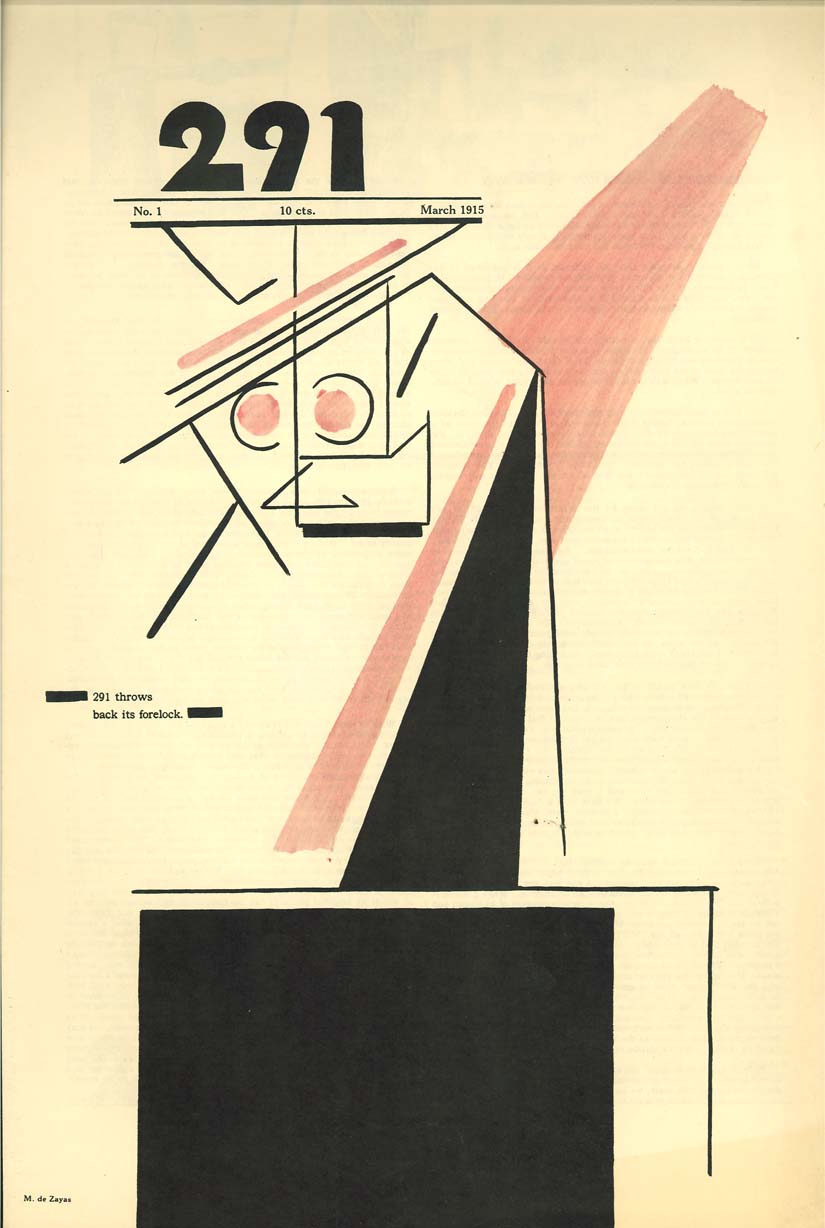

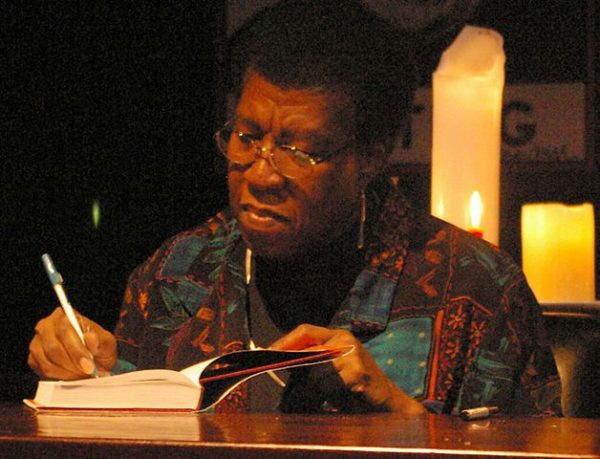

Image by Nikolas Coukouma, via Wikimedia Commons

The Internet has been abuzz and atwitter these past few months with stories about prophetic predictions of the rise of Trump, buried in ancient texts like Back to the Future II, and an episode of The Simpsons from 2000. Then there’s Mike Judge’s now ten-year-old satire Idiocracy. While not specifically modeled after a Trump presidency, its depiction of the country as a violent, backward dystopia, armed and corporate-branded to the teeth, sure does resemble the kind of place many imagine Trump and his supporters might build. These allusions and direct references don’t necessarily provide evidence of the writers’ clairvoyance; after all, Trump has threatened us with his candidacy since 1988, with mostly unserious statements. But they do show us that we’ve seen this version of the future coming for the last thirty years or so.

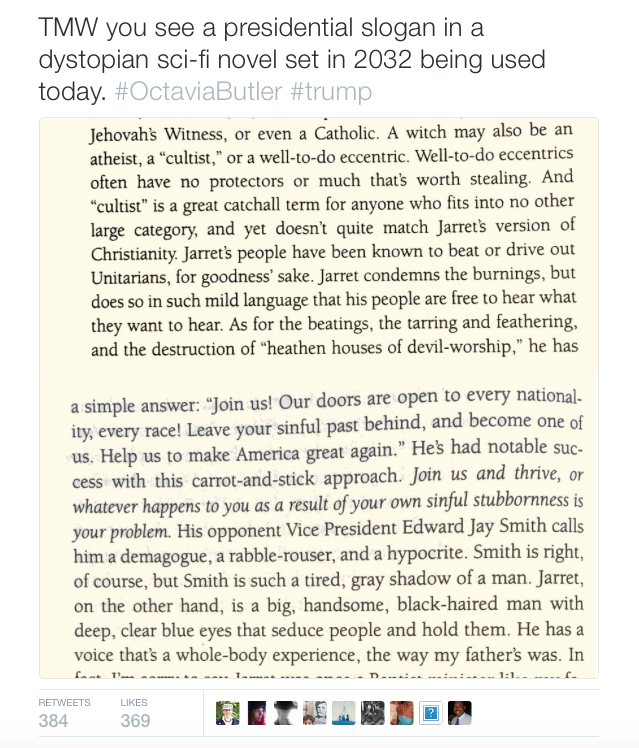

One prediction you may have missed, however, offers us a much more sober take on the rise of a frightening neo-fascist during a time of fear and civil unrest. As Twitter user @oligopistos pointed out, in the second book of her Earthseed series, The Parable of the Talents (1998), Hugo and Nebula-award winning science fiction writer Octavia Butler gave us Senator Andrew Steele Jarret, a violent autocrat in the year 2032 whose “supporters have been known… to form mobs.” Jarret’s political opponent, Vice President Edward Jay Smith, “calls him a demagogue, a rabble-rouser, and a hypocrite,” and—most presciently—Jarret rallies his crowds with the call to “make America great again.”

Though Trump has trademarked it, the slogan did not originate with him, nor even with Butler’s Jarret character—the 1980 Reagan-Bush campaign used it, as Matt Taibbi pointed out Rolling Stone last year. (Historians have even shown that another of Trump’s slogans, “America First,” was used by Charles Lindbergh and “Nazi-friendly Americans in the 1930s.”) Again, proto-Trumpism has been in the zeitgeist for a long time. While Butler may have used “Make American Great Again” from her memory of Reagan’s first campaign, the way her character employs it speaks to our moment for a number of reasons.

It’s true that Senator Jarret differs from Trump in some significant ways: “Jarret’s beef is with Canada instead of Mexico,” writes Fusion, and “instead of business acumen as his main credential, religion is Jarret’s stump. He’s the head of a group called Christian America, which is intolerant of other religious views, and whose supporters burn ‘witches’—meaning Muslims, Jews, Hindus and Buddhists—at the stake.” Our current candidate may have co-opted the religious right, but he doesn’t speak their language at all. Nonetheless, he has made promises that give secularists and non-Christians chills, and religious intolerance has formed the backbone of his campaign and of the rhetoric that has driven his party to the far right.

Jarret and the fanaticism he inspires become central the novel’s story, but the crucial background in Butler’s 1998 depiction of a post-apocalyptic 2032 are the conditions she identifies as giving rise to the Senator’s rule (and which she described in the first book, Parable of the Sower). In Talents, the narrator’s father Taylor Franklin Bankole writes,

I have read that the period of upheaval that journalists have begun to refer to as “the Apocalypse” or more commonly, more bitterly, “the Pox” lasted from 2015 through 2030—a decade and a half of chaos…. I have also read that the Pox was caused by accidentally coinciding climatic, economic, and sociological crises. It would be more honest to say that the Pox was caused by our own refusal to deal with obvious problems in those areas. We caused the problems: then we sat and watched as they grew into crises.

In Butler’s fiction, the rise of Senator Jarret and his mobs is an outcome of the same kinds of impending crises we face now, and that far too many of our leaders dutifully ignore as they stage increasingly acrimonious and bizarre forms of political theater. Butler’s indirect warning to us in Parable of the Talents may be less about the demagogic leader and his cult—though they pose the most dire existential threat in the book—than about the causes and conditions that created “the Pox,” the kind of social collapse that Kurt Vonnegut warned of ten years before Butler in his time-capsule letter to the people of 2088, vaguely identifying similar kinds of “climatic, economic, and sociological” crises to come. Would that we could abandon empty spectacle and heed these Cassandras of the near future.

Related Content:

In 1988, Kurt Vonnegut Writes a Letter to People Living in 2088, Giving 7 Pieces of Advice

Isaac Asimov Predicts in 1964 What the World Will Look Like Today

Noam Chomsky on Whether the Rise of Trump Resembles the Rise of Fascism in 1930s Germany

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness