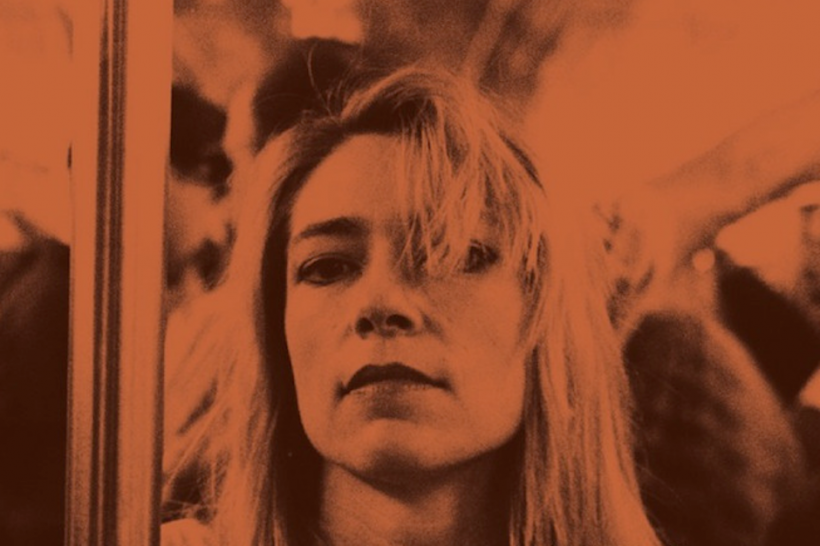

At home I often watch EBS, essentially Korea’s equivalent of PBS, which often airs short interstitial segments drawn in sand to fill the time between programs. Only recently have I learned that sand actually has a genuine history as a medium for animation, one that has produced a work as striking as Caroline Leaf’s The Metamorphosis of Mr. Samsa back in 1977. Astute (or even not-very-astute) Kafka fans will recognize this as an adaptation of The Metamorphosis, far and away the writer’s best-known story, in which the young salesman Gregor Samsa wakes up transformed into a giant bug. Find it in our Free Audio Books and Free eBooks collections.

We see this bug writhing his way out of bed before we see any other action in Leaf’s ten-minute sand short, whose (yes) ever-shifting visual texture lends itself well to the theme of the tale. Not that this convergence of form and substance came easily: “What makes [Leaf’s] work stand out is the control of the material,” writes Johnny Chew, About Tech’s animation expert. “The Metamorphosis of Mr. Samsa is an awesome short film on its own, and a great adaptation of the Kafka work, but when you consider the style in which it was made and the control that would have to go into each frame, it’s unbelievable.”

“The medium of animation, and specifically certain animated techniques, offer an ability to faithfully reproduce in part both the content and the perceptual experience of a literary work,” writes Geoffrey Beatty in his paper “The Problem of Adaptation Solved!.” In it, he quotes the animator on why she chose this particular story: “ ‘Kafka’s stories give this kind of room to invent,’ she says. This was an important value for Leaf as she was establishing a body of work based on a unique visual approach. The Metamorphosis, suggested to her by a friend and mentor, was a good fit, as her own ‘black and white sand images had the potential to have a Kafka-esque feel – dark and mysterious.’ ”

Any worthwhile artistic medium imposes limitations — and sand, as you’d imagine, imposes some pretty serious ones. Working with it, Leaf “would not be able to create highly detailed images [such as] the festering wound on Gregor’s back or his overall deterioration and decay. However, this limitation was not necessarily a problem. ‘I think that the limitations of drawing in sand, the simplifications that it requires, made me inventive in the storytelling in the ways I mentioned above. Sand forced me to adapt the story to sand, which is interesting.’ ”

Those readers who apply the word “Kafkan” to any pointlessly difficult task (like, say, getting out the door to work when you’ve become a giant bug) might also use it to describe Leaf’s labor-intensive sand animation process. But unlike a truly Kafkan labor, Leaf’s generated a result — and a delightful one at that. Now if only the next generation of sand animators would step foward to adapt the rest of Kafka’s oeuvre. Maybe we could interest PBS in airing it?

Find more literary animations in our collection, 4,000+ Free Movies Online: Great Classics, Indies, Noir, Westerns, Documentaries & More.

Related Content:

Watch Franz Kafka, the Wonderful Animated Film by Piotr Dumala

The Art of Franz Kafka: Drawings from 1907–1917

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture as well as the video series The City in Cinema and writes essays on cities, language, Asia, and men’s style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.