A joint operation of five participating countries and the European Space Agency, the International Space Station is an enormous achievement of human cooperation across ideological and national boundaries. Generations of people born in the nineties and beyond will have grown up with the ISS as a symbol of the triumph of STEM education and decades of space travel and research. What they will not have experienced is something that seems almost fundamental to the cultural and political landscape of the Boomers and Gen Xers—the Cold War space race. But it is worth noting that while Russia is one of the most prominent partners in ISS operations, current Communist republic China has virtually no presence on it at all.

But this does not mean that China has been absent from the space race—quite the contrary. While it seems to those of us who witnessed the exciting interstellar competition between superpowers that the only players were the big two, the Chinese entered the race in the 1960s and launched their first satellite in 1970. This craft, writes space history enthusiast Sven Grahn, “would lead to China being a major player in the commercial space field.”

Since its launch into orbit, the satellite has continuously broadcast a song called Dong Fang Hong, a eulogy for Mao Zedong (which “effectively replaced the National Anthem” during the Cultural Revolution—hear the broadcast here). The satellite, now referred to, after its song, as DFH‑1 (or CHINA‑1), marked a significant breakthrough for the Chinese space program, spearheaded by rocket engineer Qian Xuesen, who had been previously expelled from the Jet Propulsion Lab in Pasadena for suspected Communist sympathies.

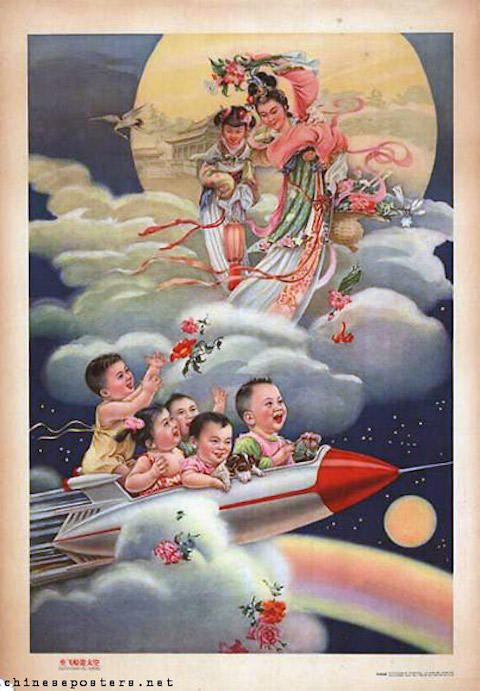

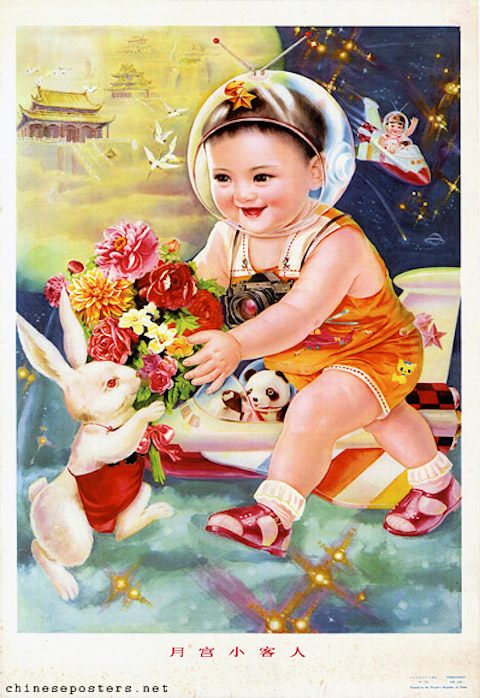

Before DFH‑1, the national imagination was primed for the prospect of Chinese space flight by images like the poster just above, titled “Roaming outer space in an airship,” and designed by Zhang Ruiheng in 1962. This striking piece of work comes to us from Chinese Posters, a compendium of images of “propaganda, politics, history, art.” Images like this one and that of a Chinese taikonaut at the top—“Bringing his playmates to the stars”—from 1980, appropriate imagery from the traditional nianhua, or New Years picture.

This fanciful style, which “catered to the tastes and beliefs in the countryside,” became the “most important influence on the propaganda posters produced by the Chinese Communist Party,” who began using it in the 1940s. The poster above, “Little guests in the Moon Palace,” dates from the early 1970s, after the launch of DFH‑1 and its sister satellite SJ‑I (CHINA‑2).

