The great capitalist game of Monopoly was first marketed by Parker Brothers back in February 1935, right in the middle of the Great Depression. Even during hard times, Americans could still imagine amassing a fortune and securing a monopoly on the real estate market. When it comes to making money, Americans never run out of optimism and hope.

Monopoly didn’t really begin, however, in 1935. And if you trace back the origins of the game, you’ll encounter an ironic, curious tale. The story goes like this: Elizabeth (Lizzie) J. Magie Phillips (1866–1948), a disciple of the progressive era economist Henry George, created the prototype for Monopoly in 1903. And she did so with the goal of illustrating the problems associated with concentrating land in private monopolies.

As Mary Pilon, the author of the new book The Monopolists: Obsession, Fury, and the Scandal Behind the World’s Favorite Board Game, recently explained in The New York Times, the original game — The Landlord’s Game — came with two sets of rules: “an anti-monopolist set in which all were rewarded when wealth was created, and a monopolist set in which the goal was to create monopolies and crush opponents.” Phillips’ approach, Pilon adds, “was a teaching tool meant to demonstrate that the first set of rules was morally superior.” In other words, the original game of Monopoly was created as a critique of monopolies — something the trust- and monopoly-busting president, Theodore Roosevelt, could relate to.

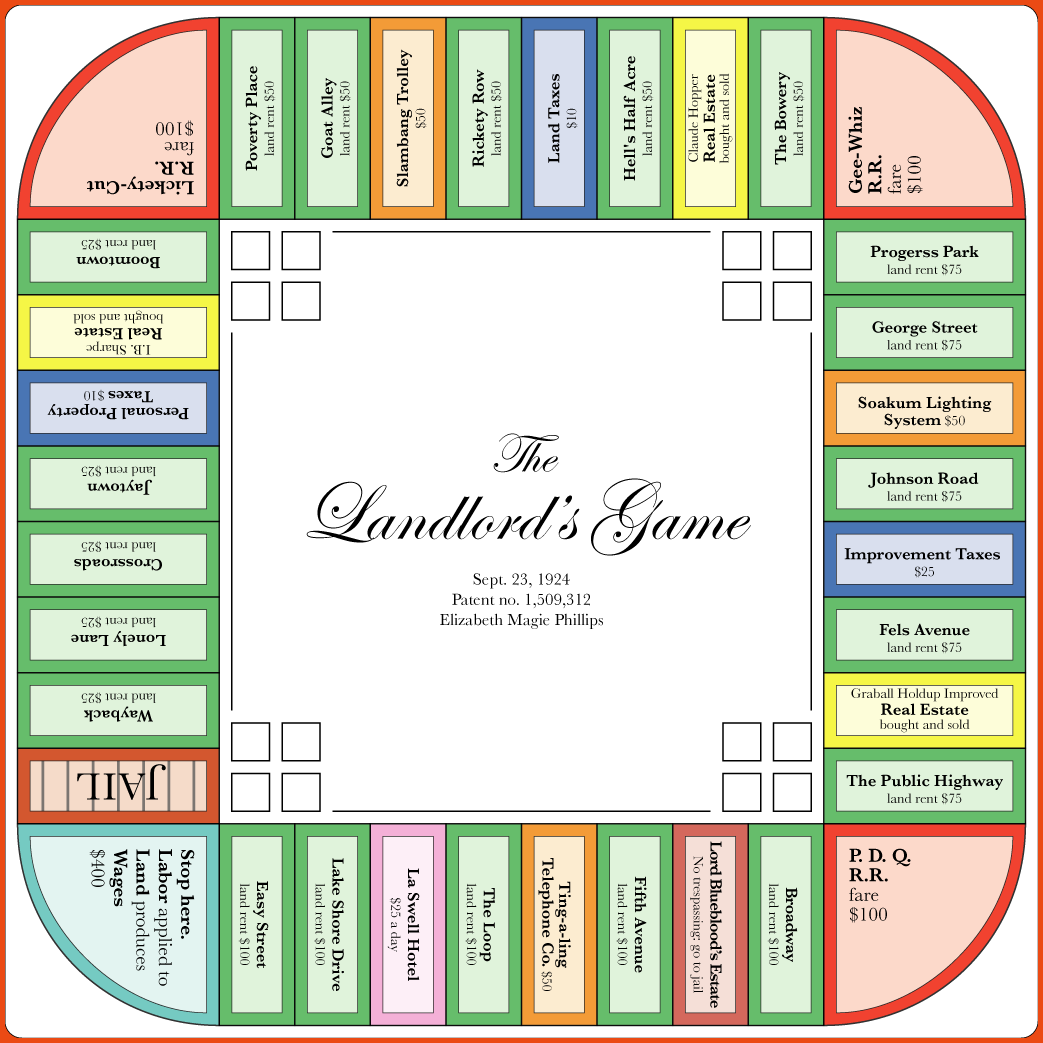

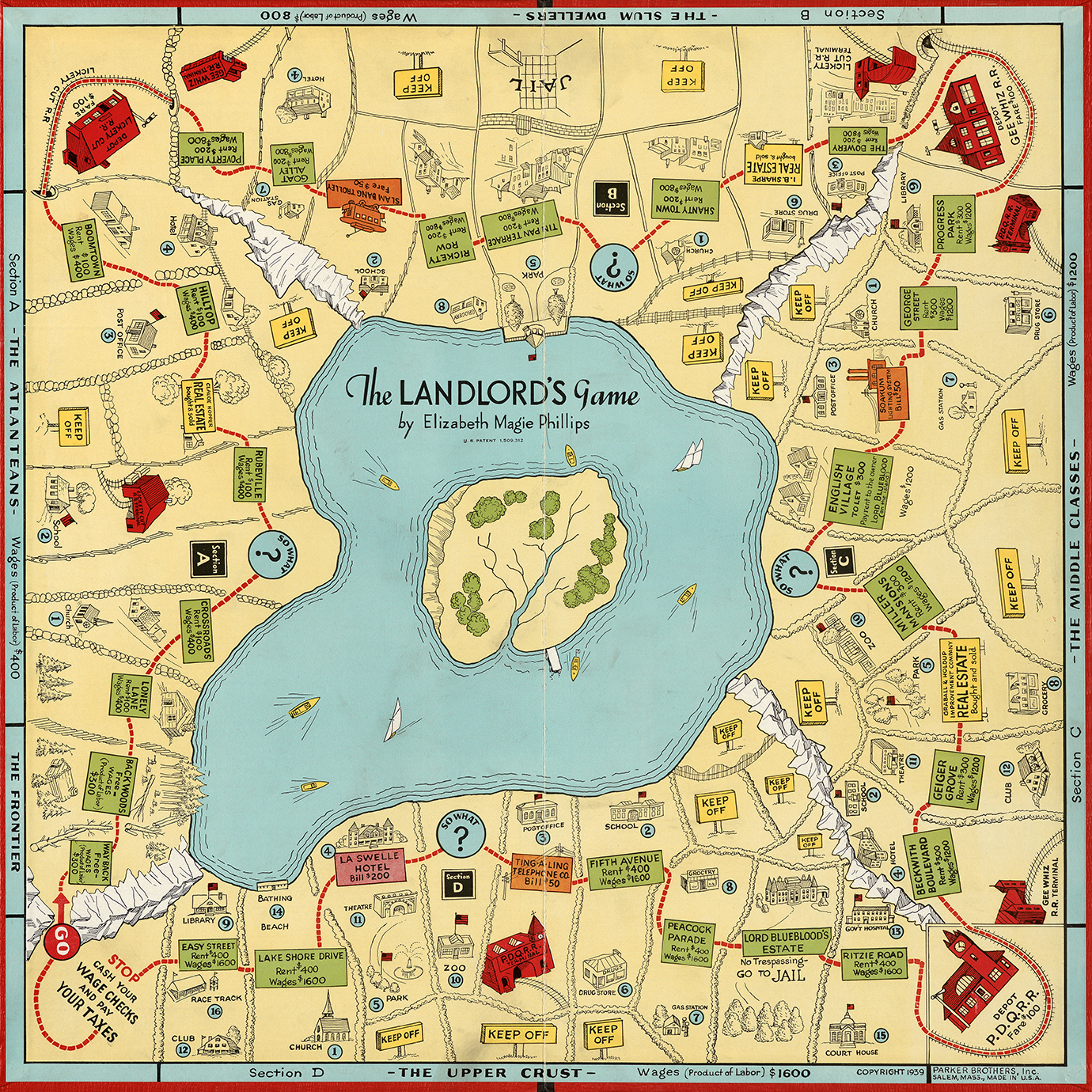

Patented in 1904 and self-published in 1906, The Landlord’s Game featured “play money and deeds and properties that could be bought and sold. Players borrowed money, either from the bank or from each other, and they had to pay taxes,” Pilon writes in her new book.

The Landlord’s Game also had the look & feel of the game the Parker Brothers would eventually bastardize and make famous. Above, you can see an image from the patent Philips filed in 1904 (top), and another image from the marketed game.

Magie Philips never got credit or residuals from the Parker Brothers’ game. Instead, a fellow named Charles Darrow came along and drafted his own version of the game, tweaked the design, called it Monopoly (see the earliest version here), slapped a copyright on the packaging with his name, and then sold the game to Parker Brothers for a reported $7,000, plus residuals. He eventually made millions.

As they like to say in the US, it’s just business.

For more on the origins of Monopoly, read Mary Pilon’s piece in The Times.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. Or follow our posts on Threads, Facebook, BlueSky or Mastodon.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content:

Henry Rollins: Education is the Cure to “Disaster Capitalism”

Free Online Economics Courses

Andrei Tarkovsky’s Masterpiece Stalker Gets Adapted into a Video Game