We all know the rules of art museums: look, but don’t touch. This doesn’t bother most of us most of the time, but for art-lovers who happen to be blind and thus use feeling as a substitute for seeing, it presents a problem indeed — but it also opens up an artistic opportunity. “Cantor Fine Art, a just-launched gallery by father and son team Larry and Sam Cantor, offers a story of a different kind of physical interaction with art in their project, Please Touch the Art,” writes The Creator’s Project’s Gabrielle Bruney. “They partnered with artist Andrew Myers to create a tactile painting that is appreciable by both sighted and blind art lovers.”

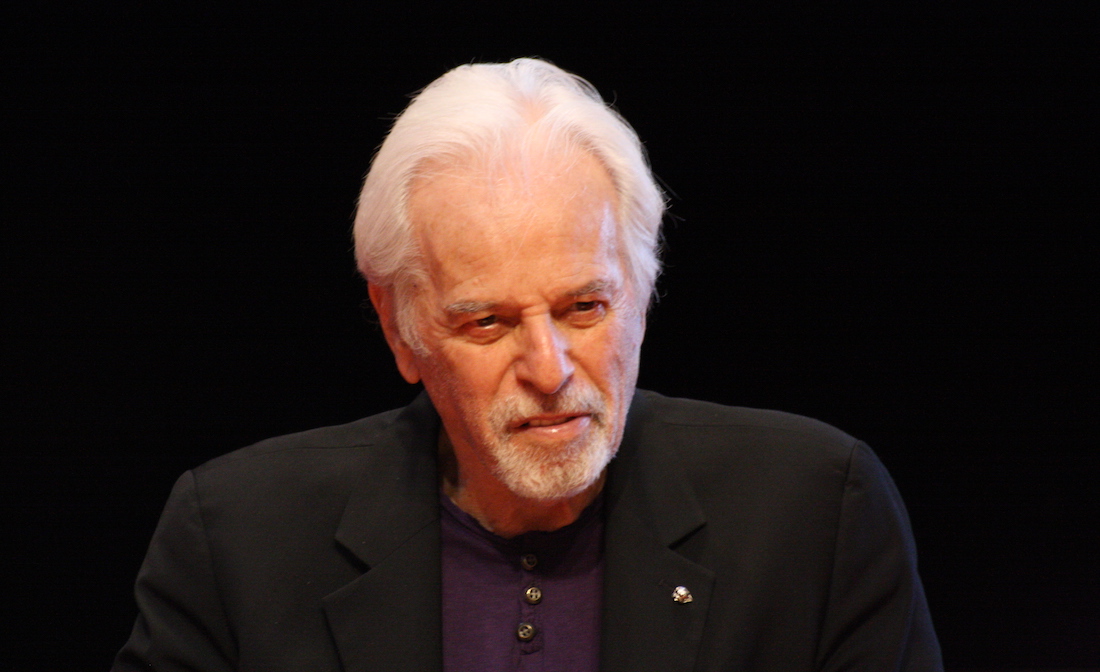

In the five-minute video above, you can see — or if visually impaired, hear — Myers discussing the beginnings of his “screw pieces,” images made by driving countless screws into a piece of wood, each one ultimately acting as a kind of physical, three-dimensional pixel. Though Myers didn’t begin these works with the blind in mind, one such gallery-goer’s visit to his show, and the “huge smile on his face” when he put his hand to the screw pieces, got him thinking of the possibilities in that direction. Thanks to his art, “there was a blind man who could almost see for a second.”

We also meet the blind woodworker George Wurtzel, currently at work on “converting an old grape crushing barn into a Tactile Art Center” which combines a woodworking shop with a “tactile gallery space where the visually impaired can experience and sell artwork.” Discovering their shared passion for tactile art, Myers decides to make a surprise for Wurtzel, “the first portrait of himself he can actually feel,” the first new piece for his tactile art gallery. The video captures the big reveal, which converts Wurtzel from his skepticism about the screw-piece form. Still, even as he runs his fingers over his own metallicized features, he has his objections: “My nose is not that big. I’m sorry. I like the beard, though. The beard is good. The beard is really good.”

You can read more about the project at Cantor Fine Art’s web site. “The one thing I wish,” Myers adds, “is that George could see the piece the way I see it, but at the same time, I would like to look at things the way he sees the world.” You can get more a sense of art as seen, as Billy Joel once sang, by the eyes of the blind in our previous posts on the Prado’s 3D-printed exhibition for the visually impaired and the experience of the colorblind seeing art in color for the first time. It seems we’ve found ourselves at the dawn of a new golden age for art that doesn’t require sight. If a gallery boom follows, will they serve coffee roasted by the Unseen Bean?

Related Content:

What It’s Like to Be Color Blind and See Art in Color for the First Time

Jorge Luis Borges, After Going Blind, Draws a Self-Portrait

Wake Up and Smell the Coffee with Blind Master Roaster Gerry Leary

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.