Can a computer game teach writing and free up the creative mind? Elegy for a Dead World, a Kickstarter-funded game for Steam PC, Mac and Linux systems, hopes to do so. The creators Ichiro Lambe and Ziba Scott brought the game to E3 last year and debuted it with a brief introductory walkthrough.

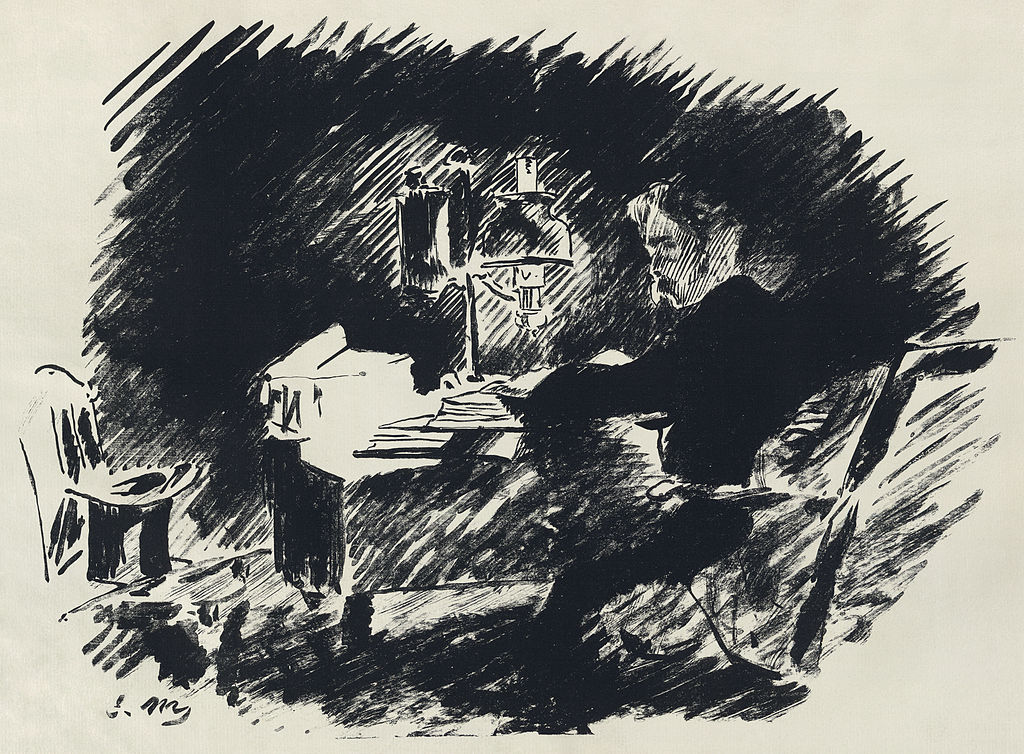

The game contains three post-apocalyptic worlds based on the works of a trio of Romantic poems: Ozymandias by Percy Bysshe Shelley, Darkness by Lord Byron, and When I Have Fears That I May Cease to Be by John Keats.

Players explore the world by walking and flying through it like a regular platform game, but encounter writing prompts that begin to flesh out the backstory with the help of the player’s imagination. The developers hope that by the third or forth prompt, the player will be invested in the tale they are telling and perhaps ignore the prompts altogether.

Players can share their stories with friends. They can also print out their finished work through sites like Blurb and Lulu.

It’s hard to know without spending the $14.99 whether or not Elegy really can lead you to some decent writing. Experienced writers may find the worlds too limiting, but perhaps for a beginning writer it might help with the fear of the blank page. A lot was promised in the Kickstarter campaign:

You can read other players’ works, browsing through the most-recent, the best-loved, and recently-trending stories. In our gameplay tests so far, players have expressed a variety of thoughts about what happened in each world — the silhouette of what looks like a telescope to one player looks like a rocket ship to another, and a planet-destroying weapon to yet another.

In a larger context, Elegy is another attempt by game designers to free players from the determination of goal-based, narrative video games. Leave a comment if you’ve played Elegy for a Dead World and if you created something out of it. In the meantime, watch game reviewer NateWantsToBattle for his own experience, and just revel in the beautiful graphics. We’re a long way from Type!

Related Content:

William S. Burroughs Teaches a Free Course on Creative Reading and Writing (1979)

The Internet Arcade Lets You Play 900 Vintage Video Games in Your Web Browser (Free)

Seven Tips From Ernest Hemingway on How to Write Fiction

George Plimpton, Paris Review Founder, Pitches 1980s Video Games for the Mattel Intellivision

Ted Mills is a freelance writer on the arts who currently hosts the FunkZone Podcast. You can also follow him on Twitter at @tedmills, read his other arts writing at tedmills.com and/or watch his films here.