When I was a kid, I spent a lot of time at the Indianapolis Star, where my mother worked in what was then referred to as the “women’s pages.” She kept me busy returning the photos that accompanied marriage and engagement announcements, using the SASEs the young brides had supplied. After that, I’d hit the printing floor, where veteran workers sported square caps folded from the previous day’s edition, as that day’s issue clacked on tracks overhead. If I was lucky, someone would make me a gift of my name, set in hot type.

The Star still publishes — I shudder to report that its website seems to have renamed it IndyStar… — but cultural and digital advances have relegated all of the particulars mentioned above to the scrap pile.

They came rushing back with wild, Proustian urgency when Osamu Yamamoto, a master printer at Benrido Collotype Atelier in Kyoto, mentions the smell of the ink, in the short documentary above, how over the years, it has seeped into his skin, and become a part of his being.

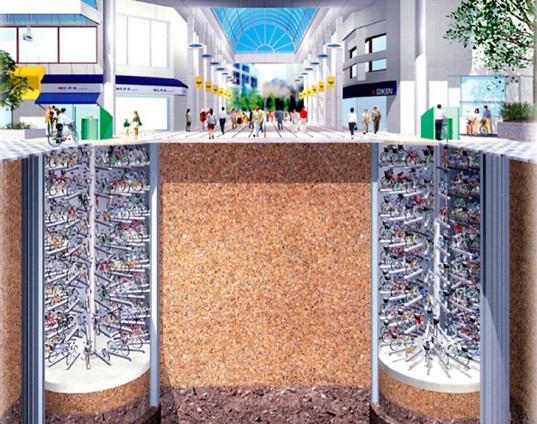

Collotype, defined by the Getty Conservation Institute as “a screenless photomechanical process that allows high-quality prints from continuous-tone photographic negatives,” has been on the way out since the 70s. As master printer Yamamoto notes, it’s a low-efficiency, small batch operation, involving messy matrixes, hand-operated presses, and heavy iron machines that give off a sort of animal warmth when working.

Rather than pressmen’s caps, Benrido’s shirtless printers wear hachimaki, rubber aprons, and purple disposable gloves.

Filmmaker Fritz Schumann (whose film on the oldest hotel in Japan we previously featured before) evokes the workplace — one of two remaining collotype companies in the world — through small details like the plastic-wrapped digital Hamtaro clock and also by drawing viewers’ attention to the number of years logged by each employee. The art of collotype takes a long time to master and novices appear to be in short supply.

Should we conceive of this operation as a quaint relic, creeping along thanks to the whimsy of a few nostalgia buffs?

Surprisingly, no. The laborious collotype process remains the best way to duplicate precious artworks and historic documents. The way the ink interacts with reticulations in the gelatin surface atop results in subtleties that pixellated digital images cannot hope to achieve.

Visitors to the studio may support the enterprise by picking up a handful of collotype-printed postcards in the gift shop, but the office of the Japanese Emperor is the one who’s really keeping them in business, with orders to copy hundreds of delicate, centuries old scrolls, paintings and letters.

Like a circle in a circle…cultural preservation via cultural preservation! Perhaps the smell of the ink will prevail.

Related Content:

Hōshi: A Short Film on the 1300-Year-Old Hotel Run by the Same Family for 46 Generations

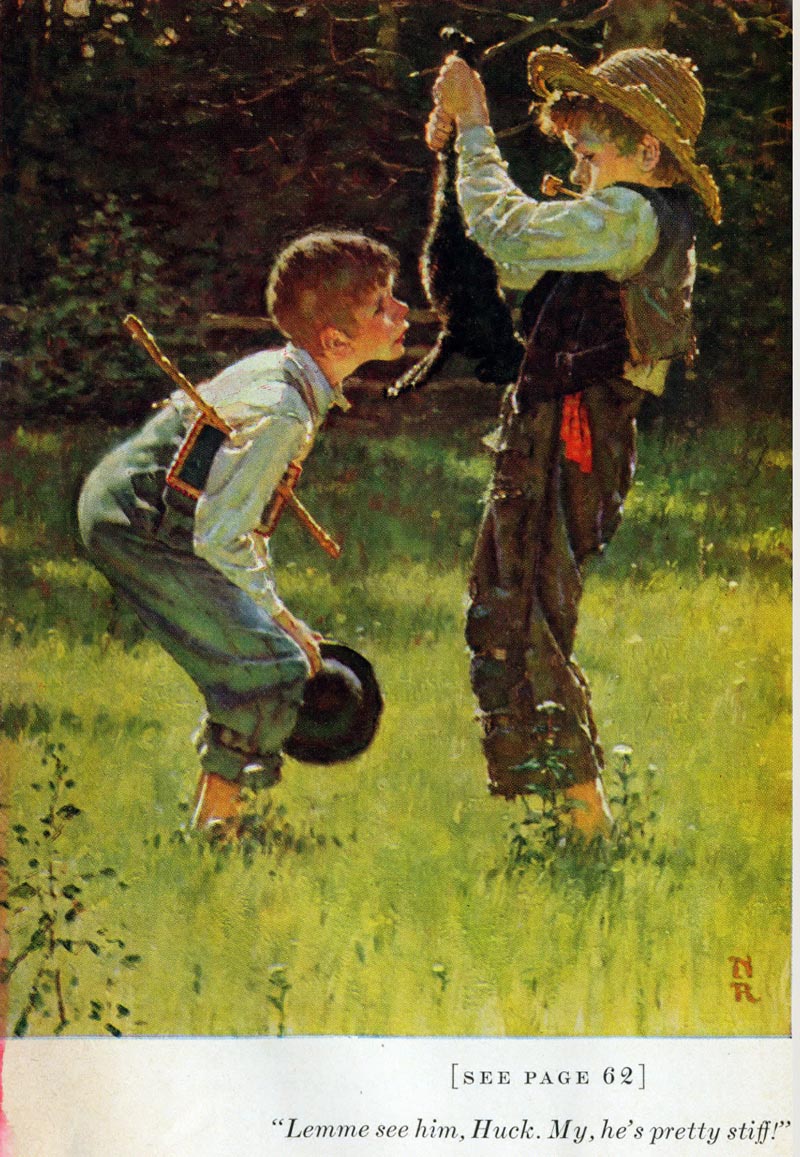

Mark Twain Wrote the First Book Ever Written With a Typewriter

- Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Follow her @AyunHalliday