“If you remember the sixties,” goes the famous and variously attributed quotation, “you weren’t really there.” And, psychological after-effects of first-hand exposure to that era aside, increasingly many of us weren’t born anywhere near in time to take part.

Those of us from the wrong place or the wrong time have had to draw what understanding of the sixties we could from that much-mythologized period’s music and movies, as well as the cloudy reflections of those who lived through it (or claimed to). But now we can get a much more direct sense through the complete digital archives of Oz, sometimes called the most controversial magazine of the sixties.

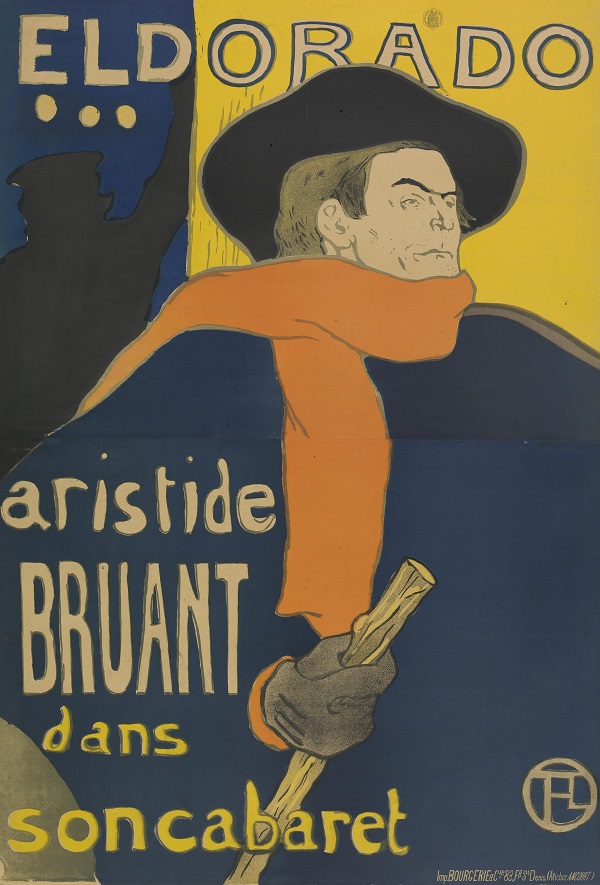

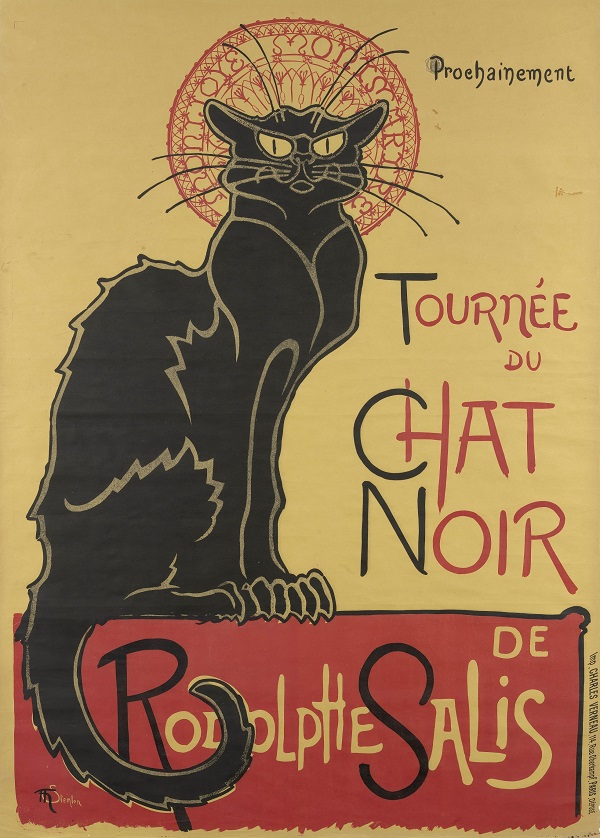

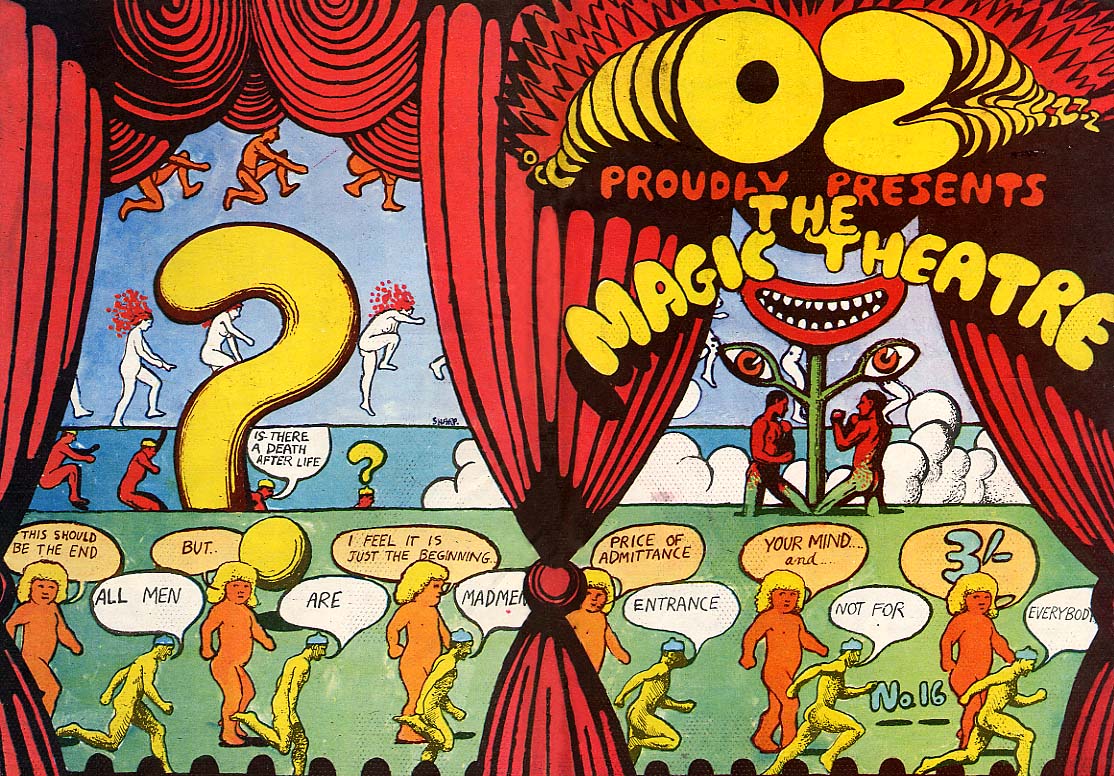

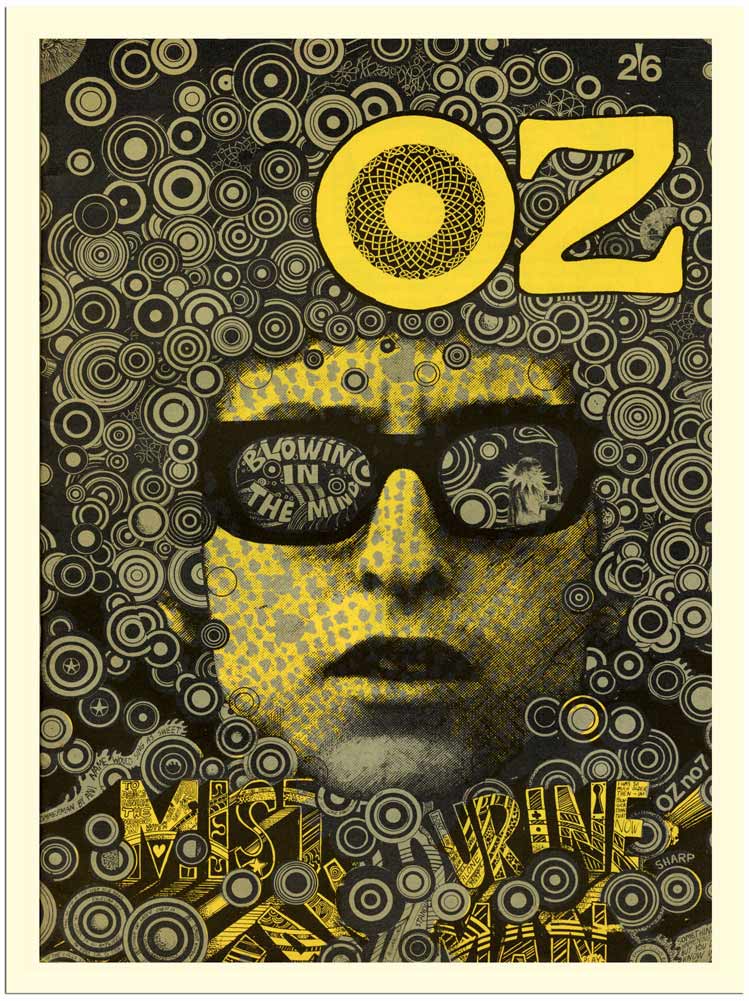

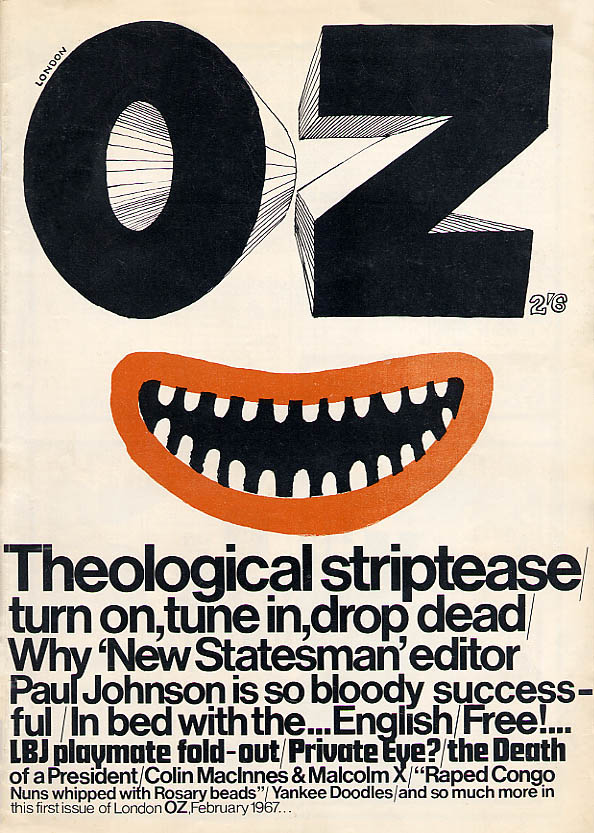

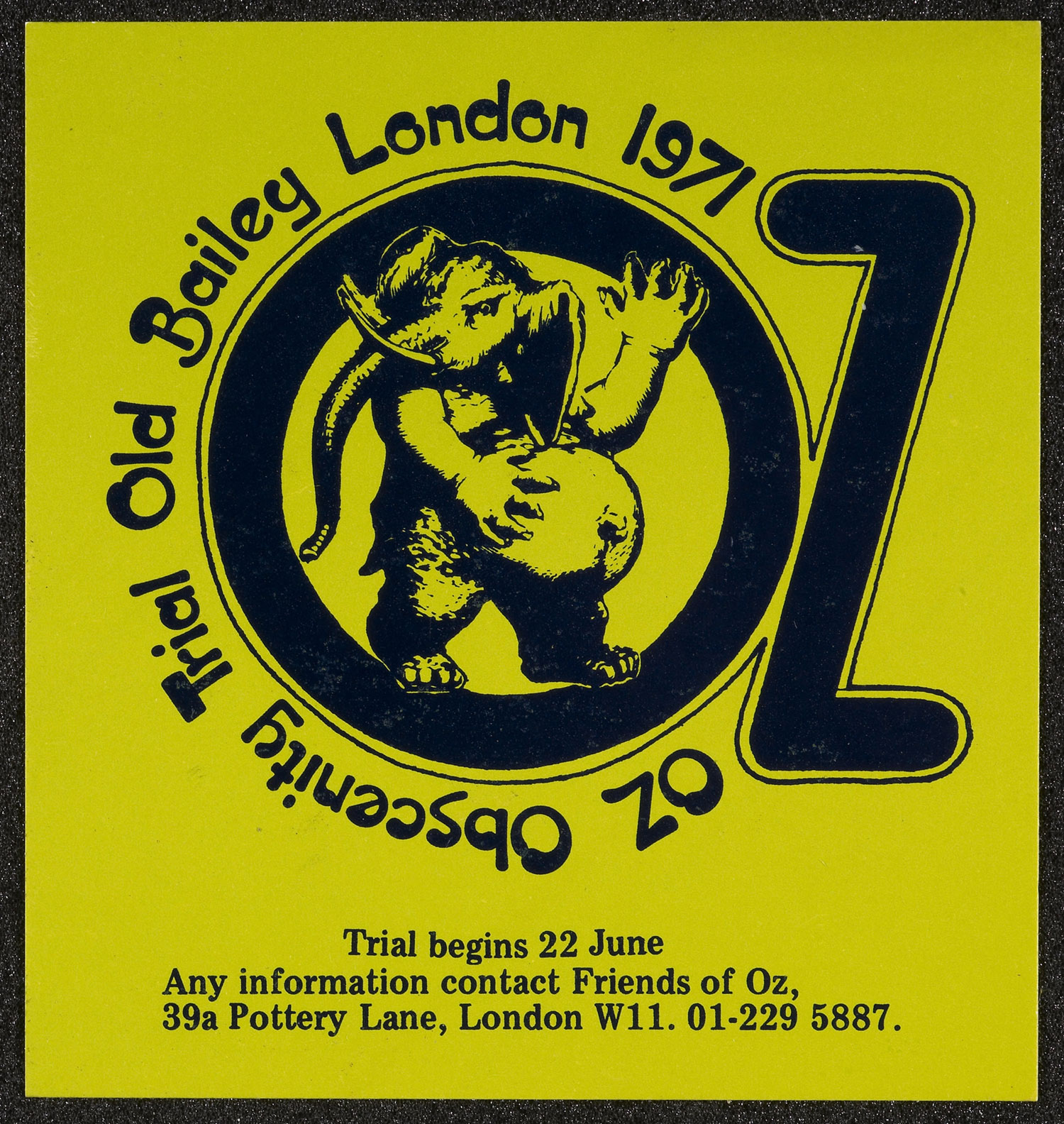

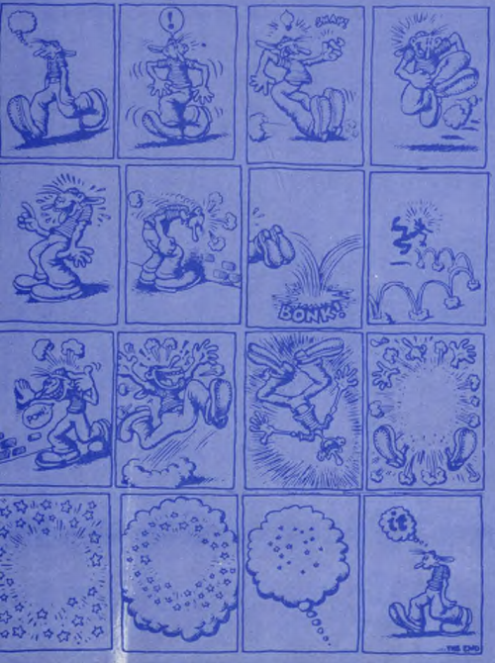

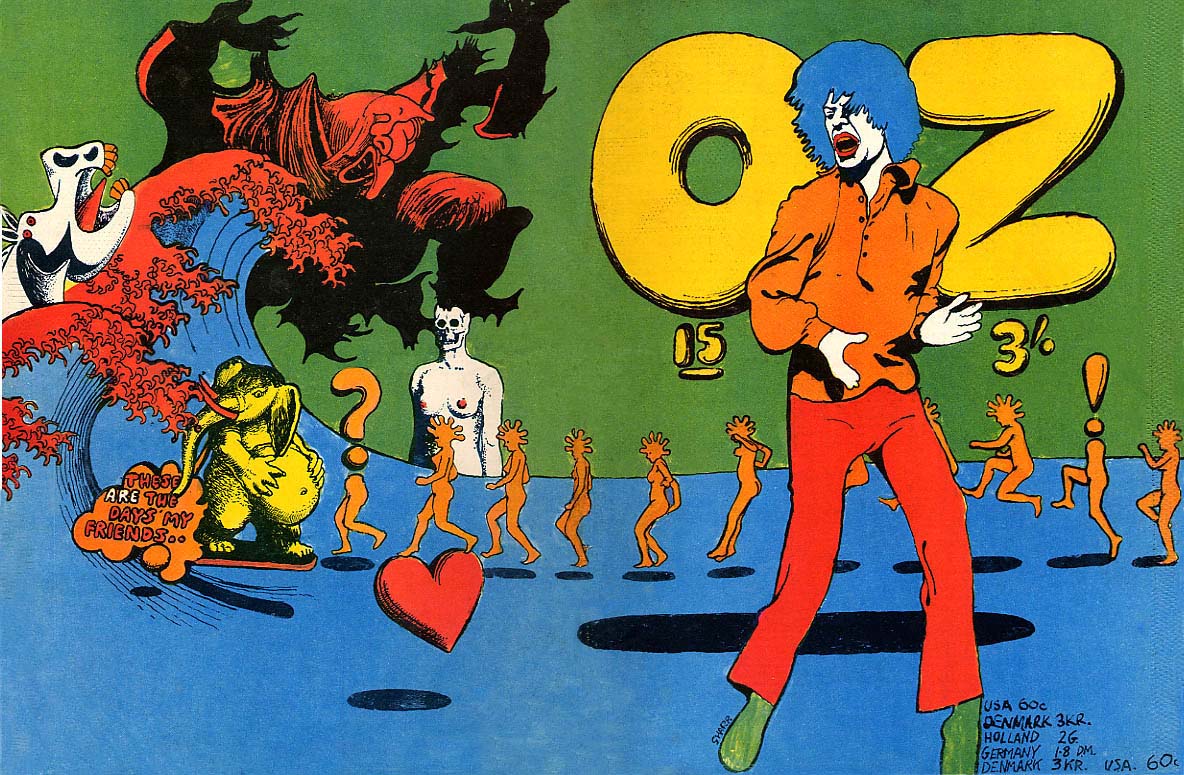

In The Guardian, Chitra Ramaswamy describes the London magazine as “the icon – and the enfant terrible – of the underground press. Produced in a basement flat off Notting Hill Gate, Oz was soon renowned for psychedelic covers by pop artist Martin Sharp, cartoons by Robert Crumb, radical feminist manifestos by Germaine Greer, and anything else that would send the establishment apoplectic. By August 1971, it had been the subject of the longest obscenity trial in British history. It doesn’t get more 60s than that.” Even its print run, which began in 1967 and ended in 1973, perfectly brackets the period people really talk about when they talk about the sixties.

The online archive has gone up at the web site of the University of Wollongong, who two years ago put up a similar digital collection of all the issues of Oz’s eponymous satirical predecessor produced in Sydney. “Please be advised,” notes the front page, “this collection has been made available due to its historical and research importance. It contains explicit language and images that reflect attitudes of the era in which the material was originally published, and that some viewers may find confronting.” And while Oz today wouldn’t likely get into the kind of deep and high-profile legal trouble it did back then — in addition to the famous 1971 trial for the London version, the Sydney one got hit with two obscenity charges during the previous decade — the sheer transgressive zeal on display all over the magazine’s pages in its heyday still impresses.

“Fifty years later, it’s important as a capsule of the times, but also as a work of art,” says Michael Organ, a library manager at the university, in the Guardian article. “Oz is a record of the cultural revolution. Many of the issues it raised, such as the environment, sexuality and drug use, are no longer contentious. In fact, they have now become mainstream.”

All this goes for the deliberately provocative editorial content — the stuff some viewers may find “confronting” — as well as the incidental content: ads for novels by Henry Miller and Jean Genet, “dates computer matched to your personality and tastes,” a machine promising “a hot line to infinity/journey through the incredible landscapes of your mind/kaleidoscopic moving changing image on which your mind projects its own changing/stun yourself & astonish friends,” and the “liquid luxury” of the Aquarius Water Bed. It does not, indeed, get more sixties than that. Enter the Oz archive here.

Related Content:

Tonite Let’s All Make Love in London (1968): An Insider’s View of 60s London Counterculture

R. Crumb Describes How He Dropped LSD in the 60s & Instantly Discovered His Artistic Style

62 Psychedelic Classics: A Free Playlist Created by Sean Lennon

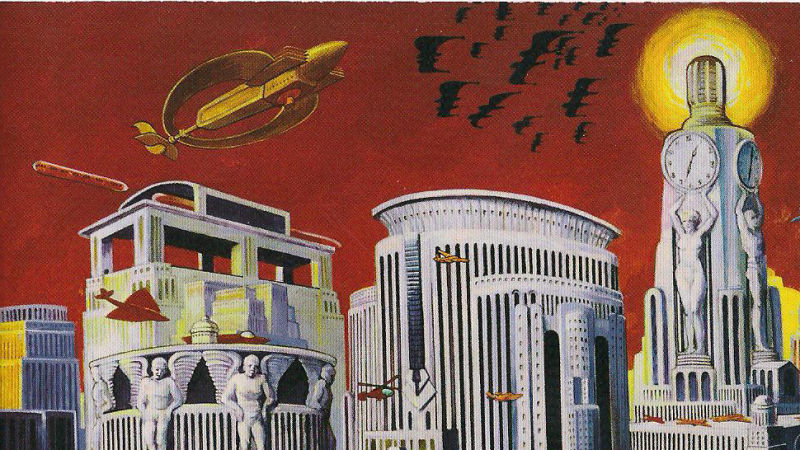

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.