Imagine if you will that it is the year 4515, and future people slowly begin excavating the musical remains of millennia past. Now add the following wrinkle to this scenario, courtesy of classics scholar Armand D’Angour: “all that survived of the Beatles songs were a few of the lyrics, and all that remained of Mozart and Verdi’s operas were the words and not the music.” Would it be possible to recover the rhythms and melodies from these scraps? Wouldn’t this music be forever lost to history?

Not necessarily, D’Angour tells us; we could “reconstruct the music, rediscover the instruments that played them, and hear the words once again in their proper setting.” Given the inexact, speculative nature of much ancient history, I imagine the reconstructed Beatles might end up sounding nothing like themselves, but then again, now that scholars have begun to recover the music of ancient Greek tragedy from a few fragments of text, surely those future historians could remake “Love Me Do”

Reconstructing Don Giovani might be a little trickier, and that’s often the scale academics like D’Angour are working with, since not only the love-poems of Sappho, but also “the epics of Homer” and “the tragedies of Sophocles and Euripides—were all, originally, music. Dating from around 750 to 400 BC, they were composed to be sung in whole or part to the accompaniment of the lyre, reed-pipes, and percussion instruments.” This much we all likely know to some extent.

D’Angour goes on to describe in detail how scholars like himself use “patterns of long and short syllables” in the surviving verse to determine musical rhythm, and new revelations about ancient Greek vocal notation and tuning to reconstruct ancient melody.

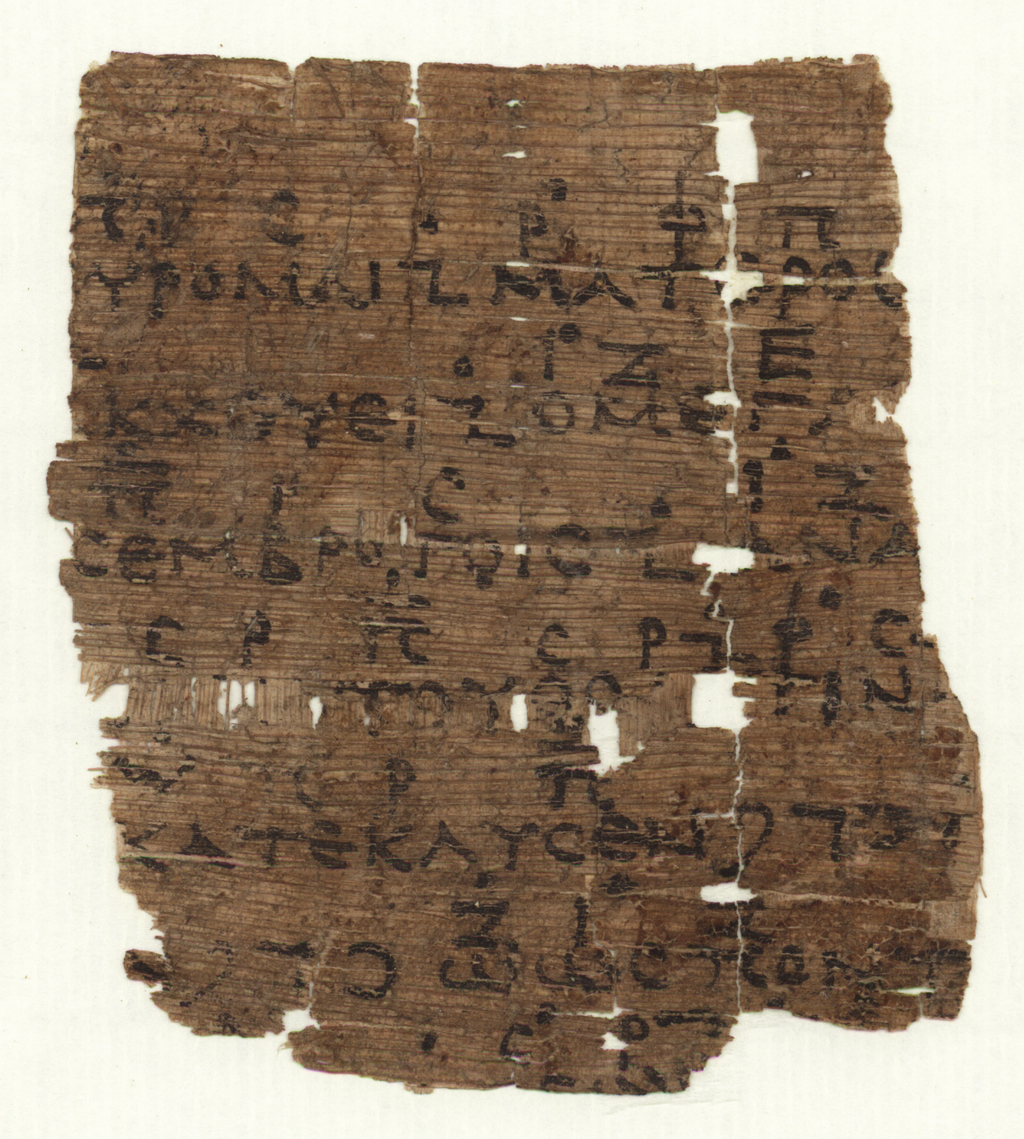

The earliest surviving musical document “preserves a few bars of sung music” from fifth-century tragedian Euripides’ play Orestes. A “notoriously avant-garde composer,” Euripides—scholars presume—“violated the long-held norms of Greek folk-singing by neglecting word-pitch.” You can see the papyrus fragment above, written around 200 BC in Egypt and called “Katolophyromai” after the first word in the “stasimon,” or choral song. Above the words, notice the vocal and instrumental notation scholars have used to reconstruct the music. The lines describe Orestes’ guilt after murdering his mother:

I cry, I cry, your mother’s blood that drives you mad, great happiness in mortals never lasting, but like a sail of swift ship, which a god shook up and plunged it with terrible troubles into the greedy and deadly waves of the sea.

This translation comes from “Greek Reconstructionist Paganism” site Baring the Aegis, who also describe the song’s rhythm, Dochmius, and mode, Lydian, with a helpful explanation for non-specialists of what these terms mean. They also feature the live performance of the stasimon at the top of the post, just one interpretation by Spyros Giasafakis and Evi Stergiou of neofolk band Daemonia Nymphe. Below it, hear another interpretation by Petros Tabouris and Nikos Konstantinopoulos. And just below and at the bottom of the post are two more versions of the ancient song.

Given Euripides’ experimentalism, we can’t expect that this reconstructed song would be representative of most ancient Greek music. “However, we can recognize that Euripides adopted another principle,” setting words to falling and rising cadences according to their emotional import. As D’Angour puts it, “this was ancient Greek soundtrack music,” and it was apparently so well-received that historian Plutarch tells a story about “thousands of Athenian soldiers held prisoner” in Syracuse: “those few who were able to sing Euripides’ latest songs were able to earn some food and drink.”

As for “the greatest of ancient poet-singers,” Homer, it seems according to reconstructions by the late Professor Martin West of Oxford that Homeric tunes were “fairly monotonous,” explaining perhaps why “the tradition of Homeric recitation without melody emerged from what was originally a sung composition.”

Related Content:

Listen to the Oldest Song in the World: A Sumerian Hymn Written 3,400 Years Ago

Hear the World’s Oldest Instrument, the “Neanderthal Flute,” Dating Back Over 43,000 Years

Free Courses in Ancient History, Literature & Philosophy

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness