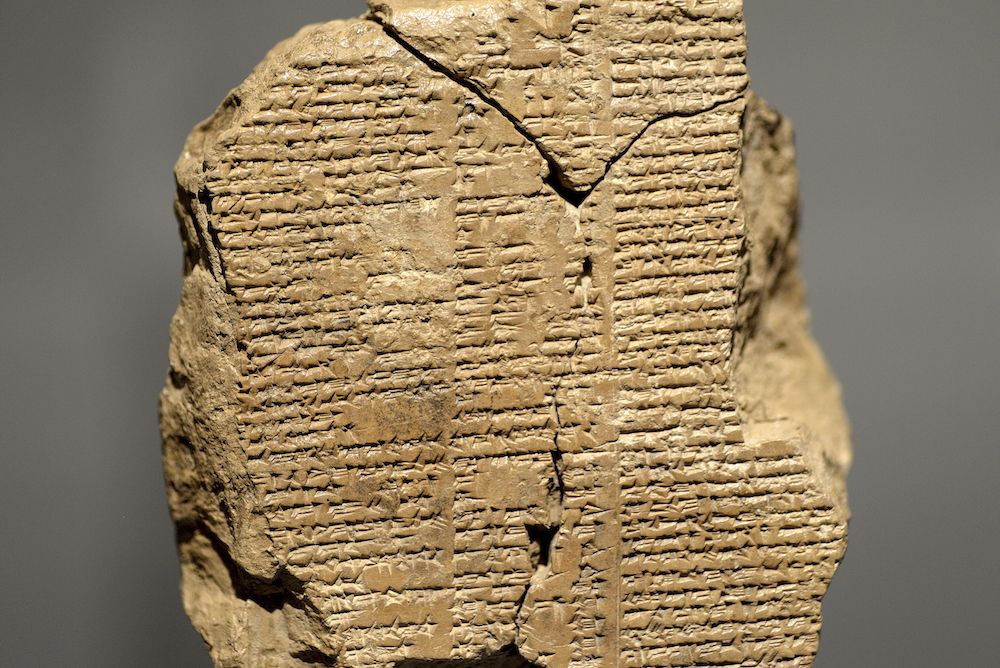

Creative Commons image by Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin

When one enters the world of The Epic of Gilgamesh, the oldest epic poem we know of, one enters a world lost to time. Though its strange gods and customs would have seemed perfectly natural to its inhabitants, the culture of Gilgamesh has so far receded from historical memory that there’s little left with which we might identify. Scholars believe Gilgamesh the demi-god mythological character may have descended from legends (such as a 126-year reign and superhuman strength) told about a historical 5th king of Uruk. Buried under the fantastic stories lies some documentary impulse. On the other hand, Gilgamesh—like all mythology—exists outside of time. Gilgamesh and Enkidu always kill the Bull of Heaven, again and again forever. That, perhaps, is the secret Gilgamesh discovers at the end of his long journey, the secret of Keats’ Grecian Urn: eternal life resides only in works of art.

And perhaps the only way to approach some common understanding of myths as both products of their age and as archetypes in realms of pure thought comes through a deep immersion in their historical languages. In the case of Gilgamesh, that means learning the extraordinarily long-lived Akkadian, a Mesopotamian language that dates from about 2,800 BCE to around 100 CE. In order to do so, archeologists and Assyriologists had to decipher fragments of cuneiform stone tablets like those on which Gilgamesh was discovered. The task proved exceptionally difficult, such that when George Smith announced his translation of the epic’s so-called “Flood Tablet” in 1872, it had lain “undisturbed in the [British] Museum for nearly 20 years,” writes The Telegraph, since “there were so few people in the world able to read ancient cuneiform.”

Cuneiform is not a language, but an alphabet. The script’s wedge-shaped letters (cuneus is Latin for wedge) are formed by impressing a cut reed into soft clay. It was used by speakers of several Near Eastern languages including Sumerian, Akkadian, Urartian and Hittite; depending on the language and date of a given script, its alphabet could consist of many hundreds of letters. If this weren’t challenging enough, cuneiform employs no punctuation (no sentences or paragraphs), it does not separate words, there aren’t any vowels and most tablets are fragmented and eroded.

Nonetheless, Smith, an entirely self-educated scholar, broke the code, and when he discovered the fragment containing a flood narrative that predated the Biblical account by at least 1,000 years, he reportedly “became so animated that, mute with excitement, he began to tear his clothes off.” That story may also be legend, but it is one that captures the passionately obsessive character of George Smith. Thanks to his efforts, those of many other 19th century academics, treasure hunters, and tomb raiders, and modern scholars toiling away at the University of London, we can now hear Gilgamesh read not only in Old Akkadian (the original language), but also later Babylonian dialects, the languages used to record the Code of Hammurabi and a later, more fragmented version of the Gilgamesh epic.

The University of London’s Department of the Languages and Cultures of the Ancient Near East hosts on its website several readings in different scholars’ voices of Gilgamesh, The Epic of Anzu, the Codex Hammurabi and other Babylonian texts. Above, you can hear Karl Hecker read the first 163 lines of Tablet XI of the Standard Akkadian Gilgamesh. These lines tell the story of Utnapishtim, the mythical and literary precursor to the Biblical Noah. So important was the discovery of this flood story that it “challenged literary and biblical scholarship and would help to redefine beliefs about the age of the Earth,” writes The Telegraph. When George Smith made his announcement in 1872, “even the Prime Minister, William Gladstone, was in attendance.” Unfortunately, things did not end well for Smith, but because of his efforts, we can come as close as possible to the sound of Gilgamesh’s world, one that may remind us of a great many modern languages, but that uniquely preserves ancient history and ageless myth.

The University of London site also includes translations and transliterations of the cuneiform writing, from Professor Andrew George’s 2003 The Babylonian Gilgamesh Epic: Introduction, Critical Edition and Cuneiform Texts. Furthermore, there are answers to Frequently Asked Questions, many of which you may yourself be asking, such as “What are Babylonian and Assyrian?”; “Given they are dead, how can one tell how Babylonian and Assyrian were pronounced?”; “Did Babylonian and Assyrian poetry have rhyme and metre, like English poetry?”; and—for those with a desire to enter further into the ancient world of Gilgamesh and other Akkadian, Babylonian, and Assyrian semi-mythical figures—“What if I actually want to learn Babylonian and Assyrian?”

Then, of course, you’ll want to learn about the 20 new lines from Gilgamesh just discovered in Iraq.…

Related Content:

Listen to the Oldest Song in the World: A Sumerian Hymn Written 3,400 Years Ago

Hear Beowulf Read In the Original Old English: How Many Words Do You Recognize?

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness