The good folks at Blank on Blank have been breathing new life into long-lost recorded interviews with cultural icons by turning them into animated shorts. In the past, they have made films featuring the likes of Janis Joplin, David Foster Wallace, Jim Morrison and Dave Brubeck. For their most recent release, they do Ray Bradbury, the beloved sci-fi author and monorail enthusiast. You can watch it above.

In 2012, Lisa Potts found a cassette tape wedged behind a dresser. It contained an interview she did with Bradbury back in 1972 when she was a student journalist. Potts and fellow student Chadd Coates talked to the author in the back of a car while they were making their way from Bradbury’s West L.A. home to Chapman College in Orange County where he was slated to give a lecture.

In the interview, Bradbury expounds on a wide range of topics – from the importance of friends – “That’s what friends are, the people who share your crazy outlook and protect you from the world” – to his fear of driving – “The whole activity is stupid.”

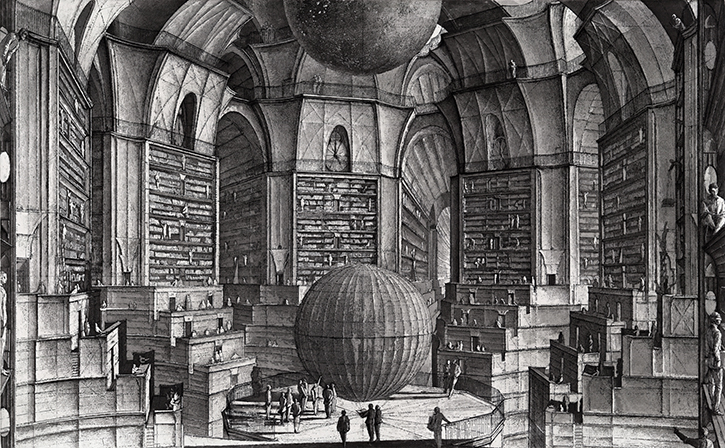

But the area where he seems to get the most passionate is, not surprisingly, about the act of creating. According to Bradbury, you don’t need a fancy, overpriced MFA to write. He never went to college after all. His school was his local public library. What you really need to be a writer is an obsessive love of writing, friends who are willing to nourish your obsession and a willingness to be a little crazy.

I am a dedicated madman, and that becomes its own training. If you can’t resist, if the typewriter is like candy to you, you train yourself for a lifetime. Every single day of your life, some wild new thing to be done. You write to please yourself. You write for the joy of writing. Then your public reads you and it begins to gather around your selling a potato peeler in an alley, you know. The enthusiasm, the joy itself draws me. So that means every day of my life I’ve written. When the joy stops, I’ll stop writing.

For anyone sweating blood in a coffee shop over a stubborn screenplay or novel, lines like that are balm for the soul. The whole interview has this same infectious joy of creating. Bradbury, by the way, wrote up until he died at the age of 91.

Related Content:

Ray Bradbury Gives 12 Pieces of Writing Advice to Young Authors (2001)

A Day in the Afterlife: Revisiting the Life & Times of Philip K. Dick

Animations Revive Lost Interviews with David Foster Wallace, Jim Morrison & Dave Brubeck

Jonathan Crow is a Los Angeles-based writer and filmmaker whose work has appeared in Yahoo!, The Hollywood Reporter, and other publications. You can follow him at @jonccrow. And check out his blog Veeptopus, featuring lots of pictures of badgers and even more pictures of vice presidents with octopuses on their heads. The Veeptopus store is here.