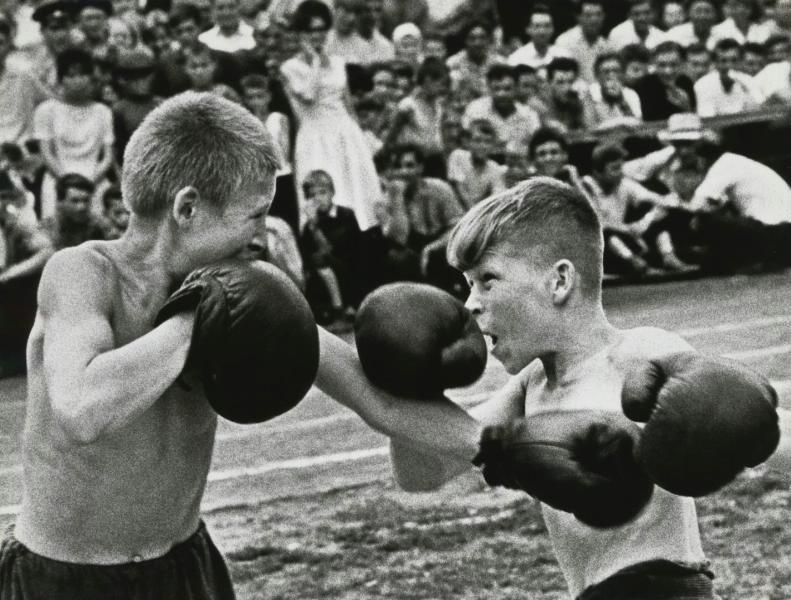

Tall and dashing, with the face of a boxer and glowering stare of a gangster, Russian Futurist poet, painter, director, and actor Vladimir Mayakovsky (1893–1930) came by his intimidating look honestly. As a teenage activist, he carried an unlicensed gun, freed female political prisoners, and “was dismissed from grammar school,” shortly after joining the Social Democratic Labor Party in 1908; “He spent much of the next two years in prison,” writes the Academy of American Poets, “due to his political activities.” A committed Bolshevik throughout his career, Mayakovsky celebrated the Revolution with poems and plays and devoted his talents to the Party, becoming a rare example of an avant-garde artist who makes populist art.

In many ways, Mayakovsky’s career seems representative, even exemplary, of the Futurist movement. Uncritically adopting Communist doctrine and embracing wholesale innovation, these artists fell victim to the same forces, as Socialist Realism increasingly became the official Soviet style and the rigid, bland arbiter of Party taste.

In 1912, Mayakovsky signed a manifesto with other Futurists “A Slap in the Face of Public Taste,” proposing, among other things, to “throw Pushkin, Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, etc., etc. overboard from the Ship of Modernity.” Of other popular writers of the time, including Maxim Gorky and Ivan Bunin, the Futurists declared, “From the heights of skycrapers we gaze at their insignificance!…”

By 1918, Mayakovsky was a star. That year, he made three films, “for each of which he authored the scenario,” writes biographer Edward James Brown, “and played the principal part.” Two of the films have disappeared, the third, The Young Lady and the Hooligan, you can watch above. “A story of hopeless love,” the film stars Mayakovsky as the titular hooligan who falls for a new schoolmistress “sent into the slums to teach adult classes.” The hooligan enrolls and changes his ways, but is then killed tragically in a fight. Spoiler alert: “Before dying he begs his mother to have the teacher come to him. She comes, she kisses him on the lips, and he dies.”

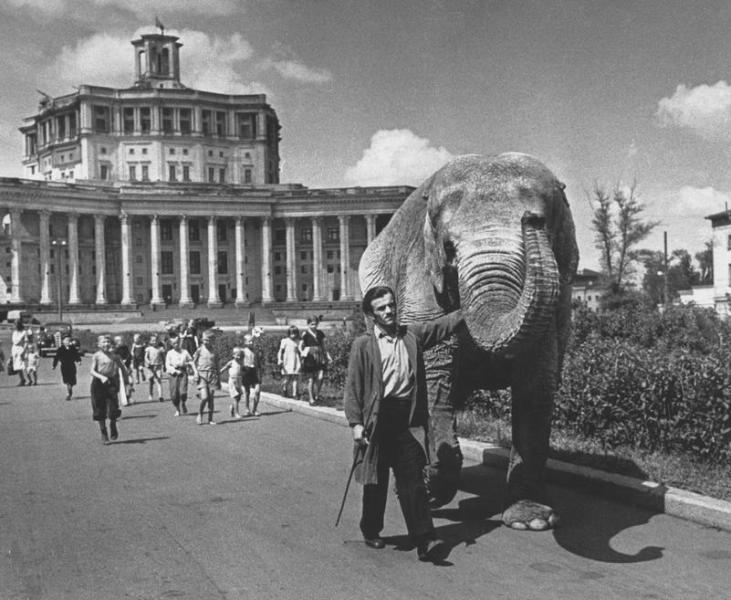

The silent film, based on an 1885 Italian play called The Workers’ Young Schoolmistress, seems to have little to do with Soviet dogma, and yet it received tremendous acclaim, and became an instrument of propaganda, shown in mass screenings in Moscow and Leningrad on May Day of 1919. Film scholar Marina Burke suggests some of the reasons for its popularity: “many of the scenes are shot outdoors, and the film is rich in naturalistic details of current Soviet conditions”— the realist depiction of workers’ lives resonated widely with real-life workers. And yet, Mayakovsky’s film also displays those characteristics that make him a distinctly un-Soviet artist and would sometimes put him at odds with the State’s overbearing dogmatism.

Mayakovsky plays the hooligan in a “disconcertingly modern, disaffected-young-man style” that reminds critic Malcolm Le Grice of “a kind of precursor to Rebel Without a Cause, with Mayakovsky as a slightly improbable James Dean.” The poet was too much an individual to play an idealized everyman. Each of the protagonists in his three film draw from life—three versions of the artist who wrote critical poems like “A Talk with a Tax Collector” and satirical plays that made the State uneasy, even as he extolled its virtues at public events.

Mayakovsky would also not make strictly realist art, having disavowed its “filthy stigmas” the year previous in his Futurist Manifesto. The naturalist scenes in The Young Lady and the Hooligan “are interspersed,” writes Burke, “with flights of fancy that are almost surrealist in tone,” such as the schoolteacher menaced by dancing letters. Despite its conventional, sentimental plot and structure, Mayakovsky’s only surviving film presents us with a complicated, ambivalent work, almost “a parody of romantic fiction films,” and—like all of his work—the swaggering expression of a thoroughly individual artist.

The Young Lady and the Hooligan will be added to our collection of Silent Films, a subset of our meta list 4,000+ Free Movies Online: Great Classics, Indies, Noir, Westerns, Documentaries & More.

Related Content:

Hear Russian Futurist Vladimir Mayakovsky Read His Strange & Visceral Poetry

Three Essential Dadaist Films: Groundbreaking Works by Hans Richter, Man Ray & Marcel Duchamp

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness