Nearly every Western youth subculture in existence eventually gets its own Hollywood film. Like most such films, 1993’s Swing Kids—which tells the story of jazz-loving German youth during the rise of the Third Reich—managed to be both inaccurate and critically reviled. Roger Ebert hated the film’s celebration of “a very small footnote to a very large historical event,” and compared the Swing Kids to “Nero, who fiddled while Rome burned.” Ebert’s reaction is uncharacteristic of him; he writes critically of the film, but he also seemed to find its subject—the kids themselves—repellant.

The review prompts us to ask: Were these kids—dubbed Swingjugend by the Nazis—participating in a revolutionary act of cultural resistance, or were they no more than typical, naive teenagers who preferred to “listen to big bands than enlist in the military”? (After all, writes Ebert, “who wouldn’t?”) But the question about the Swing Kids’ political motivations may be less relevant than one about whether their pursuit of a carefree, jazz-scored lifestyle under Nazism constitutes a “small footnote” in history. Should we know and care about the Swing Kids, and if so, why?

A German site called Swingstyle compiles information about the subculture and admits that “the real Swing Kids were politically unsophisticated.” Despite being seen as a “youth problem” by Nazi authorities, they “actually cared little for contesting official policies toward Jews or other matters. They just wanted to have fun at a dark time in their country’s history, and avoid the war if possible.” Or, rather, most of them wanted to avoid joining the Hitler Youth, mandated for all young people in 1939: “We must remember the age of most swing kids was between 12 and 16 or 17.”

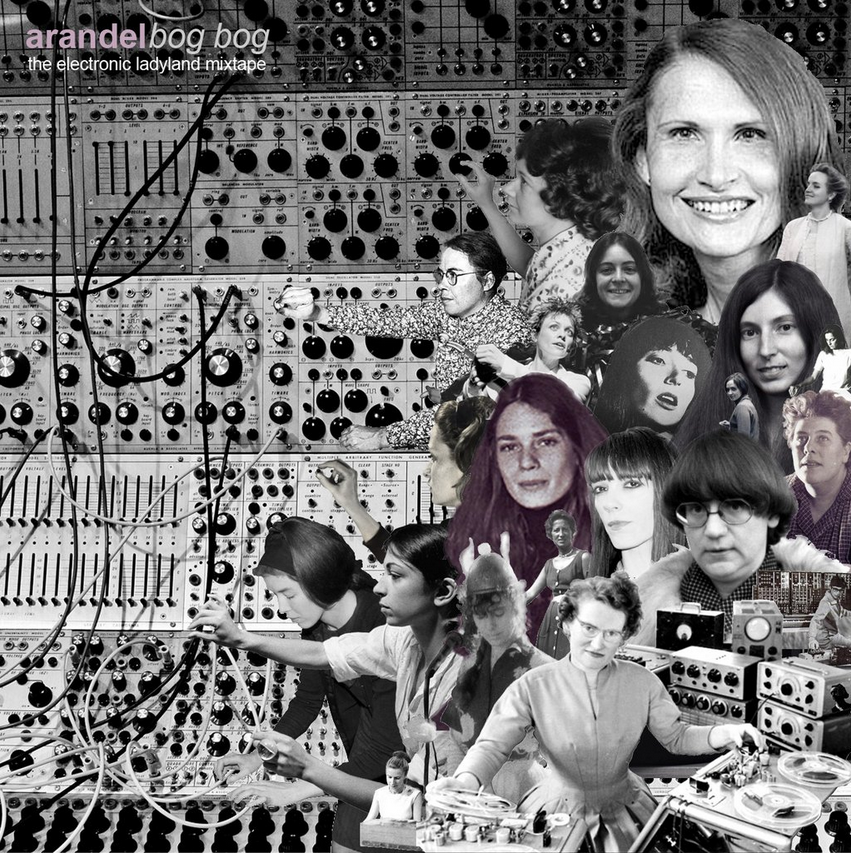

But as you can see in the short documentary clip at the top, the Swing Kids’ resistance to the by-now familiarly disturbing, paramilitary regimentation of German young people (see above), was in its way a radical act. “Their casual, fun-loving attitude made a mockery of Nazi control,” the documentary narrator says. They embraced what was “considered ‘degenerate music’ by Nazi ideology,” writes MessyNChic, “because it was often performed by black and Jewish musicians and promoted free love.”

