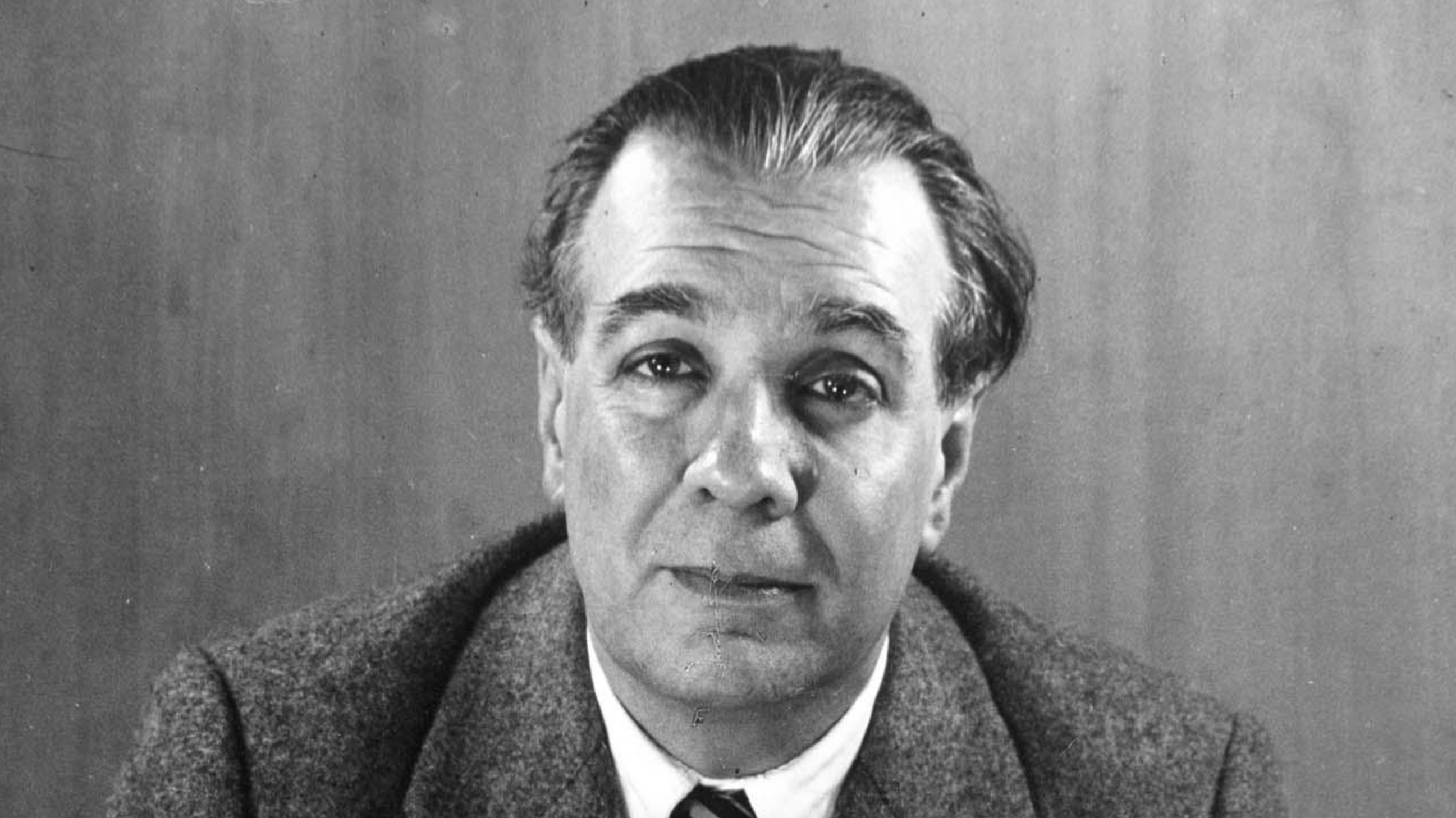

“Jorge Luis Borges 1951, by Grete Stern.” Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Over the years the recommendation robots of Amazon and other online services seem to be usurping the role of the librarian. I do not know if this is ultimately good or bad—we may see in the future artificially intelligent librarians emerge from the web, personal literary assistants with impeccable taste and sensitivity. But at present, I find something lacking in online curation cultivated by algorithms. (I have a similar nostalgia for the bygone video store clerk.) Yes, customers who bought this book also bought others I might like, but what, tell me, would a genuine reader recommend?

