A hundred years before Sigmund Freud used himself as a test subject for his experiments with cocaine, another scientist, Humphry Davy, English chemist and future president of the Royal Society, began “a very radical bout of self experimentation to determine the effects of” another drug—nitrous oxide, better known as “laughing gas.” Davy’s findings — Researches, Chemical and Philosophical Chiefly Concerning Nitrous Oxide, or Diphlogisticated Nitrous Air, And Its Respiration By Humphry Davy—published in 1800, come to us via The Public Domain Review, who describe the 1799 experiments thus:

With his assistant Dr. Kinglake, he would heat crystals of ammonium nitrate, collect the gas released in a green oiled-silk bag, pass it through water vapour to remove impurities and then inhale it through a mouthpiece. The effects were superb. Of these first experiments he described giddiness, flushed cheeks, intense pleasure, and “sublime emotion connected with highly vivid ideas.”

Though we don’t typically think of nitrous oxide as an addictive substance, like Freud’s experiments, Davy’s progressed rapidly from curiosity to recreation: “He began to take the gas outside of laboratory conditions, returning alone for solitary sessions in the dark, inhaling huge amounts, ‘occupied only by an ideal existence,’ and also after drinking in the evening.” Fortunately for us, however, also like Freud, Davy “continued to be meticulous in his scientific records throughout.” Eventually, the twenty-year-old Davy constructed an “air-tight breathing box.” Sealing himself inside, writes Mike Jay, Davy had Dr. Kinglake “release twenty quarts of nitrous oxide every five minutes for as long as he could retain consciousness.”

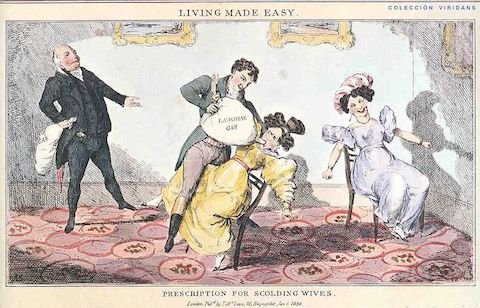

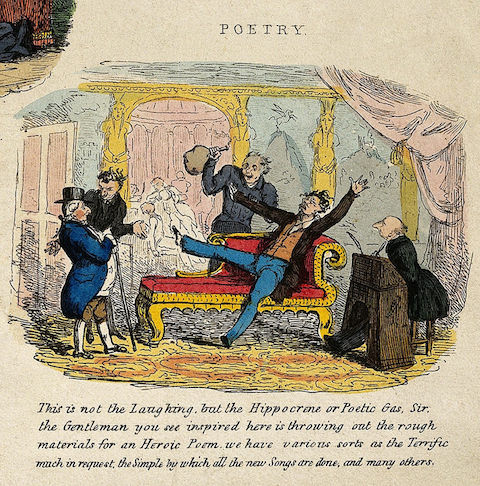

Also, like Freud’s use of cocaine, Davy’s research briefly led to a faddish recreational use of the drug, well into the early part of the nineteenth century, as you can see in the caricatures at the top and below, from 1830 and 1829, respectively. But despite what these humorous images suggest, “laughing gas” became known not only as a party drug, but also as a means of achieving heightened states of consciousness conducive to philosophical reflection and poetic creation (hence the “Philosophical” reference in the title of Davy’s research). During his own experiences “under the influence of the largest does of nitrous oxide anyone had ever taken,” Davy “’lost all connection with external things,’ and entered a self-enveloping realm of the senses,” writes Jay, finding himself “‘in a world of newly connected and modified ideas,’ where he could theorise without limits and make new discoveries at will.”

The appeal of this state to a scientist may be obvious, and to a poet even more so. Davy’s friend Robert Southey, the future Poet Laureate, became “as effusive” as Davy after taking the gas, exclaiming, “the atmosphere of the highest of all possible heavens must be composed of this gas.” In addition to Southey, Davy’s “freewheeling program of consciousness expansion… co-opted some of the most remarkable figures of his day”—including Samuel Taylor Coleridge, who is already well-known for finding some of his poetic inspiration under the influence of opium. Coleridge at the time had just published to great acclaim The Lyrical Ballads with William Wordsworth and had returned from a brief sojourn in Germany, where he had become heavily influenced by the German Idealist philosophy of Immanuel Kant and Friedrich Schelling.

Coleridge, who was “captivated by the young chemist” Davy, described his experience of taking nitrous oxide for the first time in very precise terms, avoiding the “extravagant metaphors” others tended to rely on. He recalled the sensations as resembling “that which I remember once to have experienced after returning from the snow into a warm room,” and, in a later trial, said he was “more violently acted upon” and that “towards the last I could not avoid, nor felt any wish to avoid, beating the ground with my feet; and after the mouthpiece was removed, I remained for a few seconds motionless, in great ecstacy.” Under the influence of both nitrous oxide and philosophical metaphysics, Coleridge had come to believe “the material world only an illusion projected by” the mind.

Davy, who fully endorsed this view, claiming “nothing exists but thoughts,” brought his “chaotic mélange of hedonism, heroism, poetry and philosophy” to heel in the “coherent and powerful” 580-page monograph above, which makes the case for laughing gas’s scientific and poetic worth. The report, writes Jay, combines “two mutually unintelligible languages—organic chemistry and subjective experience—to create a groundbreaking hybrid, a poetic science.” Like Freud’s use of cocaine or Timothy Leary’s experiments with LSD decades later, Davy’s experiments further demonstrate, perhaps, that the few times the sciences, philosophy, and poetry communicate with each other, it’s generally under the influence of mind-altering substances.

For more on Davy and nineteenth century England’s fascination with laughing gas, see Mike Jay’s Public Domain Review essay here and read this New York Review of Books article on his book-length treatment of the subject, The Atmosphere of Heaven: The Unnatural Experiments of Dr. Beddoes and His Sons of Genius.

Related Content:

How a Young Sigmund Freud Researched & Got Addicted to Cocaine, the New “Miracle Drug,” in 1894

Beyond Timothy Leary: 2002 Film Revisits History of LSD

Carl Sagan Extols the Virtues of Cannabis (1969)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness