Just yesterday we were musing on perusing rock stars’ bookshelves, and today we learn it has become a reality, if you live in London. Polymath and all-around swell person David Byrne opened the 22nd annual Meltdown Festival this last Monday, and in the spirit of London’s Poetry Library (which is hosting this part of the event), the former Talking Heads frontman has shipped over 250 books to stock his own lending library for the duration of the festival, until August 30.

In his Guardian essay explaining his decision to let you rifle through his collection of music books—some of which were used as research for his own How Music Works—Byrne waxes about the library he loved in his teenage years in suburban Baltimore:

We were desperate to know what was going on in the cool places, and, given some suggestions and direction, the library was one place where that wider exciting world became available. In my little town, the library also had vinyl that one could check out and I discovered avant-garde composers such as Xenakis and Messiaen, folk music from various parts of the world and even some pop records that weren’t getting much radio play in Baltimore. It was truly a formative place.

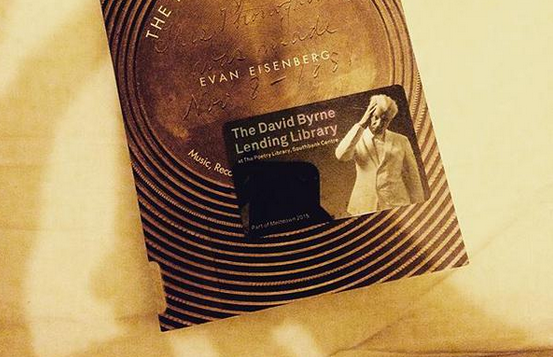

A full list of the books has yet to surface, but a few people are tweeting photos of titles, like Evan Eisenberg’s The Recording Angel: Music, Records and Culture from Aristotle to Zappa or Steve Goodman’s Sonic Warfare: Sound, Affect, and the Ecology of Fear. Squinting our eyes at the promotional photo of Byrne sitting in front of the shelves, we can spot Lester Bangs’ Psychotic Reactions and Carburator Dung, Eric Weisbard’s Listen Again: A Momentary History of Pop Music, Paula Court’s photobook New York Noise: Art and Music from the New York Underground 1978–88; and Thurston Moore’s Mix Tape: The Art of Cassette Culture. (Recognize some other titles? Please add them in the comments.)

Byrne has set up a free-to-borrow system with a credit card on file just in case you abscond with the book, although he does admit it may happen and “so be it.” There’s also an added thrill:

Some of my books may have highlighted bits or notes scrawled in the margins. I hope nothing embarrassing.

Byrne’s programming for the Meltdown Festival can be seen here. Highlights include an a cappella workshop by Petra Haden, a showing of There Will Be Blood with live score by Jonny Greenwood and the London Contemporary Orchestra, the reappearance of Young Marble Giants, Young Jean Lee’s band Future Wife performing We’re Gonna Die with David Byrne as special guest; and many other selections of “Things David Thinks You Should Hear.”

In the meantime, here’s a photo from the fest’s opening of Mr. Byrne riding a portable espresso shop on wheels.

Related Content:

Patti Smith’s List of Favorite Books: From Rimbaud to Susan Sontag

David Byrne: How Architecture Helped Music Evolve

Ted Mills is a freelance writer on the arts who currently hosts the FunkZone Podcast. You can also follow him on Twitter at @tedmills, read his other arts writing at tedmills.com and/or watch his films here.