A reader, say, like that arch reader Jorge Luis Borges, “one of the most well read men in history,” writes Grant Munroe at The Rumpus. Part of the thrill of discovering Borges resides in discovering all of the books he loved, both real and imaginary. The author always points to his sources. Borges, after all, “presented the genius of Pierre Menard, author of the Quixote [a story about writing as scrupulously faithful rewriting] by first carefully enumerating each book found in Menard’s personal library.” Borges himself, some readers may know, wrote the bulk of the short stories for which he’s known while working at a library in Buenos Aires, a job he described in his 1970 essay “Autobiographical Notes” as “nine solid years of unhappiness.”

Although he disliked the bureaucratic boredom of library work, Borges was better suited than perhaps anyone for a curatorial role. Given this reputation, Borges was asked more than once to select his favorite novels and stories for published anthologies. One such multi-volume project, titled Personal Library, saw Borges selecting 74 titles for an Argentine publisher between 1985 and his death in 1988. In another, Borges chose “a list of authors,” Monroe writes, “whose works were selected to fill 33 volumes in The Library of Babel, a 1979 Spanish language anthology of fantastic literature edited by Borges, named after his earlier story by the same name.”

Monroe tracked down all of the titles Borges chose for the eclectic anthology, “a fun, brilliant, polyglot collection” that includes a great many of the author’s perennial favorites, many of which you’ll recognize from their mentions in his fiction and essays. Below, we reproduce Monroe’s reconstruction of the 33 Library of Babel volumes, with links to those works available free online. Unfortunately, many of these stories are not available in translation. Others, such as those of Leon Bloy, have just become available in English since Monroe’s 2009 article. Thanks to his diligence, we can enjoy having Jorge Luis Borges as our personal librarian.

The Library of Babel

(Note: The titles of all stories currently without a proper translation into English have been left in their original language.)

(Also note: All stories marked with [c] are still protected by US copyright law. Only residents of the UK and Australia can legally click on the hyperlink provided.)

- Jack London, The Concentric Deaths

“The Minions of Midas”

“The Shadow and the Flash”

“Lost Face”

“The House of Mapuhi”

“The Law of Life”

- Jorge Luis Borges, August 26, 1983

(All but the last three articles are available in Penguin’s Borges: The Collected Fictions.)

“August 26, 1983″

“The Rose of Peracelsus”

“Blue Tigers”

“Shakespeare’s Memory”

An Interview with Borges, with Maria Esther Vasquez

A Chronology of J.L. Borges’ Life, from Siruela Magazine

The Ruler and Labyrinth: An Approximation of J.L Borges’ Bibliography, by Fernandez Ferrer

- Gustav Meyrink, Cardinal Napellus[ii]

“Der Kardinal Napellus”

“J.H. Obereits Besuch bei den Zeitegeln”

“Der Vier Mondbrüder”

- Léon Bloy, Disagreeable Tales

[All available in a translation published just this year]

“La Taie d’Argent”

“Les Captifs de Longjumeau”

“Une Idée Médiocre”

“Une Martyre”

“La Plus Belle Trouvaille de Caïn”

“On n’est pas Parfait”

“La Religion de M. Pleur”

“Terrible Châtiment d’un Dentiste”

“La Tisane”

“Tout Ce Que Tu Voudras!”

“La Dernière Cuite”

“Le Vieux de la Maison”

- Giovanni Papini, The Mirror That Fled

“Il Giorno Non Restituito”

“Due Immagini in una Vasca”

“Lo Specchio che Fugge”

“Storia Completamente Assurda”

“Il Mendicante di Anime”

“Una Morte Mentale”

“Non Voglio Più Essere Ciò che Sono”

“Chi Sei?”

“Il Suicida Sostituto”

“L’ultima Visita del Gentiluomo Malato”

- Oscar Wilde, Lord Arthur Savile’s Crime

“Lord Arthur Savile’s Crime”

“The Canterville Ghost”

“The Selfish Giant”

“The Happy Prince”

“The Nightingale and the Rose”

- Villiers de L’Isle-Adam, El Convidado de las Últimas Festivas

(Used copies of the 1985 Oxford U. Press translation of Cruel Tales (the collection in which these stories are published) are available online.)

“L’Aventure de Tsé-i-la”

“Le Convive des Dernières Fêtes”

“A Torture By Hope” [trans. 1891]

“La Reine Ysabeau”

“Sombre Récit Conteur Plus Sombre”

“L’Enjeu”

“Véra”

- Pedro Antonio de Alarcón, El Amigo de la Muerte

“El Amigo de la Muerte” [or “The Strange Friend of Tito Gil”]

“The Tall Woman”

- Herman Melville, Bartleby the Scrivener

“Bartleby, the Scrivener: A Story of Wall-Street”

- William Beckford, Vathek

Vathek, a novella.

- H.G. Wells, The Door in the Wall

“The Plattner Story”

“The Story of Late Mr. Elvesham”

“The Crystal Egg”

“The Country of the Blind”

“The Door in the Wall”

- Pu Songling, The Tiger Guest [iii]

“The Buddhist Priest of Ch’ang-Ch’ing”

“In the Infernal Regions”

“The Magic Mirror”

“A Supernatural Wife”

“Examination for the Post of Guardian Angel”

“The Man Who Was Changed into a Crow”

“The Tiger Guest”

“Judge Lu”

“The Painted Skin”

“The Stream of Cash”

“The Invisible Priest”

“The Magic Path”

“The Wolf Dream”

“Dreaming Honors”

“The Tiger of Chao-Ch’ëng”

“Taking Revenge”

- Arthur Machen, The Shining Pyramid

“The Novel of the Black Seal”

“The Novel of the White Powder”

“The Shining Pyramid”

- Robert Louis Stevenson, The Isle of Voices [iv]

“The Bottle Imp”

“The Isle of Voices”

“Thrawn Janet”

“Markheim”

- G.K. Chesterton, The Eye of Apollo

“The Duel of Dr Hirsch”

“The Queer Feet”

“The Honor of Israel Gow”

“The Eye of Apollo”

“The Three Horsemen of the Apocalypse” [c]

- Jacques Cazotte, The Devil in Love

(A new translation is available from Dedalus Press of the UK.)

The Devil in Love, a novella.

“Jacquez Cazotte,” an essay by Gerard de Nerval

- Franz Kafka, The Vulture

(While I’ve provided links to online translations, they’re somewhat suspect; probably better to check the Complete Short Stories.)

“The Hunger Artist”

“First Sorrow” [or “The Trapeze Artist”]

“The Vulture”

“A Common Confusion”

“Jackals and Arabs”

“The Great Wall of China”

“The City Coat of Arms”

“A Report to the Academy”

“Eleven Sons”

“Prometheus”

- Edgar Allan Poe, The Purloined Letter

“The Purloined Letter”

“Ms. Found in a Bottle”

“The Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar”

“The Man in the Crowd”

“The Pit and the Pendulum”

- Leopoldo Lugones, The Pillar of Salt

(A new translation of Lugones’ stories, published by The Library of Latin America, is available at Powell’s.)

“The Pillar of Salt”

“Grandmother Julieta”

“The Horses of Abdera”

“An Inexplicable Phenomenon”

“Francesca”

“Rain of Fire: An Account of the Immolation of Gomorra”

- Rudyard Kipling, The Wish House

(All the copyrighted stories are from Kipling’s Debits and Credits. They should be available in any thorough collection of his short fiction.)

“The Wish House” [c]

“A Sahib’s War”

“The Gardener” [c]

“The Madonna of the Trenches” [c]

“The Eye of Allah” [c]

- The Thousand and One Nights, According to Galland

“Abdula, the Blind Beggar” [trans. 1811]

“Alladin’s Lamp” [ibid]

- The Thousand and One Nights, According to Burton

“King Sinbad and His Falcon”

“The Adventures of Bululkia”

“The City of Brass”

“Tale of the Queen and the Serpent”

“Tale of the Husband and the Parrot”

“Tale of the Jewish Doctor”

“Tale of the Ensorcelled Prince”

“Tale of the Prince and the Ogres”

“Tale of the Wizir and the Wise Duban”

“The Fisherman and the Genii”

- Henry James, The Friends of the Friends

“The Friends of the Friends”

“The Abasement of the Northmores”

“Owen Wingrave”

“The Private Life”

- Voltaire, Micromegas

(A contemporary translation of these stories is available at Powell’s.)