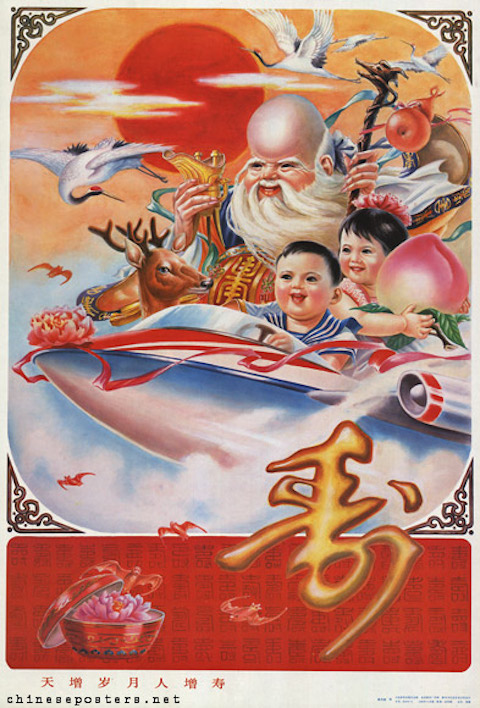

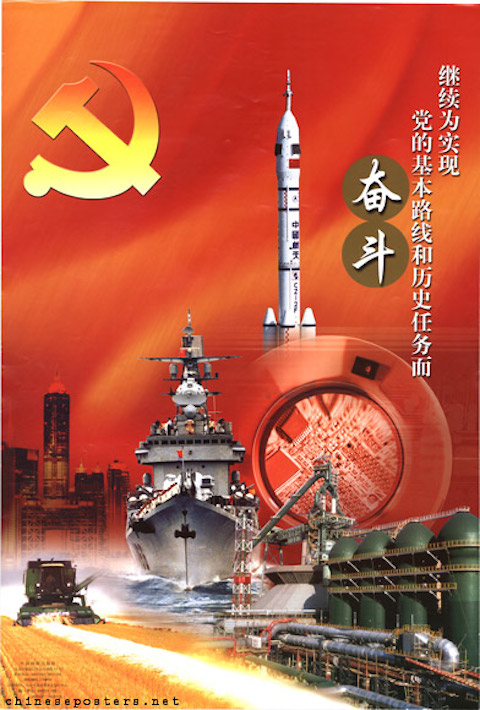

As you can see from the 1989 poster above—“Heaven increases the years, man gets older”—the CCP continued to use the nianhua style well into the eighties, but in the following decades, they began to move away from it and toward more militaristic imagery, like that in the image below from 2002. With different colors and symbols, it would look right at home on the wall of an armed forces recruiting station in any small town, U.S.A.

Like many U.S. advocates for space travel and exploration, such as the increasingly visible Neil deGrasse Tyson, the CCP has used space as a means of promoting scientific literacy. In the poster below, “Uphold science, eradicate superstition,” space imagery is used to bring much-persecuted Falon Gong adherents “back into the fold” and to oppose science to religious superstition.

Although some of the imagery may suggest otherwise, the Chinese space program has developed along similar lines as the U.S.’s, and has been put to similar uses. These include the use of space exploration as a means of unifying nationalist sentiment, driving support for science and technology funding and research, and pushing a vision of scientific progress as the national ethos. In 2012, the same year that Sally Ride—first American woman in space—passed away, China began selecting its first female taikonaut, making their space program a venue for increasing gender equality as well.

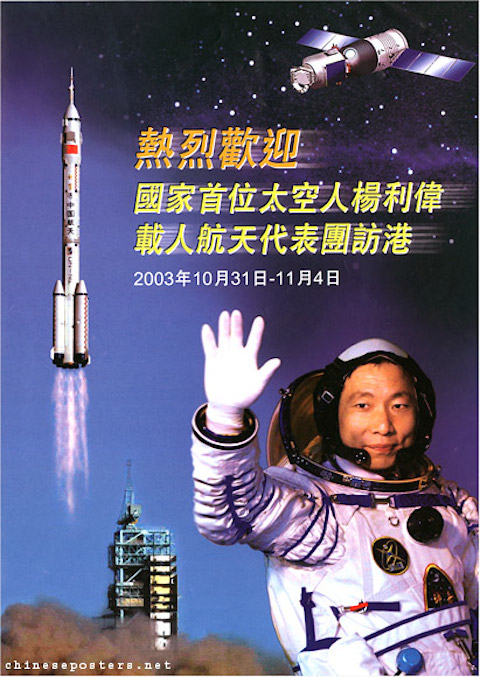

It was only very recently that the Chinese space program successfully completed its first manned mission, sending its first taikonaut, Yang Liewei, abord the Shenzhou 5 in a low earth orbit mission. Although the achievement—as you can see in the poster above commemorating a visit of the taikonaut to Hong Kong—marked a moment of significant national pride, there was one encouraging sign for the future of international cooperation: though you cannot see it in the photo, Yang wore the flag of the United Nations in addition to that of the People’s Republic of China.

See more of these fascinating works of propaganda at Chinese Posters

Related Content:

Soviet Artists Envision a Communist Utopia in Outer Space

Astronaut Sunita Williams Gives an Extensive Tour of the International Space Station

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness