Dig that heavy metal / Underneath your hood / Baby I can work all night / Believe I got the perfect tools / Talkin’ bout love

Last February, Led Zeppelin released a deluxe, re-mastered version of their sprawling 1975 double album Physical Graffiti, a record perhaps best known for the epic, orchestral grandeur of the 8 1/2 minute “Kashmir” (not to be outdone by the 11-minute “In My Time of Dying”). In an album full of stylistic departures and solid returns to form, one track, “Trampled Under Foot,” manages to be both, driven by down-and-dirty blues and uptown 70s funk, courtesy of John Paul Jones’ Stevie Wonder-inspired organ groove. With lyrics Robert Plant himself described as “raunchy,” the song—one of Plant’s favorites—may be the band’s most 70s-sounding. That’s not to say it’s dated, only that it most perfectly captures the sound of the American street represented on the album cover, a shot of two adjacent tenements on New York City’s St. Mark’s Place.

Now, listeners can enter those buildings and tool around the apartments, courtesy of the interactive video at the top of the post (view it in a larger format here), which features a previously unreleased rough mix of the track called “Brandy & Coke.” Conceived and directed by Hal Kirkland, the video pulls together some of my favorite things—the period design and styling of That ‘70s Show, the most inventive tricks of the music video age, a la Tom Petty or Peter Gabriel, and of course, Zep—with the added 21st century technology of online interactivity. Click the arrow keys while the video plays and you’re transported from one vivid tableaux to another, some representing funky apartment scenes, others something else entirely. The video also integrates footage from Zeppelin’s performance of the song at Earl’s Court in ’75.

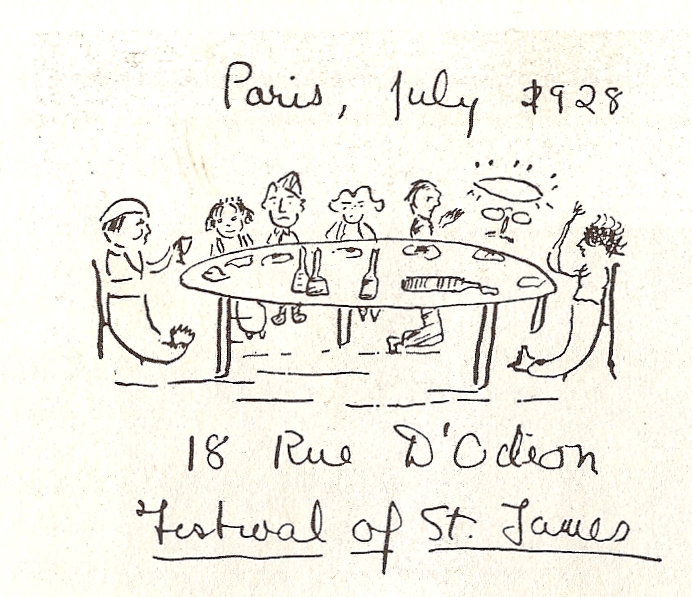

Clever references abound, like the nod to godfather of fantasy cinema Georges Méliès (above) and an allusion to the classic MTV moon landing intro (below). Overall, it’s an astonishing visual feast that hearkens back to the very best in music video technology, a seemingly lost art that Kirkland and company may singlehandedly resurrect. See Kirkland’s site for more of his internet age music video creations, including “Sour—Hibi No Neiro,” shot entirely on webcams.

Related Content:

Led Zeppelin Plays One of Its Earliest Concerts (Danish TV, 1969)

Hear Led Zeppelin’s Mind-Blowing First Recorded Concert Ever (1968)

Jimmy Page Describes the Creation of Led Zeppelin’s “Whole Lotta Love”

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness