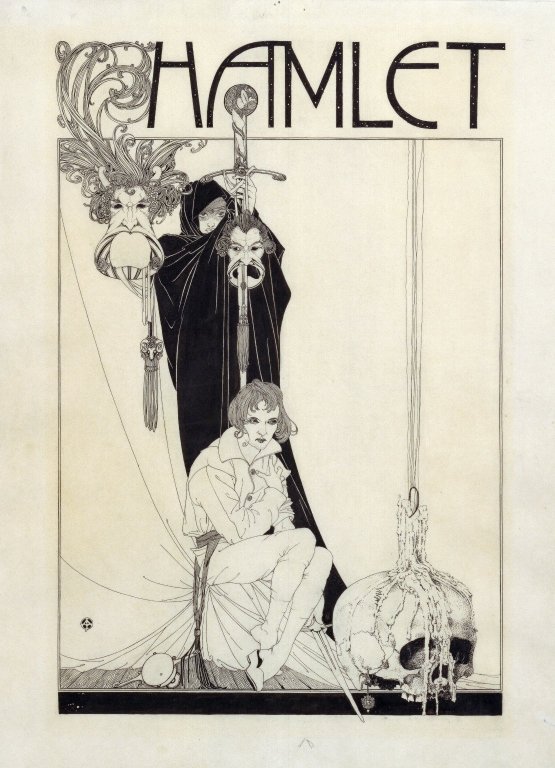

- Shakespeare, William – A 68 Hour Playlist of Shakespeare’s Plays Being Performed by Great Actors: Gielgud, McKellen & More – Free on Spotify

- Shakespeare, William – Hamlet (French translation by Marcel Pagnol) – Spotify –YouTube

- Shakespeare, William – Hamlet (Starring John Gielgud) – Spotify + Archive.org

- Shakespeare, William – Macbeth (with Alec Guinness) – Free Spotify

- Shelley, Mary – Frankenstein (Abridged version read by Christophe Lee) – Spotify

- Shelley, Percy Bysshe – Various Poems (Read by Vincent Price) – Free Spotify

- Steinbeck, John – “The Snake” and “Johnny Bear” – Free Stream – Spotify

- Stevenson, Robert Louis – The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll & Mr Hyde (Read by Christopher Lee) – Spotify

- Stevenson, Robert Louis – Treasure Island (Read by Hans Conried) – Spotify

- Stoker, Bram – Dracula (Read by Christopher Lee) – Spotify

- Thomas, Dylan – Dylan Thomas Reads 8 Hours of His Poetry – Spotify

- Thomas, Dylan – An Evening with Dylan Thomas – Spotify

- Thomas, Dylan – Richard Burton Reads 15 Poems by Dylan Thomas – Spotify

- Twain, Mark – The Adventures of Tom Sawyer – Spotify version

- Vonnegut, Kurt – Slaughterhouse 5, Cat’s Cradle, Breakfast of Champions, Welcome to the Monkey House (Abridged readings by Vonnegut) – Spotify

- Welles, Orson — 61 Hours of Orson Welles’ Classic 1930s Radio Plays: War of the Worlds, Heart of Darkness & More — Spotify

- Wells, HG – The War of the Worlds (Read by Maxwell Caulfield) – Spotify

- Wilde, Oscar – The Importance of Being Earnest (Performed by John Gielgud) – Free

- Woolf, Virginia – The Short Stories – Spotify

- Yeats, William Butler – William Butler Reads His Own Work – Spotify

Looking for free, professionally-read audio books from Audible.com? Here’s a great, no-strings-attached deal. If you start a 30 day free trial with Audible.com, you can download two free audio books of your choice. Get more details on the offer here.

Related Content:

1,000 Free Audio Books: Download Great Books for Free

Free Online Literature Courses

Download Two Harry Potter Audio Books for Free (and Get the Rest of the Series for Cheap)