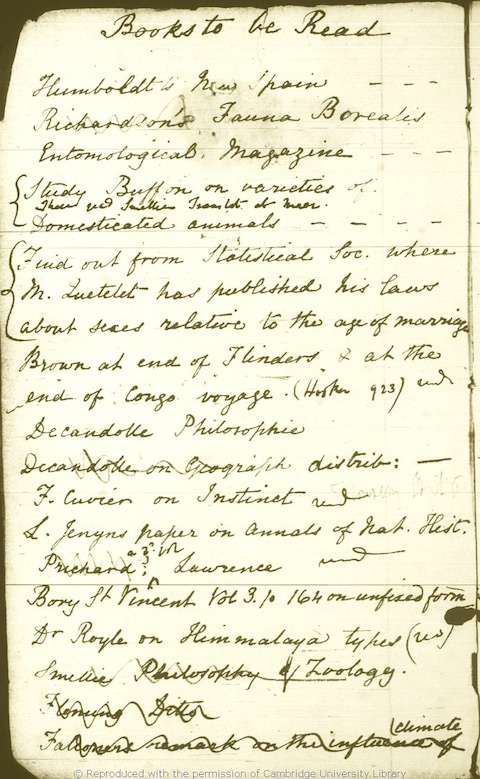

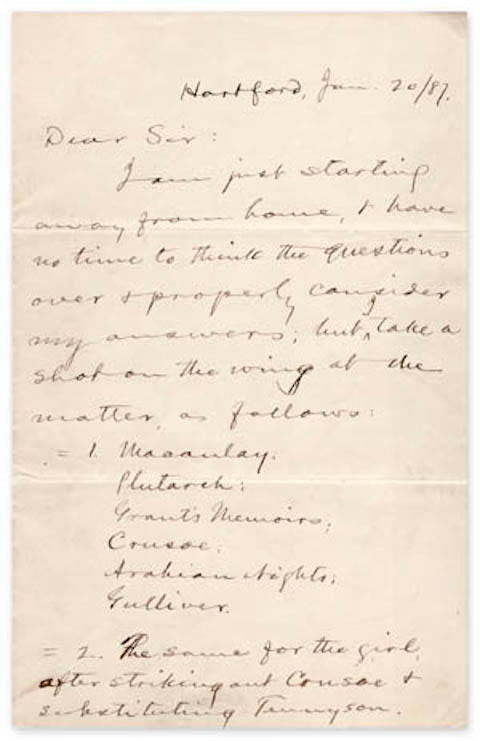

In January of 1887, Mark Twain wrote the above letter to a Reverend Charles D. Crane, pastor of a Methodist Episcopal Church in Maine, to advise him of the most suitable reading for both children and adults. Twain’s letter—which, as he did nearly all his letters, he signed with his given name of Samuel Clemens (or “S.L. Clemens”)—came in response to a query in three parts from the Rev. Crane. But we do not seem to have Crane’s letter (at least a thorough search of the exhaustive catalog at the online Mark Twain Project yields no results.) Nonetheless, we can reasonably infer that he asked the famous author—who was between Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court—something like the following:

1) What books should young boys read? 2) And young girls? … 3) [and both/either] What should grown-ups read? [and/or] What are Mr. Samuel Clemens’ favorite books?

Twain, in a hurry, “took a shot on the wing” and replied with the letter below, which, despite his protestations of haste, seems fairly well-considered. I’ll admit that the ambiguity of the last sentence, however, gives me the researcher’s buzz to go back and dig through more archives for Crane’s original letter.

Dear Sir:

I am just starting away from home, & have no time to think the questions over & properly consider my answers; but I take a shot on the wing at the matter, as follows:

1.Macaulay;

Plutarch;

Grant’s Memoirs;

Crusoe;

Arabian Nights;

Gulliver.

= 2. The same for the girl, after striking out out Crusoe & substituting Tennyson.

I can’t answer No. 3 in this sudden way. When one is going to choose twelve authors, for better for worse, forsaking fathers & mothers to cling unto them & unto them alone, until death shall them part, there is an awfulness about the responsibility that makes marriage with one mere individual & divorcible woman a sacrament sodden with levity by comparison.

In my list I know I should put Shakspeare [sic]; & Browning; & Carlyle (French Revolution only); Sir Thomas Malory (King Arthur); Parkman’s Histories (a hundred of them if there were so many); Arabian Nights; Johnson (Boswell’s), because I like to see that complacent old gasometer listen to himself talk; Jowett’s Plato; & “B.B.” (a book which I wrote some years ago, not for publication but just for my own private reading.)

I should be sure of these; & I could add the other three — but I should want to hold the opportunity open a few years, so as to make no mistake.

Truly Yours

S.L. CLEMENS

See all six manuscript pages of Twain’s letter (and zoom in to examine them closely) at the Shapell Manuscript Foundation. We’ve added links to Twain’s recommended texts above. You can find many in our Free eBooks and Free Audio Books collections.

Related Content:

Christopher Hitchens Creates a Reading List for Eight-Year-Old Girl

Neil deGrasse Tyson Lists 8 (Free) Books Every Intelligent Person Should Read.

“Nothing Good Gets Away”: John Steinbeck Offers Love Advice in a Letter to His Son (1958)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness