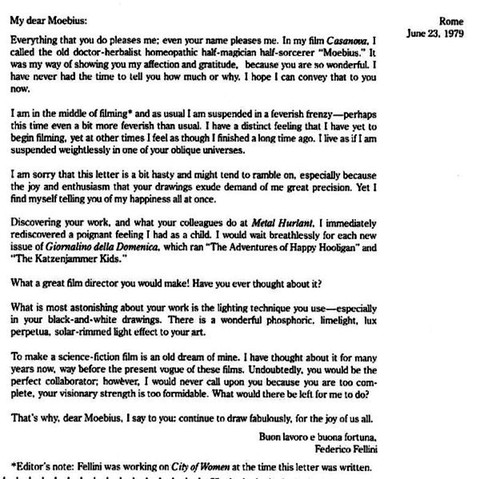

If you believe that artistic collaborations occur in the afterlife, few could sound more intriguing than one between the creators pictured, in life, above: Federico Fellini, born 94 years ago today and gone for the past twenty, and Jean Giraud, who passed in 2012. The Italian director Fellini, we need hardly explain, made such hauntingly flamboyant films as La Dolce Vita, 8½, and Satyricon. The Franco-Belgian comic artist Giraud, better known as Mœbius, took his form to its highest aesthetic level with works like Arzach, The Airtight Garage of Jerry Cornelius, The Incal, and, under his alternate pseudonym Gir, the unconventional Wild-West series Blueberry. (You can learn more by watching the documentary In Search of Mœbius, previously featured here.) Reflect, for a moment, on what bizarre, fantastical, yet psychologically concrete visions these two imaginations could together realize.

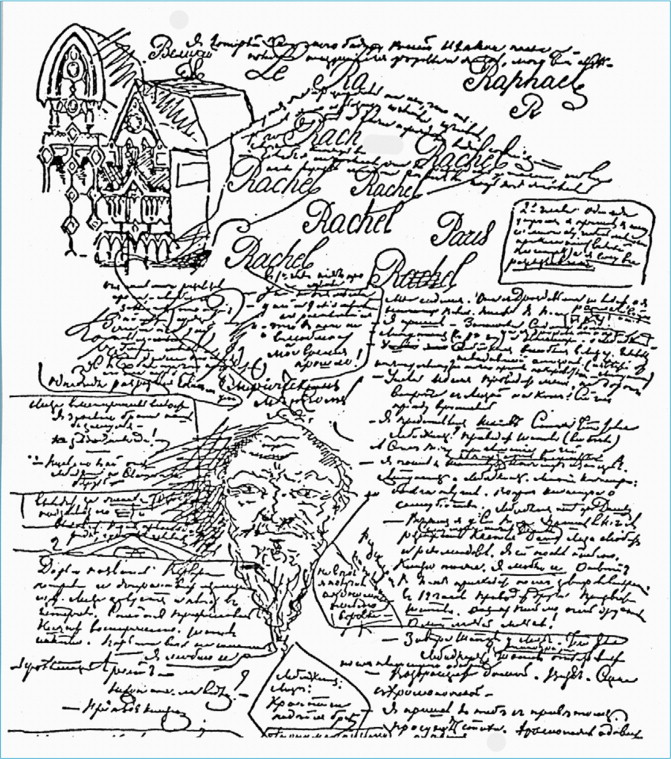

Fellini quite admired Giraud, considering him at the level of Picasso and Matisse. On Italian television, he once called him “a unique talent endowed with an extraordinary visionary imagination that’s constantly renewed and never vulgar” who “disturbs and consoles” and possesses “the ability to transport us into unknown worlds where we encounter unsettling characters.” The 1979 letter above, which Fellini wrote while shooting City of Women, continues this line of praise in a direct manner. “Everything you do pleases me,” he says. “Even your name pleases me.” He describes the qualities of Mœbius’ work that continue to win him admirers, from “the joy and enthusiasm your drawings exude” (which “demand of me a great precision”) to “the lighting technique you use” to feeling “suspended weightlessly in one of your oblique universes.” But above all the other lines, one aside in particular gets my own imagination running: “What a great film director you would make! Have you ever thought about it?”

Related Content:

The Inscrutable Imagination of the Late Comic Artist Mœbius

Federico Fellini Introduces Himself to America in Experimental 1969 Documentary

Fellini’s Fantastic TV Commercials

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on cities, Asia, film, literature, and aesthetics. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on his brand new Facebook page.