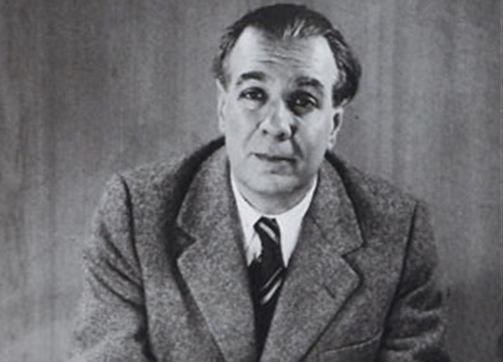

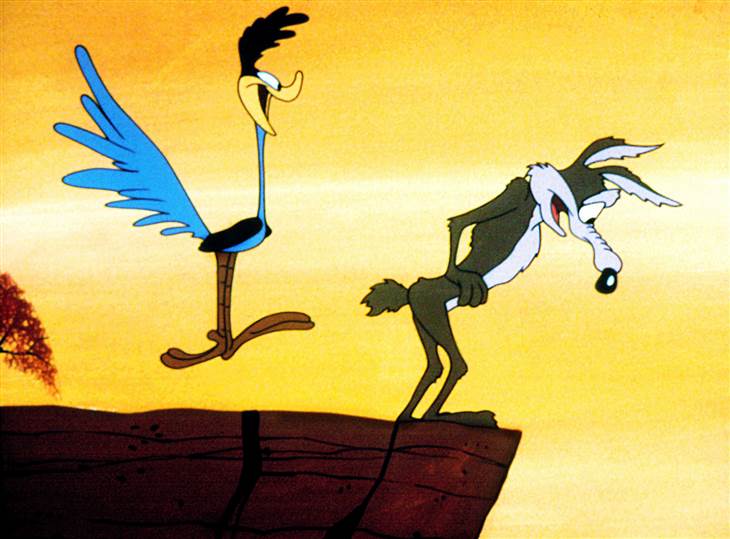

“Jorge Luis Borges 1951, by Grete Stern” by Grete Stern (1904–1999). Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Jorge Luis Borges’ terse, mind-expanding stories reshaped modern fiction. He was one of the first authors to mix high culture with low, merging such popular genres as science fiction and the detective story with heady philosophical discourses on authorship, reality and existence. His story “The Garden of the Forking Paths,” which describes a novel that is also a labyrinth, presaged the hypertextuality of the internet age. His tone of ironic detachment influenced generations of Latin American authors. The BBC argued that Borges was the most important writer of the 20th century.

Of course, Borges wasn’t just an author. When not writing fiction, Borges worked as a literary critic, occasional film critic, a librarian, and, for a spell, as the director of the Biblioteca Nacional in Buenos Aires. His tastes were famously eclectic. He did not think of much of canonical writers like Goethe, Jane Austen, James Joyce and Gabriel Garcia Marquez. He favored the 19th storytellers like Edgar Allan Poe and Rudyard Kipling.

In 1985, Argentine publisher Hyspamerica asked Borges to create A Personal Library — which involved curating 100 great works of literature and writing introductions for each volume. Though he only got through 74 books before he died of liver cancer in 1988, Borges’s selections are fascinating and deeply idiosyncratic. He listed adventure tales by Robert Louis Stevenson and H.G. Wells alongside exotic holy books, 8th century Japanese poetry and the musing of Kierkegaard. You can see the full list below. A number of the selected works can be found in our Free eBooks and Free Audio Books collections.

1. Stories by Julio Cortázar (not sure if this refers to Hopscotch, Blow-Up and Other Stories, or neither)

2. & 3. The Apocryphal Gospels

4. Amerika and The Complete Stories by Franz Kafka

5. The Blue Cross: A Father Brown Mystery by G.K. Chesterton

6. & 7. The Moonstone by Wilkie Collins

8. The Intelligence of Flowers by Maurice Maeterlinck

9. The Desert of the Tartars by Dino Buzzati

10. Peer Gynt and Hedda Gabler by Henrik Ibsen

11. The Mandarin: And Other Stories by Eça de Queirós

12. The Jesuit Empire by Leopoldo Lugones

13. The Counterfeiters by André Gide

14. The Time Machine and The Invisible Man by H.G. Wells

15. The Greek Myths by Robert Graves

16. & 17. Demons by Fyodor Dostoyevsky

18. Mathematics and the Imagination by Edward Kasner

19. The Great God Brown and Other Plays, Strange Interlude, and Mourning Becomes Electra by Eugene O’Neill

20. Tales of Ise by Ariwara no Narihara

21. Benito Cereno, Billy Budd, and Bartleby, the Scrivener by Herman Melville

22. The Tragic Everyday, The Blind Pilot, and Words and Blood by Giovanni Papini

23. The Three Impostors

24. Songs of Songs tr. by Fray Luis de León

25. An Explanation of the Book of Job tr. by Fray Luis de León

26. The End of the Tether and Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad

27. The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire by Edward Gibbon

28. Essays & Dialogues by Oscar Wilde

29. Barbarian in Asia by Henri Michaux

30. The Glass Bead Game by Hermann Hesse

31. Buried Alive by Arnold Bennett

32. On the Nature of Animals by Claudius Elianus

33. The Theory of the Leisure Class by Thorstein Veblen

34. The Temptation of St. Antony by Gustave Flaubert

35. Travels by Marco Polo

36. Imaginary lives by Marcel Schwob

37. Caesar and Cleopatra, Major Barbara, and Candide by George Bernard Shaw

38. Macus Brutus and The Hour of All by Francisco de Quevedo

39. The Red Redmaynes by Eden Phillpotts

40. Fear and Trembling by Søren Kierkegaard

41. The Golem by Gustav Meyrink

42. The Lesson of the Master, The Figure in the Carpet, and The Private Life by Henry James

43. & 44. The Nine Books of the History of Herodotus by Herdotus

45. Pedro Páramo by Juan Rulfo

46. Tales by Rudyard Kipling

47. Vathek by William Beckford

48. Moll Flanders by Daniel Defoe

49. The Professional Secret & Other Texts by Jean Cocteau

50. The Last Days of Emmanuel Kant and Other Stories by Thomas de Quincey

51. Prologue to the Work of Silverio Lanza by Ramon Gomez de la Serna

52. The Thousand and One Nights

53. New Arabian Nights and Markheim by Robert Louis Stevenson

54. Salvation of the Jews, The Blood of the Poor, and In the Darkness by Léon Bloy

55. The Bhagavad Gita and The Epic of Gilgamesh

56. Fantastic Stories by Juan José Arreola

57. Lady into Fox, A Man in the Zoo, and The Sailor’s Return by David Garnett

58. Gulliver’s Travels by Jonathan Swift

59. Literary Criticism by Paul Groussac

60. The Idols by Manuel Mujica Láinez

61. The Book of Good Love by Juan Ruiz

62. Complete Poetry by William Blake

63. Above the Dark Circus by Hugh Walpole

64. Poetical Works by Ezequiel Martinez Estrada

65. Tales by Edgar Allan Poe

66. The Aeneid by Virgil

67. Stories by Voltaire

68. An Experiment with Time by J.W. Dunne

69. An Essay on Orlando Furioso by Atilio Momigliano

70. & 71. The Varieties of Religious Experience and The Study of Human Nature by William James

72. Egil’s Saga by Snorri Sturluson

73. The Book of the Dead

74. & 75. The Problem of Time by J. Alexander Gunn

As you will observe, Borges’ list is very short on books by women writers. As a counter-offering, you might want to explore this list: 74 Essential Books for Your Personal Library: A List Curated by Female Creatives.

Related Content:

Jorge Luis Borges’ 1967–8 Norton Lectures On Poetry (And Everything Else Literary)

Jorge Luis Borges’ Favorite Short Stories (Read 7 Free Online)

Jonathan Crow is a Los Angeles-based writer and filmmaker whose work has appeared in Yahoo!, The Hollywood Reporter, and other publications. You can follow him at @jonccrow. And check out his blog Veeptopus, featuring lots of pictures of badgers and even more pictures of vice presidents with octopuses on their heads. The Veeptopus store is here.