“The Black and the White”

“The Two Conforters”

“The History of the Travels of Scaramentado”

“Memnon the Philosopher”

“Micromegas”

“The Princess of Babylon”

- Charles Hinton, Scientific Romances

“A Plane World”

“What is the Fourth Dimension?”

“The Persian King”

- Nathaniel Hawthorne, The Great Stone Face

“Mr. Higginbotham’s Catastrophe”

“The Great Stone Face”

“Earth’s Holocaust”

“The Minister’s Black Veil”

“Wakefield”

- Lord Dunsany, The Country of Yann

“Where the Tides Ebb and Flow”

“The Sword and the Idol”

“Carcassonne”

“Idle Days on the Yann”

“The Field”

“The Beggars”

“The Bureau d’Echange de Maux”

“A Night at an Inn”

- Saki, The Reticence of Lady Anne

“The Story-Teller”

“The Lumber Room”

“Gabriel-Ernest”

“Tobermory”

“The Background” [translated as “El Marco” (or “The Frame”)]

“The Unrest Cure”

“The Interlopers”

“Quail Seed”

“The Peace of Mowsle Barton”

“The Open Window”

“The Reticence of Lady Anne”

“Sredni Vashtar”

- Russian Tales

“Lazarus,” Leonid Andreyev

“The Crocodile,” Fydor Doestoevsky

“The Death of Ivan Illitch,” Leo Tolstoy

- Argentinean Tales

“El Calamar Opta por su Tinta,” Adolfo Bioy Casares

“Yzur,” Leopoldo Leones [See above.]

“A House Taken Over,” Julio Cortazar

“La Galera,” Manuel Mujica Láinez

“Los Objectos,” Sylvina Decampo

“El Profesor de Ajedrez,” Federico Peltzer

“Pudo Haberme Ocurrido,” Manuel Peyrou

“El Elegido,” Maria Esther Vasquez

- J.L. Borges and Adolfo Bioy Casares, New Stories of H. Bustos Domecq

(Available at Amazon.com.)

- The Book of Dreams (A Collection of Recounted Dreams)

List of Authors: Francisco de Quevedo y Villegas, Alexandra David-Néel, Alfonso X, Alfred de Vigny, Aloysius Bertrand, Antonio Machado, Bernabé Cobo, F. Sarmiento, Eliseo Díaz, Francisco Acevedo, François Rabelais, Franz Kafka, Friedrich Nietzsche, Gastón Padilla, Giuseppe Ungaretti, Gottfried Keller, H. Desvignes Doolittle, Herbert Allen Giles, Herodotus, H. Garro, Horace, Ibrahim Zahim [Ibrahim Bin Adham], James G. Frazer, Jorge Alberto Ferrando, Jorge Luis Borges, José Ferrater Mora, José María Eça de Queiroz, Joseph Addison, Juan José Arreola, Lewis Carroll, Lao Tzu, Louis Aragon, Luigi Pirandello, Luis de Góngora, Mircea Eliade, Mohammad Mossadegh, Nemer ibn el Barud [no Wiki entry; see Amazon comment field], O. Henry, Otto von Bismarck, Paul Groussac, Plato, Plutarch, Rabbi Nissim ben Reuven, Raymond de Becker, Rodericus Bartius, Roy Bartholomew, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Sebastián de Covarrubias Orozco, Thornton Wilder, Lucretius, Tsao Hsue Kin [Cao Xueqin], Ward Hill Lamon, William Butler Yeats, Wu Cheng’en, Giovanni Papini, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Charles Baudelaire

- Borges A to Z (A Compilation)

Related Content:

Jorge Luis Borges Selects 74 Books for Your Personal Library

Jorge Luis Borges’ 1967–8 Norton Lectures On Poetry (And Everything Else Literary)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness