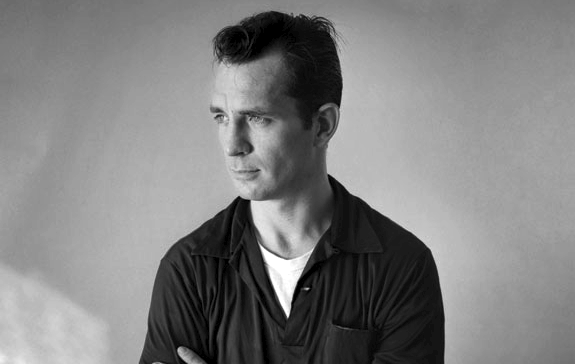

Image by Tom Palumbo, via Wikimedia Commons

At the epicenter of three explosive forces in 1950s America—the birth of Bebop, the spread of Buddhism through the counterculture, and Beat revolutionizing of poetry and prose—sat Jack Kerouac, though I don’t picture him ever sitting for very long. The rhythms that moved through him, through his verse and prose, are too fluid to come to rest. At the end of his life he sat… and drank, a mostly spent force.

But in his prime, Kerouac was always on the move, over highways on those legendary road trips, or his fingers flying over the typewriter’s keys as he banged out the scroll manuscript of On the Road in three feverish weeks (so he said). After the publication of On the Road, Kerouac “became a celebrity,” says Steve Allen in introduction to the Beat writer on a 1959 appearance, “partly because he’d written a powerful and successful book, but partly because he seemed to be the embodiment of this new generation.”

After a little back-and-forth, Allen lets Kerouac do what he always did so well, whether on television or on record—embody the rhythms of his writing in his voice, his phrasing always musical, whether he read over jazz hot or cool or over meditative silence. He did a lot of both, recording with Allen and many other jazzmen, and “experimenting with a home reel-to-reel system, taping himself to see whether his spontaneous prose outbursts had the musical rhythms F. Scott Fitzgerald considered the hallmark of all great writing.” So writes historian David Brinkley in the liner notes (remember those?) to the compilation album Jack Kerouac Reads On the Road, a rare collection of haunting poetry readings, playful crooning, and experiments with voice and music. Brinkley describes how Kerouac, the French Canadian from Lowell, Massachusetts, developed his “bop ear” by hanging out at Minton’s Playhouse in Harlem in the 40s, watching Thelonious Monk, Charlie Parker, and Dizzy Gillespie invent what he called a “goofy new sound.”

The sound stayed with him, as he turned his immersion into American literary and musical counterculture into On the Road, The Subterraneans, The Dharma Bums, etc, and throughout all the writing, there was the music of his reading, captured on the albums Poetry for the Beat Generation with Steve Allen, Blues and Haikus with Al Cohn and Zoot Sims—both in 1959—and, the following year, Readings by Jack Kerouac on the Beat Generation. Kerouac’s reading style did not come only from his internalization of bebop rhythms, however, but also from “the discovery of the extraordinary spoken-word albums of poets Langston Hughes, Carl Sandberg, and Dylan Thomas,” Brinkley tells us. The writer became “convinced that prose should be read aloud in public, as it had been in Homer’s Greece and Shakespeare’s England.” The albums he recorded and released in his lifetime bear out this conviction and explore “the possibilities of combining jazz and spontaneous verse.”

These records became very difficult to find for many years, but you can now purchase an omnibus CD at a reasonable price (vinyl will set you back a couple hundred bucks). Alternately, you can stream all three Kerouac albums free on Spotify, above in chronological order of release. If you don’t have Spotify, you can easily download the software here. And if you’d rather hear Kerouac’s readings on CD or on the original vinyl medium, that’s cool too. However you experience these readings, you should, at some point, experience them. Like all the very best poetry, Kerouac’s work is most alive when read aloud, and most especially when read aloud by Kerouac himself.

Related Content:

Download 55 Free Online Literature Courses: From Dante and Milton to Kerouac and Tolkien

Jack Kerouac’s 30 Beliefs and Techniques For Writing Modern Prose

Jack Kerouac Lists 9 Essentials for Writing Spontaneous Prose

The First Recording of Allen Ginsberg Reading “Howl” (1956)

Watch Langston Hughes Read Poetry from His First Collection, The Weary Blues (1958)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness