The affinities between England and Japan go far beyond the fact that both are tea-loving nations with a devotion to gardens; far beyond the fact that both drive on the left, are the world’s leading overseas investors, and are rainy islands studded with green villages. They go even beyond the fact that both have an astringent sense of hierarchy, subscribe to a code of social reticence, and are, in some respects, proud, isolated monarchies with more than a touch of xenophobia. The very qualities that seem so foreign, even menacing, to many Americans in Japan — the fact that people do not invariably mean what they say, that uncertain distances separate politeness from true feelings, and that everything is couched in a kind of code in which nuances are everything — will hardly seem strange to a certain kind of Englishman.

That astute comparison comes from an essay called “For Japan, See Oscar Wilde” by Pico Iyer, a writer uniquely well-placed to sense this sort of thing by virtue of his childhood in England and longtime residence as an adult in Japan. His Indian heritage and penchant for world travel have also equipped him to write with clarity about the ways — sometimes grotesque, sometimes delusional, sometimes aspirational, sometimes fantastical — in which one country can perceive another.

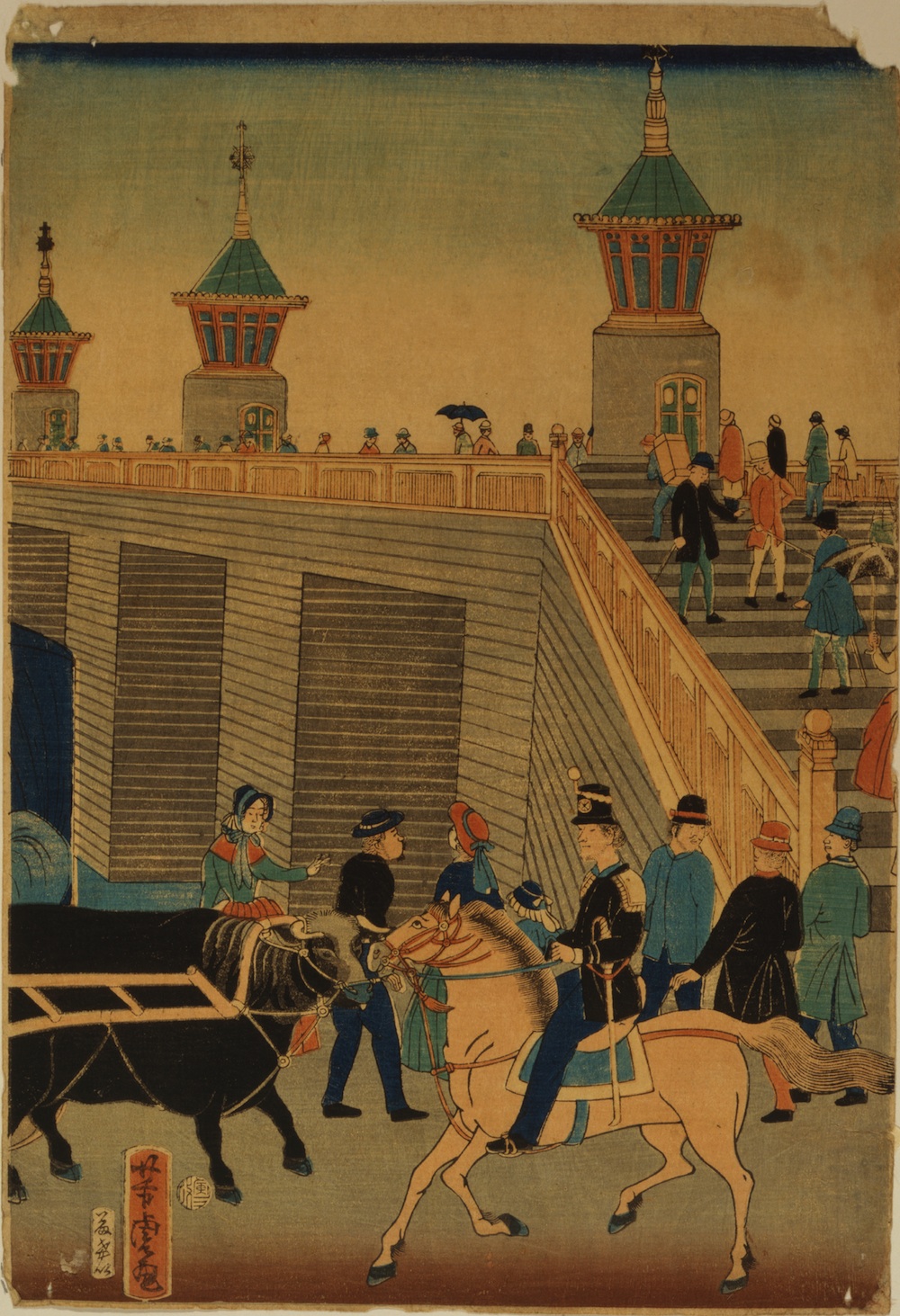

In the case of the somehow separated-at-birth nations of England and Japan, we have some direct documentation of the former as dreamed of by the latter in Utagawa Yoshitora’s 1866 triptych Igirisukoku Rondon no zu.

“Together, the three images depict a street scene near the River Thames, complete with thronging English pedestrians, two sailing ships, horses, oxen, and carriages,” writes Slate’s Rebecca Onion: “The images would have sold fairly cheaply, in the thriving market in woodblock (ukiyo‑e) prints in 19th-century Japan. Utagawa, a relatively minor artist from an extensive lineage of woodblock printers, also produced portraits of Kabuki actors, triptychs of historical battle scenes, and images of foreigners in Yokohama—one of the only places in Japan where they were allowed to trade at the time. (Here’s an 1861 print titled ‘Two Americans.’) Utagawa probably did not visit London, and was instead working from secondhand reports.”

That would make him a perfect subject for Iyer, who has tended to specialize in writing not just about the places of the world but the places of the mind. While the people of Utagawa’s London of the mind display a simplified typical English style of dress, and do so before a proud domed building and a mighty-looking, elaborately rigged sailing ship, their composition remains somehow quintessentially Japanese. But then, how much separates the quintessentially Japanese from the quintessentially English? “The actual people who live in Japan,” said Oscar Wilde as quoted in Iyer’s essay, “are not unlike the general run of English people.”

And the affinity goes both ways. When Prince Fushimi Sadanaru made a state visit to England forty years after Utagawa made his prints, he hoped to catch a performance of The Mikado, Gilbert and Sullivan’s hit comic opera set very much in the Japan of the English mind (and one that faces accusations of cultural imperialism to this day). Alas, the British government had preemptively canceled all performances during the Prince’s stay for fear of offending him. This prompted a Japanese journalist in London to later see the show himself. He went on to write of his disappointment: he’d gone in expecting “real insults” to his homeland, only to find “bright music and much fun.”

via Slate’s The Vault/Two Nerdy History Girls

Related Content:

London Mashed Up: Footage of the City from 1924 Layered Onto Footage from 2013

2,000 Years of London’s Historical Development, Animated in 7 Minutes

Prize-Winning Animation Lets You Fly Through 17th Century London

1927 London Shown in Moving Color

Download Hundreds of 19th-Century Japanese Woodblock Prints by Masters of the Tradition

The Best Writing Advice Pico Iyer Ever Received

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.