We cannot assume the Swing Kids’ love of the music extended to a love for the people who made it. It’s more so the case that the Swing Kids “admired the British and American way of life,” and the free-spiritedness universally represented at the time by jazz in American and British films and records, to which German youth had some limited access. But in their battle for “self-determination and freedom,” informal groups like the Edelweiss Pirates, the Traveling Dudes, and the Navajos resisted subordination into a homogenized Aryan mass—the mechanism by which Hitler turned ordinary Germans into loyal abettors of mass murder.

Through fashion and music, the Swing Kid clubs—like the rockers or punks of the U.S. and U.K. in later decades—formed in conscious resistance to social and political conformity. The Navajos wrote the following song, for example:

Hitler’s dictates make us small,

we’re yet bound in chains.

But one day we’ll again walk tall,

no chain can us restrain.

For hard are our fists,

Yes! And knives at our wrists,

for youth to be free,

Navajos lay siege.

The references to violence weren’t purely symbolic. Swing Kid gangs fought Hitler Youth in the streets. Some Swing Kids, writes MessyNChic, became known for “tagging public walls with anti-Nazi slogans like ‘Down with Hitler!’ and ‘Medals for Murder!’. Throwing bricks through windows and sabotaging cars of Nazi officials… raiding military bases… derailing trains… even planning to blow up the Gestapo HQ in Cologne.” And as the educational site Music and the Holocaust documents, the Gestapo fought back “with special cruelty” against Swing Boys and Swing Girls.

In Hamburg, Swing Kids “had to endure discriminating interrogations, torture and detention.” They landed in youth concentration camps, and adult and Jewish “swing members… were deported” to death camps in Bergen-Belson, Buchenwald, Auschwitz, and elsewhere. MessyNChic claims that “a file compiled by the Gestapo is said to have contained more than 3,000 names [of Swing Kids] already by the end of the 1930’s in Cologne alone. In terms of numbers, that would mean these youths represented a much larger resistance potential than any other opposition group in Germany made up by adults.”

Again, none of this organized resistance constituted an explicit political program. “The Swing Kids themselves never intended to have any political effects,” writes Swingstyle, “they did not understand politics” and “they turned their backs on the reality around them: the Jewish roundups, the death camps and the steady stream of manpower reserves disappearing into the cauldrons of Russia and France.” Swing was a means of escapism and identification with the more relaxed, permissive “paradises” of America and Britain.

Like teenagers living under any regime, Swing Kids were mainly motivated by sex and the search for a good time. But perhaps the anarchic strength of their most primal instincts made these young people some of the most effective resistance fighters against the Nazi obsession with purity and order. Their lives—choreographed to the tunes of Count Basie and Benny Goodman—were “in complete opposition to the perceived National Socialist concept of youth,” concludes Swingstyle: “To the extent that the Swing Kids assumed American ideals of personal freedom, relaxed living, and appreciation of the ‘lower races’… they were a grave threat to the upside-down philosophy of Nazism that sought to insulate Germany from the rest of the world.”

Their embrace of an international, racially-mixed culture—jazz—was itself a radical political act in Nazi Germany, even if they had no theoretical concepts of what that embrace meant for the future of their country. And their violent rejection of the Hitler Youth makes them even more compelling. It seems to me that the Swing Kids do indeed deserve a celebratory place in history—and maybe they deserve a better film as well.

Related Content:

Hear the Nazi’s Bizzaro Propaganda Jazz Band, “Charlie and His Orchestra” (1940–1943)

The Nazis’ 10 Control-Freak Rules for Jazz Performers: A Strange List from World War II

Watch Lambeth Walk—Nazi Style: The Early Propaganda Mash Up That Enraged Joseph Goebbels

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness