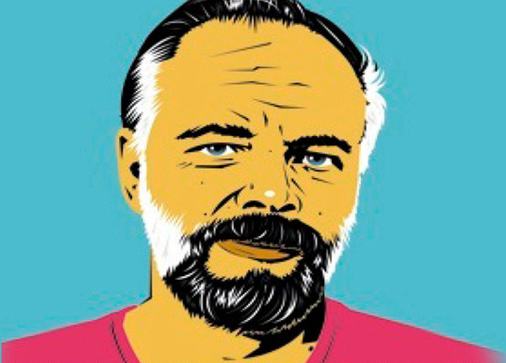

For Sigmund Freud, a joke was never just a joke, but a window into the unconscious, laughter an anxious symptom of recognition that something lost has resurfaced, distorted into humor. For Slovenian psychoanalytic philosopher Slavoj Žižek, jokes function similarly. And yet, in keeping with his commitment to leftist politics, he uses jokes not to expose the hidden terrain of individual psyches but “to evoke binds of historical circumstances hard to indicate by other means.” So writes Kenneth Baker in a brief SFGate review of the recent Žižek’s Jokes, a book-length compilation of Žižekisms published by MIT Press. Baker also points out a defining feature of Žižek’s humor: “Many of Žižek’s jokes preserve or even amplify the vulgarity of their demotic or pop cultural origins.” Take the NSFW joke he tells above at the expense of a Montenegrin friend. Žižek explains the joke as part of his maybe dubious strategy of countering racism with “progressive racism” or the “solidarity” of “shared obscenity”—the use of potentially uncomfortable ethnic humor to expose uncomfortable political truths that get repressed or papered over by politeness.

Some of Žižek’s humor is more trigger-warning worthy, such as his retelling of this old Soviet dissident joke or this “very dirty joke” he reportedly heard from a Palestinian Christian acquaintance. On the other hand, some of his “dirty jokes” replace vulgarity with theory. For example, Žižek likes to tell a “truly obscene” version of the famously filthy joke “The Aristocrats,” which you’ll know if you’ve seen, or only read about, the film of the same name. And yet in his take, instead of a series of increasingly disgusting acts, the family performs “a short course in Hegelian thought, debating the true meaning of the negativity, of sublation, of absolute knowing, etc.” This is perhaps an example of what Baker refers to as Žižekian jokes that are “baffling to readers not conversant with the gnarly dialectics of his thought, which does not lend itself easily to sampling.” Be that as it may, much of Žižek’s humor works without the theoretical context, and some of it is even tame enough for water cooler interludes. Below are four examples of “safe” jokes, culled from website Critical Theory’s list of “The 10 Best Žižek Jokes to Get You Through Finals” (which itself culls from Žižek’s Jokes). “Some of the jokes [in Žižek’s book] provide hilarious insights into Hegelian dialectics, Lacanian psychoanalysis or ideology,” writes Critical Theory, “Others are just funny, and most are somewhat offensive—a characteristic Žižek admittedly doesn’t care to correct.”

#1 There is an old Jewish joke, loved by Derrida…

about a group of Jews in a synagogue publicly admitting their nullity in the eyes of God. First, a rabbi stands up and says: “O God, I know I am worthless. I am nothing!” After he has finished, a rich businessman stands up and says, beating himself on the chest: “O God, I am also worthless, obsessed with material wealth. I am nothing!” After this spectacle, a poor ordinary Jew also stands up and also proclaims: “O God, I am nothing.” The rich businessman kicks the rabbi and whispers in his ear with scorn: “What insolence! Who is that guy who dares to claim that he is nothing too!”

#4 When the Turkish Communist writer Panait Istrati visited the Soviet Union in the mid- 1930s, the time of the big purges…

and show trials, a Soviet apologist trying to convince him about the need for violence against the enemies evoked the proverb “You can’t make an omelet without breaking eggs,” to which Istrati tersely replied: “All right. I can see the broken eggs. Where’s this omelet of yours?”

We should say the same about the austerity measures imposed by IMF: the Greeks would have the full right to say, “OK, we are breaking our eggs for all of Europe, but where’s the omelet you are promising us?”

#7 This also makes meaningless the Christian joke…

according to which, when, in John 8:1–11, Christ says to those who want to stone the woman taken in adultery, “Let him who is without sin among you be the first to throw a stone!” he is immediately hit by a stone, and then shouts back: “Mother! I asked you to stay at home!”

#8 In an old joke from the defunct German Democratic Republic,…

a German worker gets a job in Siberia; aware of how all mail will be read by censors, he tells his friends: “Let’s establish a code: if a letter you will get from me is written in ordinary blue ink, it is true; if it is written in red ink, it is false.” After a month, his friends get the first letter, written in blue ink: “Everything is wonderful here: stores are full, food is abundant, apartments are large and properly heated, movie theaters show films from the West, there are many beautiful girls ready for an affair—the only thing unavailable is red ink.”

And is this not our situation till now? We have all the freedoms one wants—the only thing missing is the “red ink”: we “feel free” because we lack the very language to articulate our unfreedom. What this lack of red ink means is that, today, all the main terms we use to designate the present conflict —“war on terror,” “democracy and freedom,” “human rights,” etc.—are false terms, mystifying our perception of the situation instead of allowing us to think it. The task today is to give the protesters red ink.

For more of Slavoj Žižek’s witticism, vulgarity, and humorous critiques of ideological formations, political history, and Hegelian and Lacanian thought, pick up a copy of Žižek’s Jokes, and see this Youtube compilation of the politically incorrect leftist philosopher’s humor caught on tape.

via Critical Theory

Related Content:

Slavoj Žižek: What Fullfils You Creatively Isn’t What Makes You Happy

Žižek!: 2005 Documentary Reveals the “Academic Rock Star” and “Monster” of a Man

In His Latest Film, Slavoj Žižek Claims “The Only Way to Be an Atheist is Through Christianity”

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness.