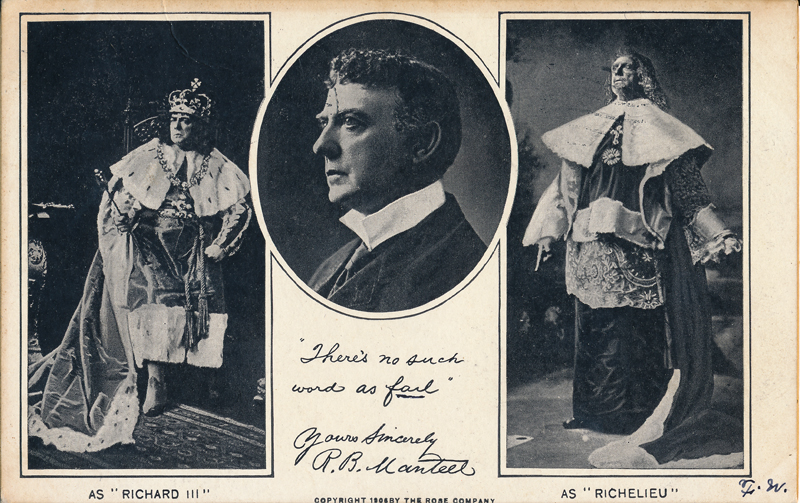

We’ll never fully know how anything looked in Shakespeare’s time, much less how the Bard’s own plays did when first performed on the stage of the Globe Theatre. Thorough scholarship of history in general and Shakespeare in particular has enabled us to imagine and reconstruct such a sight with reasonable credibility, but only so much direct accuracy, since the development of photography wouldn’t happen for a couple hundred years. But not long after humanity got its photographers did those photographers begin taking pictures of humanity’s best-known dramas, and a set of particularly vivid examples survives on Emory University’s relaunched web site Shakespeare and the Players.

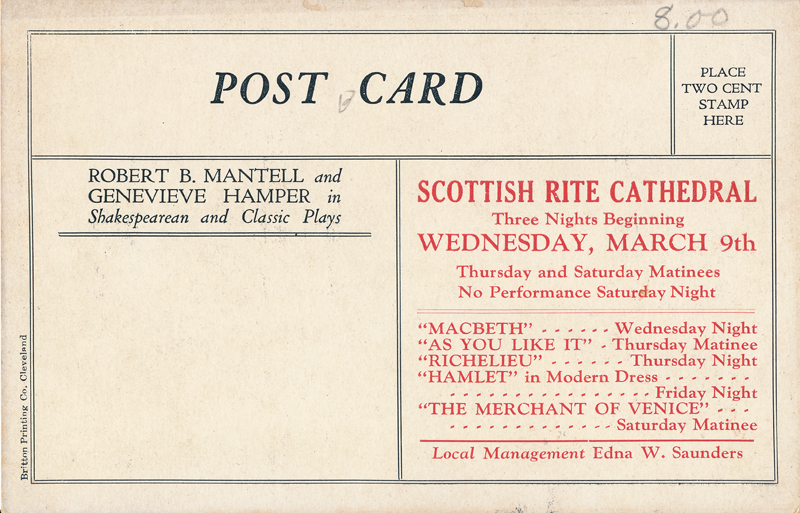

The site describes itself as “an online exhibition of nearly 1,000 postcards featuring many famous English and American actors who performed Shakespeare’s plays for late Victorian and Edwardian audiences,” specificially from around 1880 to 1914. It “showcases postcards featuring the dominating actors of the time in roles from some of the more popular and oft-performed plays, like Hamlet and Romeo & Juliet, as well as those from plays not often performed, like Cymbeline and The Merry Wives of Windsor.”

Slate’s Rebecca Onion refers to scholar Lawrence W. Levine, who writes of how, in the 19th century, “many Americans, even if illiterate, knew and loved Shakespeare’s plays; they were the source material for endless parodies, skits, and songs on the American stage. Nor was Shakespeare fandom confined to the elite; in the first half of the 19th century, theater ‘played the role that movies played in the first half of the twentieth … a kaleidoscopic, democratic institution presenting a widely varying bill of fare to all classes and socioeconomic groups.’ ”

Shakespeare and the Players first went live back in the 1990s, a project of English professor Harry Rusche, who has written an informative preface for the site in its recently redesigned form (with its images completely re-digitized). “Postcards on Shakespeare appeared in a dizzying array of contexts,” he explains, “some humorous and some serious; these cards of actors were only a small part of Shakespeare and of the card-industry as a whole.” A “mania for collecting” swept up their contemporary buyers, not to mention an appreciation for the stars of the day: “handsome men and beautiful women are always popular in any medium.”

But plenty of them actually used these postcards for their intended purpose, about which you can learn more on the site’s postcard backs section. It notes that “the philosopher Jacques Derrida, in The Postcard, encourages us to read the two conflicting, yet resonating scenes — in our case, the Shakespeare image and the handwriting on the back — two sides of the postcards together,” an experience that may “be especially interesting to those of us born in the age of email, video conferences, Twitter, and text messaging,” those who will now wonder when a set of Shakespeare emoji will come along, providing us a means of continuing to incorporate these eternal characters into our correspondence today.

Related Content:

Free Online Shakespeare Courses: Primers on the Bard from Oxford, Harvard, Berkeley & More

Read All of Shakespeare’s Plays Free Online, Courtesy of the Folger Shakespeare Library

Shakespeare’s Restless World: A Portrait of the Bard’s Era in 20 Podcasts

Take a Virtual Tour of Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre

Drunk Shakespeare: The Trendy Way to Stage the Bard’s Plays in the US & the UK

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.