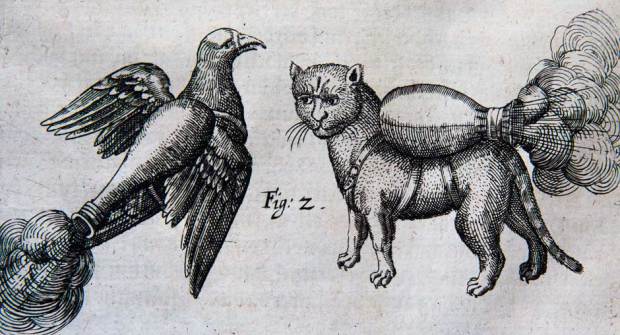

Paw prints and feline urine stains on a medieval scribe’s manuscript, perhaps they weren’t entirely out of the ordinary in the 15th century. But cats strapped to mini-powder kegs, bounding off to burn down a town — now that’s pretty unusual.

The incendiary feline featured above (and elsewhere on this page) comes from a digitized version of an early 16th century military manual written by Franz Helm. An artillery master, Helm wrote about a broad and imaginative set of destructive ideas for siege warfare. Although my German is somewhat rusty, I got the sense that he was awfully fond of exploding sacks, barrels, and various other receptacles, and eventually decided to combine these ideas with an unwitting animal delivery system. These animals, according to Helm’s guide, would allow a commander to “set fire to a castle or city which you can’t get at otherwise.”

The text was originally digitized by the University of Pennsylvania, and a UPenn historian named Mitch Fraas decided to take a closer look at this strange exploding cat business. According to Fraas, the accompanying text reads:

“Create a small sack like a fire-arrow … if you would like to get at a town or castle, seek to obtain a cat from that place. And bind the sack to the back of the cat, ignite it, let it glow well and thereafter let the cat go, so it runs to the nearest castle or town, and out of fear it thinks to hide itself where it ends up in barn hay or straw it will be ignited.”

That’s the military strategy in a nutshell. Seems like a great idea, apart from the fact that cats are notoriously unpredictable. In any case, it’s Friday, so here are more illustrations of weaponized cats to round out your work week.

For more of Helm’s work, head on over to Penn in Hand: Selected Manuscripts.

via National Post

Ilia Blinderman is a Montreal-based culture and science writer. Follow him at @iliablinderman, or read more of his writing at the Huffington Post.

Related Content:

How to Potty Train Your Cat: A Handy Manual by Charles Mingus

Humans Fall for Optical Illusions, But Do Cats?

Thomas Edison’s Boxing Cats (1894), or Where the LOLCats All Began