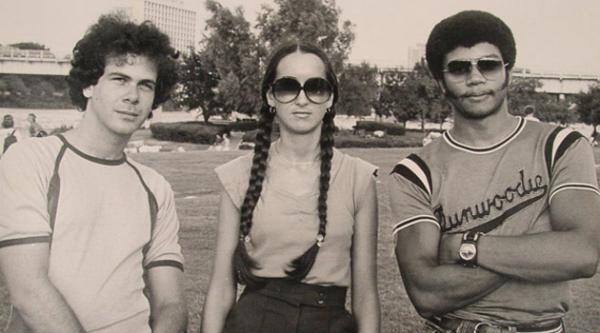

Last year, we revisited the high school days of Neil deGrasse Tyson. Growing up in New York City during the 1970s, Tyson attended Bronx Science (class of ’76), ran an impressive 4:25 mile, captained the school’s wrestling team, and, he fondly recalls, wore basketball sneakers belonging to the Knick’s Walt “Clyde” Frazier. Tyson was, of course, also a precocious student. Famously, Carl Sagan recruited Tyson to study with him at Cornell. But Tyson politely declined and went to Harvard for his undergraduate studies. Then, he headed off to Texas, to start his PhD at UT-Austin. That’s where the photo, taken circa 1980, captures him above — hanging out with friends, and looking hipper than your average astrophysics student.

This photo (now making the rounds on Reddit) originally appeared in a 2012 article published in the Alcalde, the alumni magazine of The University of Texas. To the magazine’s credit, the article takes an unvarnished look at Tyson’s “failed experiment” in Texas. The piece starts with the lede “Neil deGrasse Tyson, MA ’83, is the public face of science. But he says his success has nothing to do with UT.” And, from there, it recounts how professors and university police immediately stereotyped him.

The first comment directed to me in the first minute of the first day by a faculty member I had just met was, ‘You must join the department basketball team!

or

I was stopped and questioned seven times by University police on my way into the physics building. Seven times. Zero times was I stopped going into the gym—and I went to the gym a lot. That says all you need to know about how welcome I felt at Texas.

But the real problem wasn’t race. According to Tyson, “there was simply no room for me to be the full person that I was.” “An obsessive focus on one thing at a time; a strong connection to pop culture, from the moonwalk to the Rubik’s cube; and a refusal to put research first: these traits contributed to Tyson’s failure at UT,” concludes the Alcalde. They also allowed him to flourish later in life.

After his “advisors dissolved his dissertation committee—essentially flunking him,” Tyson transferred to Columbia, earned his PhD in 1988, and became the greatest popularizer of science since Carl Sagan. We like stories with happy endings.

Read more about Tyson’s experience in Texas at the Alcalde.

Related Content:

Neil deGrasse Tyson, High School Wrestling Team Captain, Invented a Physics-Based Wrestling Move

Carl Sagan Writes a Letter to 17-Year-Old Neil deGrasse Tyson (1975)

Neil deGrasse Tyson Lists 8 (Free) Books Every Intelligent Person Should Read