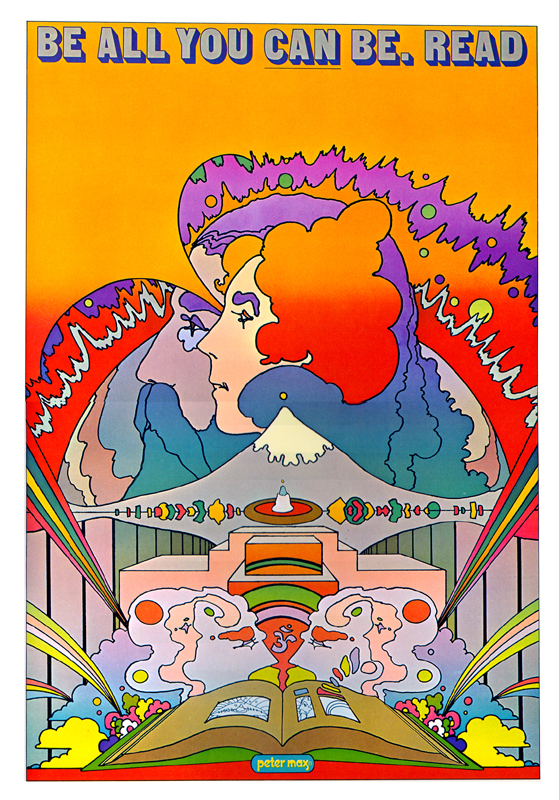

In 1969, Peter Max was creating psychedelic illustrations that captured the countercultural spirit of the 1960s. Bright, trippy, and thought-provoking, Max’s artwork fused together “eastern yogi philosophy, astronomy, comic books, studies in color, and music.” And it certainly found an audience. By the late 60s, college dorm rooms across the U.S. were plastered with Max’s posters. 72 corporations — from General Electric to Burlington Mills, a manufacturer of socks — licensed his art for commercial use. Meanwhile, in ’69, Max appeared on The Tonight Show, The Ed Sullivan Show, and the cover of LIFE magazine (with main article titled “Peter Max: Portrait of the artist as a very rich man”).

Even while the corporate gigs were rolling in, the German-born illustrator took on less commercial projects, like creating this poster for National Library Week, an annual event organized by the American Library Association. Measuring 36 x 24 inches, the 1969 poster, aesthetically speaking, is vintage Max. And it carries a message that sounds as good today as it did then: “Be All You Can Be. Read.” Now dare I steer you toward of our collection of 500 Free eBooks? An easy way to make you, a better you.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. It’s a great way to see our new posts, all bundled in one email, each day.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

via Biblioklept