Matt Zoller Seitz is easily one of the finest film critics working today. Over the years, he has done quite a lot of work unpacking the dense visual world of filmmaker Wes Anderson, culminating in a gorgeous coffee table book called, aptly, The Wes Anderson Collection. Today you can explore a series of video essays that delve into the filmmaker’s work. Zoller Seitz argues that Anderson’s distinctive look is not merely empty aesthetics. Instead, he asserts that there is substance to Anderson’s style.

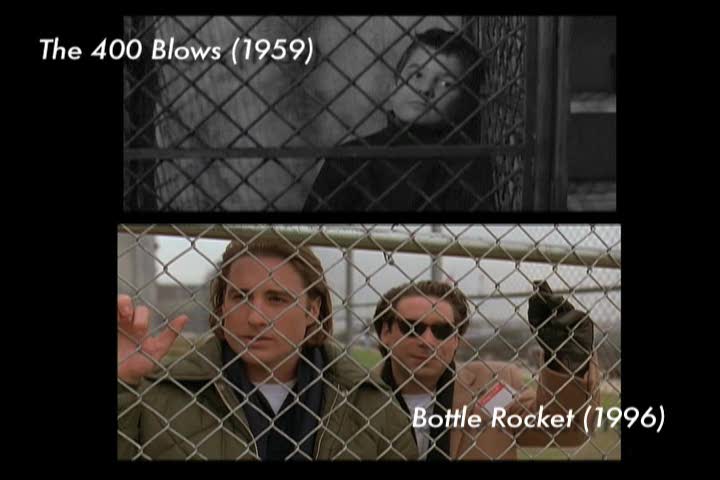

The first video outlines three of Anderson’s biggest cinematic influences. The filmmaker’s love of virtuous camera moves and preoccupation with fallen geniuses can be traced right back to Orson Welles. His focus on young people struggling to find peace in the adult world is influenced by Francois Truffaut, particularly his masterpiece 400 Blows. And the third, and perhaps most surprising, influence is Charles Schulz’s comic strip Peanuts.

In this second video, Zoller Seitz notes the stylistic similarities between Anderson and directors Mike Nichols, Richard Lester, and Martin Scorsese. It’s not terribly hard to see traces of The Graduate or Hard Day’s Night in Anderson’s movies, but Goodfellas? Zoller Seitz makes a pretty convincing argument.

While the previous videos come close to hagiography, the third video compares Anderson with another obvious influence Hal Ashby. It’s just about impossible to imagine Anderson’s delightfully twee world and deadpan humor without Ashby’s Harold and Maude. Like Anderson, Ashby too slipped effortlessly between different tones and different genres. But Anderson’s movies focus exclusively on upper class white people, something that he has been frequently criticized for. Ashby’s movies, on the other hand, cast a much wider socio-economic net. After watching this video, you get the sense that Ashby might be the better filmmaker.

The fourth video lays out how Anderson’s tendency of defining characters through their wardrobe goes right back to writer J.D. Salinger.

And with the fifth and final video, Zoller Seitz pulls together all of his arguments by annotating the prologue to arguably Anderson’s best and most influential movie, The Royal Tenenbaums.

Related Content:

The Perfect Symmetry of Wes Anderson’s Movies

A Glimpse Into How Wes Anderson Creatively Remixes/Recycles Scenes in His Different Films

Watch Wes Anderson’s Charming New Short Film, Castello Cavalcanti, Starring Jason Schwartzman

Wes Anderson’s First Short Film: The Black-and-White, Jazz-Scored Bottle Rocket (1992)

Watch 7 New Video Essays on Wes Anderson’s Films: Rushmore, The Royal Tenenbaums & More

Jonathan Crow is a Los Angeles-based writer and filmmaker whose work has appeared in Yahoo!, The Hollywood Reporter, and other publications. You can follow him at @jonccrow. And check out his blog Veeptopus, featuring lots of pictures of badgers and even more pictures of vice presidents with octopuses on their heads. The Veeptopus store is here.