In a recent interview, the perennially cheerful Paul McCartney talked candidly about his depression after the Beatles’ 1970 breakup, a revelation that may have come as a surprise to some people given Sir Paul’s general level of, well, cheer. But, “you would be too if it happened to you,” said McCartney, admitting that he “took to the bevvies… to a wee dram” (and making even a drinking problem sound upbeat). Where McCartney admits he struggled to find his footing again musically, two of his estranged bandmates released solo-career-defining albums just months after the Beatles’ official demise—George Harrison’s All Things Must Pass and John Lennon’s Imagine.

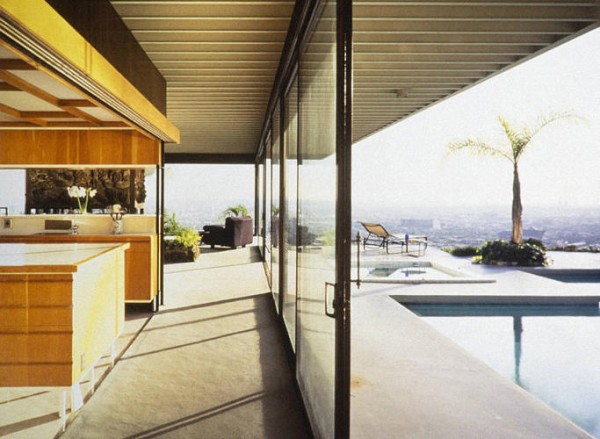

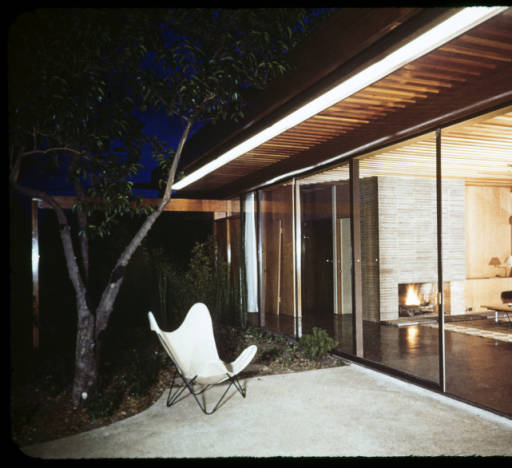

Lennon, of course, had his own post-Beatles issues with substance abuse and depression. But in 1971 he had kicked a heroin habit, embraced primal therapy, and was in top musical form. Not only did Imagine, the album, go double platinum, but fans and critics consider “Imagine,” the song, one of the finest Lennon ever wrote. In the footage above, we see Lennon during the early Imagine recording sessions at his home studio at Tittenhurst Park. Lennon plays the new title track for the album’s musicians for the first time, records his vocals and piano, and discusses the mix and arrangement with Phil Spector and Yoko Ono.

The clip comes from the 2000 documentary Gimme Some Truth: The Making of John Lennon’s Imagine Album, which captures the intimacy of those recording sessions, as Lennon and his band eat and talk together before going into the studio. George Harrison appears often to record guitar parts for several songs; the band jams and horses around; Allen Ginsberg and Miles Davis show up and Davis plays basketball with Lennon; and Yoko and John discuss design and album photography.

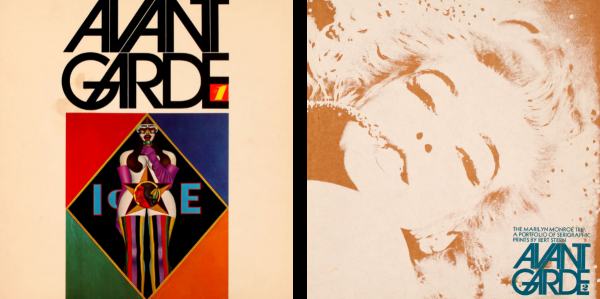

Later that year, Lennon and Yoko appeared on The Dick Cavett Show to promote the song and album and premier the “Imagine” film above. As in nearly all of his solo work, Ono acted both as Lennon’s muse and his collaborator, inspiring Imagine’s “How” and “Oh Yoko” and co-writing “Oh My Love.” She is rarely given credit, however, for inspiring—and co-writing—“Imagine.” The song owes much to Ono’s “good-naturedly defiant little book,” Grapefruit, “part irreverent activity book for grown-ups,” writes Maria Popova, “part subversive philosophy for life,” complete with whimsical drawings very much like the kind Lennon himself made and published in his own books of silly verse.

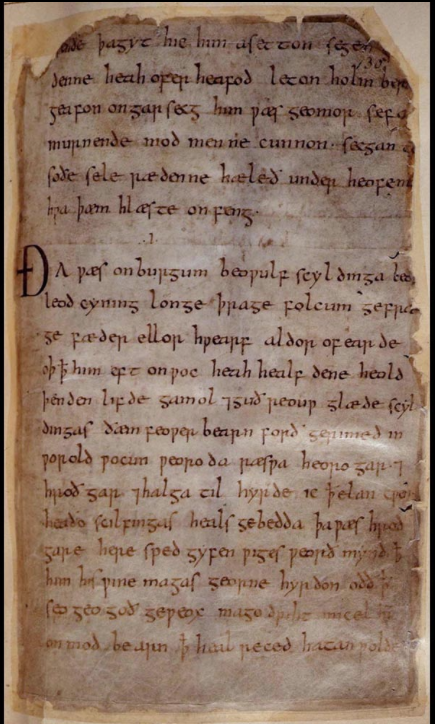

But while critics and Lennon fans overlook Yoko’s role in “Imagine”’s composition, Lennon later admitted it “should be credited as a Lennon/Ono song. A lot of it—the lyric and the concept—came from Yoko, but in those days I was a bit more selfish, a bit more macho, and I sort of omitted her contribution, but it was right out of Grapefruit.” The album cover did, however, quote “Cloud piece,” one of the many meditative poems Lennon drew from: “Imagine the clouds dripping. Dig a hole in your garden to put them in.”

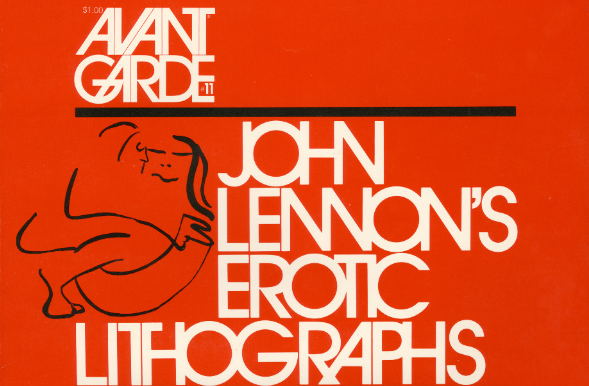

In the short making-of clip at the top, Lennon tells the room, after playing a raw rendition of “Imagine” solo on piano, “that’s the one I like best.” The song’s utopianism strongly contrasts with the righteous anger and bitterness Lennon gave vent to in other songs on Imagine, including “How Do You Sleep?,” in which, he told Playboy in 1980, “I used my resentment and withdrawing from Paul and The Beatles, and the relationship with Paul.” Early editions of the LP even included a postcard photo of Lennon holding a pig, mocking the cover of McCartney’s underrated Ram. McCartney expressed his post-Beatles’ anger in a few minor lyrical jabs; Lennon responded with unsubtle vitriol. But many of Imagine’s songs—celebrations of love, protests against war, and the visionary title track—point away from the past and toward the future, or what little of it remained for Lennon.

Related Content:

John Lennon & Yoko Ono’s Two Appearances on The Dick Cavett Show in 1971 and 72

John Lennon’s “Imagine” & Paul McCartney’s “Yesterday” Adapted into Smart, Moving Webcomics

Hear John Lennon’s Final Interview, Taped on the Last Day of His Life (December 8, 1980)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness