As you’ve probably noticed if you’re a regular reader of this site, we’re big fans of book illustration, particularly that from the form’s golden age—the late 18th and 19th century—before photography took over as the dominant visual medium. But while photographs largely supplanted illustrations in textbooks, magazines, and newspapers over the course of the 20th century, works of fiction, which had been routinely published in lavishly illustrated editions, suddenly became the featureless banks of words we know today. Though image-heavy graphic novels and comic books have thrived in recent decades, the illustrated literary text is a rarity indeed.

Why did this change come about? “I really don’t know,” writes Christopher Howse at The Telegraph, but he points out that the era of illustrated fiction for grown-ups ended “after the death of the big Victorian novelists,” like Dickens and Trollope. Before adult picture-books went out of style, several now-famous artists made careers as book illustrators. When we think of the big names from the period, we think of Aubrey Beardsley and Gustave Doré, both of whom we’ve covered heavily here. We tend not to think of Irish artist Harry Clarke—a relative latecomer—but we should. Of the many incredible illustrations from famous works of literature we’ve featured here, my favorite might be Clarke’s 1926 illustrations of Goethe’s Faust.

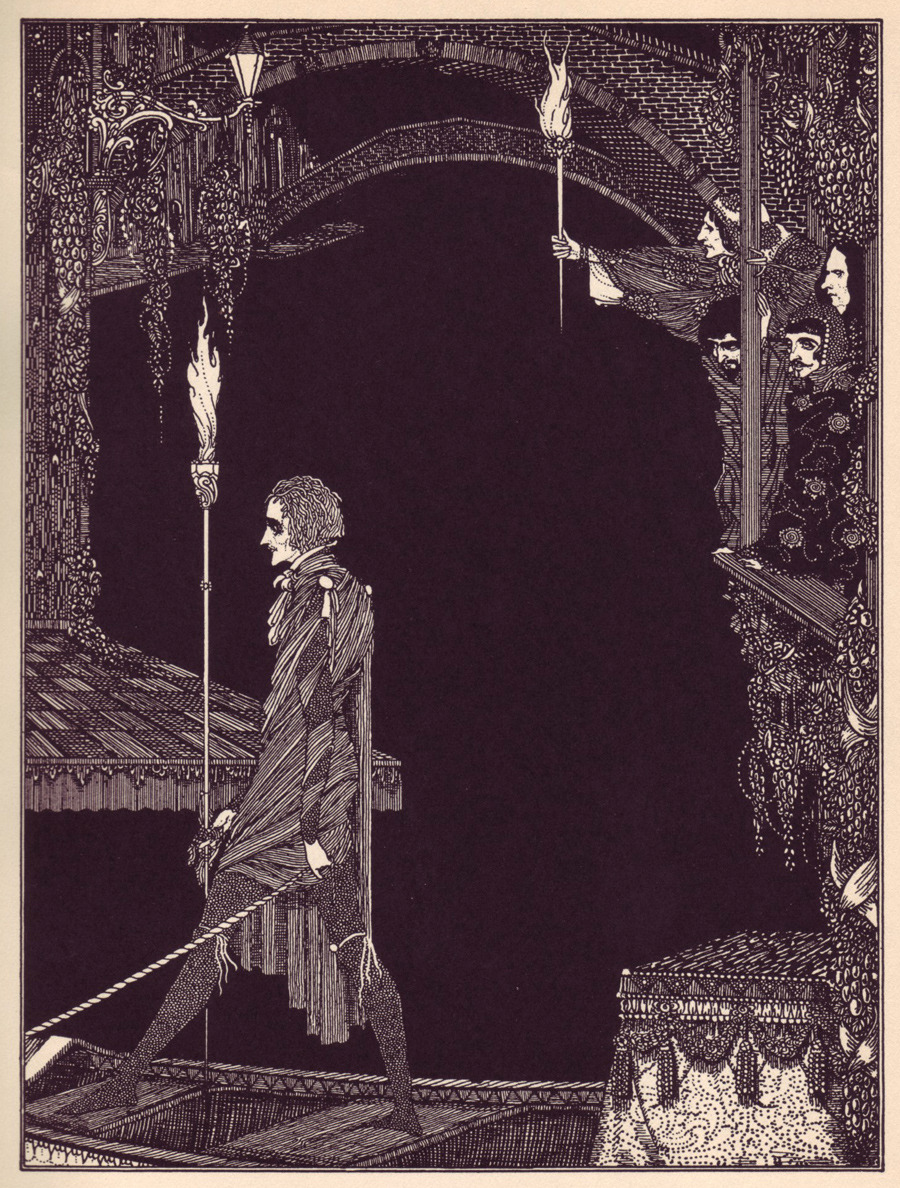

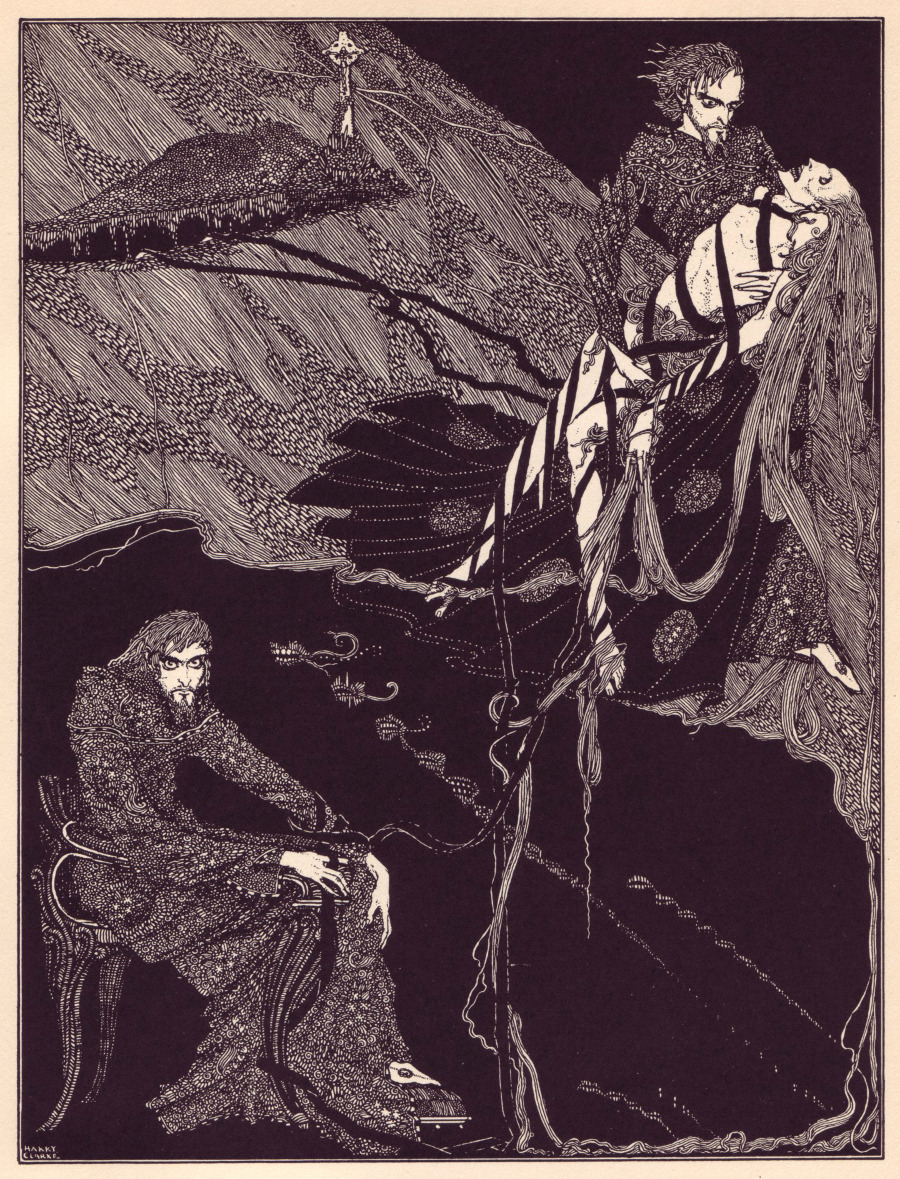

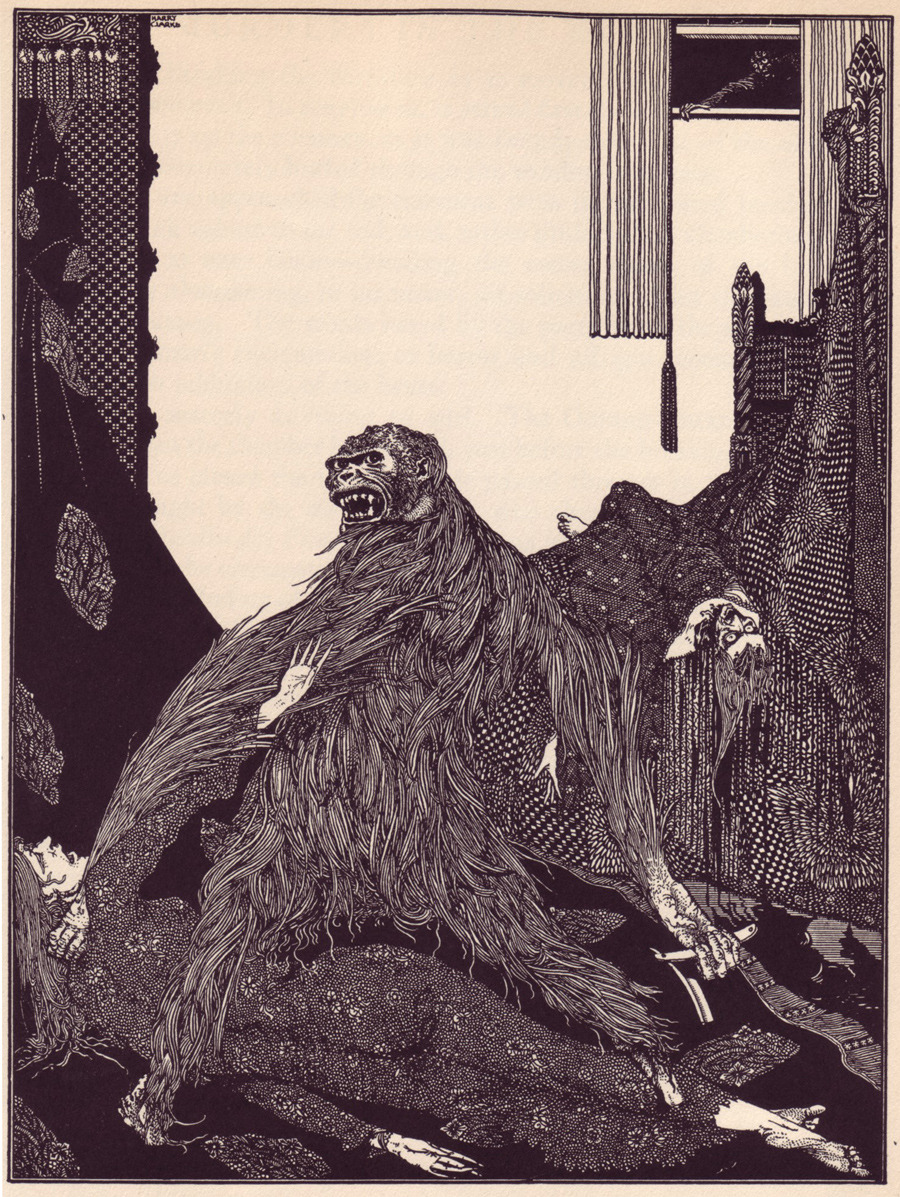

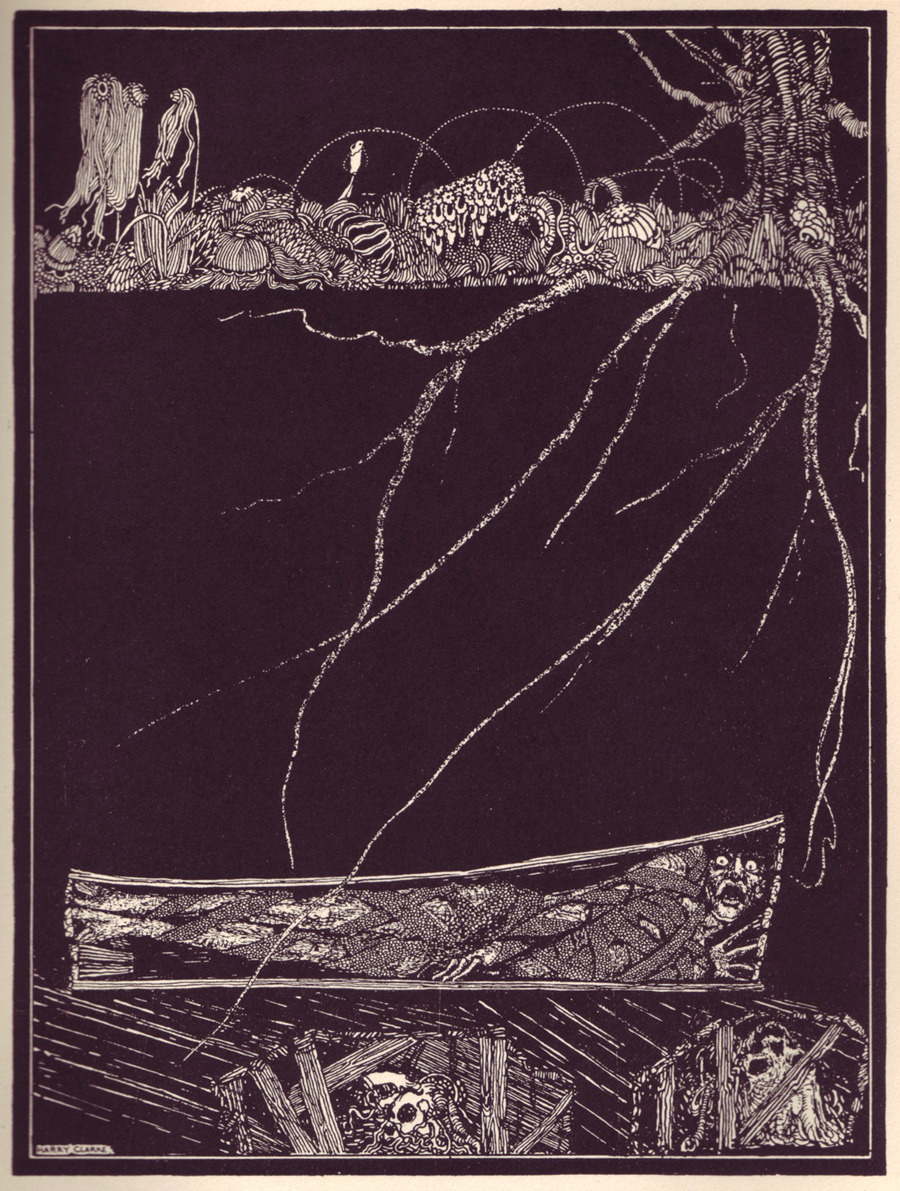

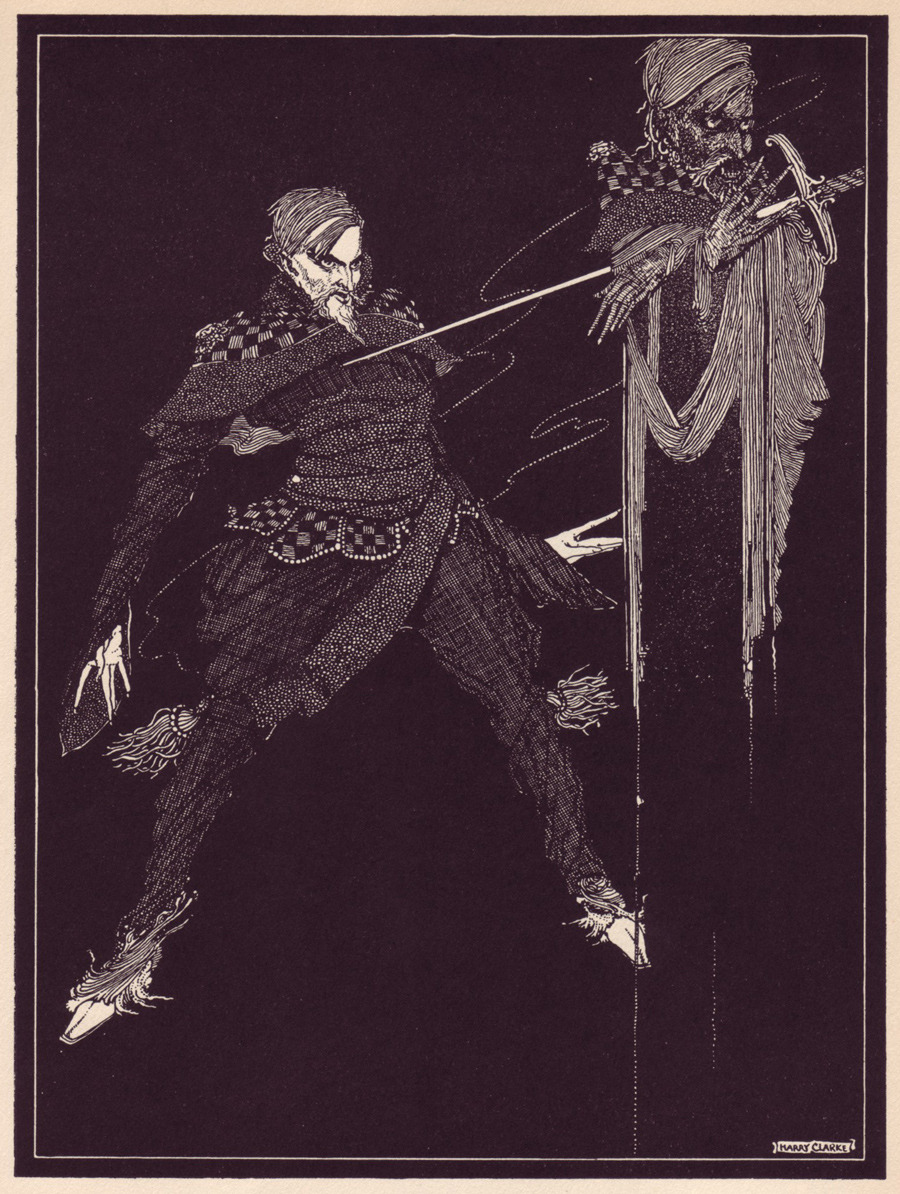

So out-there are some of his illustrations, so delightfully nightmarish and weird, one is tempted to fall back on that rather sophomoric explanation for art we find disturbing: maybe he was on drugs! Not that he’d need them to conjure up many of the images he did. His source material is bizarre enough (maybe Goethe was on drugs!). In any case, we can definitely call Clarke’s work hallucinatory, and that goes for his earlier, 1923 illustrations of Edgar Allan Poe’s Tales of Mystery and Imagination as well, of which you can see a few choice examples here.

Dublin-born Clarke worked as a stained-glass artist as well as an illustrator, and drew his inspiration from the earlier art nouveau aesthetic of Beardsley and others, adding his own rococo flourishes to the elongated forms and decorative patterns favored by those artists. His glowering figures—including one who looks quite a bit like Poe himself, at the top—suit the feverish intensity of Poe’s world to perfection. And like Poe, Clarke’s art generally thrived in a seductively dark underworld filled with ghouls and fiends. Both of these proto-goths died young, Poe under mysterious circumstances at age 40, Clarke of tuberculosis at 42.

Clarke’s illustrated edition of Poe contained 8 full-color plates and 24 black and white illustrations. The Irish artist also notably illustrated editions of the fairy tales of Hans Christian Andersen and Charles Perrault, with images that—as you might imagine—are likely to terrify some sensitive children. You can purchase your own edition of the Clarke-illustrated Poe here, re-released in 2008 by Calla Press. And to see all 24 of Clarke’s black and white plates, head over to 50 Watts.

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2016.

Related Content:

Gustave Doré’s Macabre Illustrations of Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven” (1884)

Aubrey Beardsley’s Macabre Illustrations of Edgar Allan Poe’s Short Stories (1894)

Harry Clarke’s 1926 Illustrations of Goethe’s Faust: Art That Inspired the Psychedelic 60s

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Looking for an Edward Gorey vibe, are we?

I actually own a copy of the book. My father retrieved it out of my grandparents home after they passed. I’ve had it since, approx. 35 yrs.

Have you read Gustave Dore’s London above and Below ? A must see