On Monday, we brought you evidence that Stanley Kubrick invented the tablet computer in 1968’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. Today, we go back forty years further into cinematic history to ask whether Fritz Lang invented the video phone in 1927’s Metropolis. In the clip above, you can watch a scene set in the home of Joh Fredersen, stern master of the vast, futuristic, titular industrial city of 2026. In order to best rule all he surveys — and to complete the image of a 20th-century dystopia — he lives high above the infernal roil of Metropolis, safely ensconced in one of its vertiginous towers and equipped with the latest hulking, wall-mounted, inexplicably paper-spouting video phone technology.

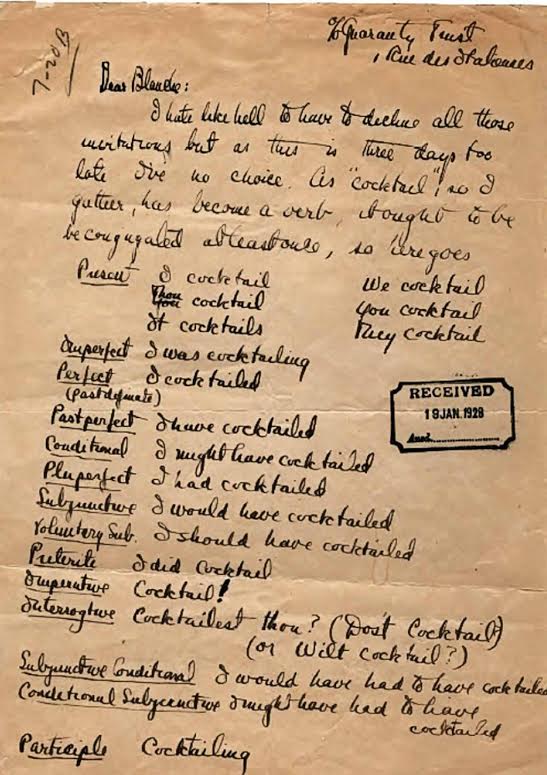

Fredersen, writes Joe Malia in his notes on video phones in film, “appears to use four separate dials to arrive at the correct frequency for the call. Two assign the correct call location and two smaller ones provide fine video tuning. He then picks up a phone receiver with one hand and uses the other to tap a rhythm on a panel that is relayed to the other phone and displayed as flashes of light to attract attention.”

Not content to infer the mechanics of these imaginary devices, Malia would go on to create the supercut below, a survey of video phones throughout the history of film and television, from Metropolis onward, including a stop at 2001:

The supercut also includes a clip from Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner, whose (on the whole, astonishingly timeless) design I called out for using video phones in a video essay of my own. In reality, contrary to all these 20th-century visions of the far-flung future, video phone technology didn’t develop quite as rapidly as predicted, and when it did develop, it didn’t spread in quite the same way as predicted. Even the rich world of 2015 lacks bulky video phone boxes in every home and on every street corner, but with voice over internet protocol services like Skype, many in even the poorest parts of the world can effectively make better video phone calls than these grand-scale sci-fi productions dared imagine — then again, they do often make them on tablets more or less straight out of 2001.

Related Content:

Did Stanley Kubrick Invent the iPad in 2001: A Space Odyssey?

A 1947 French Film Accurately Predicted Our 21st-Century Addiction to Smartphones

Nikola Tesla Accurately Predicted the Rise of the Internet & Smart Phone in 1926

Colin Marshall writes on cities, language, Asia, and men’s style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.