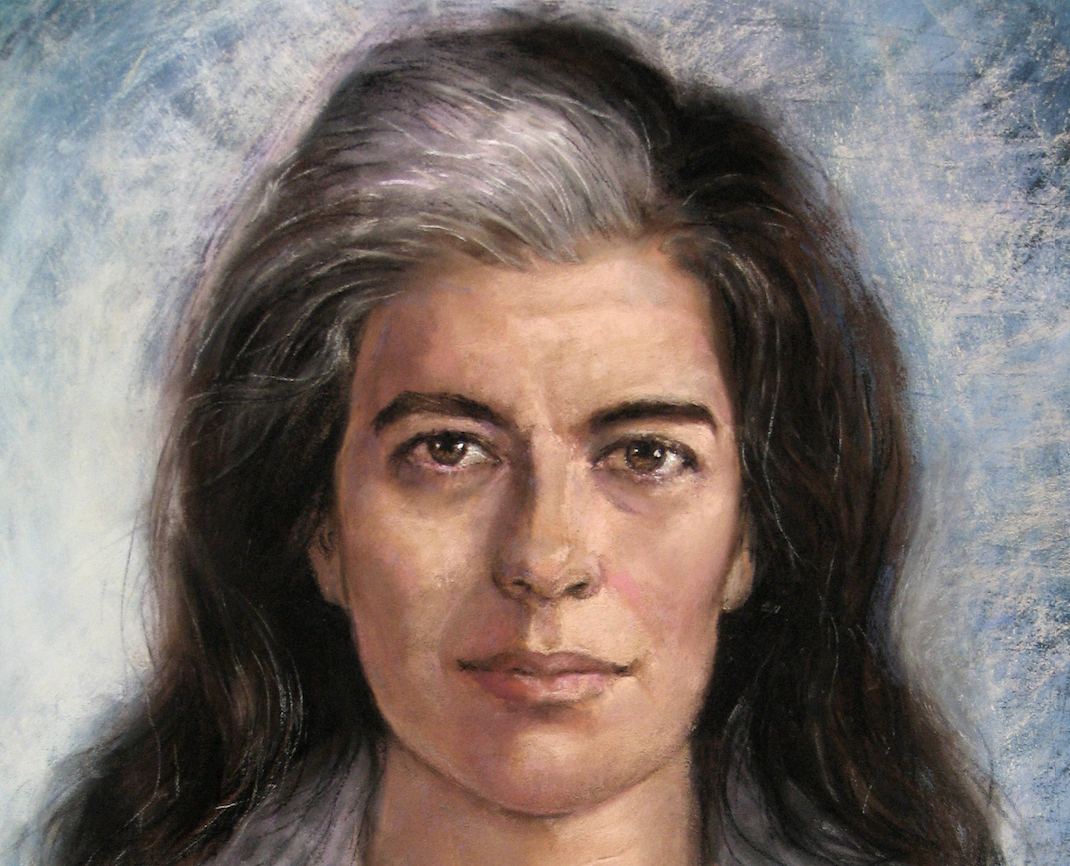

In 2010, Patti Smith won a National Book Award for her memoir Just Kids, making her, by my count, the only Rock and Roll Hall of Fame member to land that prize. Of course, she’s also the only person I can think of who has appeared in both a movie by Jean-Luc Godard (Film Socialisme) and an episode of Law and Order. And she’s definitely the only rocker out there who has a personal invite from the Pope to play at the Vatican.

Back in the mid-‘70s, Smith fused the noise and urgency of punk rock with spoken word poetry and created something unlike anything before or since. She performed with such intensity on stage that she looked like a modern day shaman in the midst of an ecstatic revelry. Yet she had a literary sensibility that made her stand apart from most of her fellow proto-punks at CBGBs. (The Ramones are awesome but no one is going to parse the lyrics of “Beat on the Brat with a Baseball Bat.”) The B‑side track of Smith’s first single, “Piss Factory,” describes the unrelenting tedium she experienced working at a factory before she swiped a copy of Illuminations by French poet Arthur Rimbaud.

While making Film Socialisme with Godard, she conceived of her latest album, Banga, released in 2012. When she started writing songs, she was, as she said in an interview, very interested in Russian culture.

I like my travels to be akin with my studies, and so when I started being smitten with Bulgakov and started reading a lot of Russian literature and then watching a lot of Tarkovsky, being very immersed in Russian culture, I got some jobs in Russia. … But I’ve always done that. We have very idiosyncratic tours – I always make sure that the band does well financially, but a lot of our tours are based on things that I’m studying, and I’ll make choices as to where we go so that I can see something special.

The title track of the work, Banga, is taken from a minor character in Mikhail Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita – Pontus Pilate’s extremely loyal dog who waited centuries for his master to come to heaven. Fun fact: Johnny Depp played drums on this track.

According to the liner notes, the album’s first single, “April Fool” was inspired by novelist Nikolai Gogol. As John Freeman notes in the Moscow Times, a number of lines from the song evoke the writer.

We’ll race through alleyways in tattered coats” is a fairly clear reference to Gogol’s short story “The Overcoat,” while “we’ll burn all of our poems” begs to be considered a nod to the fact that Gogol famously burned the second volume of his great novel “Dead Souls.” That work, one of Russia’s funniest and darkest, is conjured in the lines, “We’ll tramp through the mire when our souls feel dead. With laughter we’ll inspire them back to life again.

And the track “Tarkovsky (The Second Stop Is Jupiter)”, not surprisingly, evokes images from the films of cinematic auteur Andrei Tarkovsky – specifically, his metaphysical sci-fi epic Solaris along with Ivan’s Childhood. Hear the track at the top of this post, and watch Tarkovsky’s films online here.

In case you thought that the album was just about Russians, her song “This is the Girl” is about the life and death of Amy Winehouse, “Fuji-San” is a tribute to the massive 2011 Tohoku earthquake, and “Nine” is a birthday present to Johnny Depp.

Related Content:

Watch Patti Smith Read from Virginia Woolf, and Hear the Only Surviving Recording of Woolf’s Voice

See Patti Smith Give Two Dramatic Readings of Allen Ginsberg’s “Footnote to Howl”

Patti Smith Plays Songs by The Ramones, Rolling Stones, Lou Reed & More on CBGB’s Closing Night (2006)

Patti Smith Documentary Dream of Life Beautifully Captures the Author’s Life and Long Career (2008)

Jonathan Crow is a Los Angeles-based writer and filmmaker whose work has appeared in Yahoo!, The Hollywood Reporter, and other publications. You can follow him at @jonccrow. And check out his blog Veeptopus, featuring lots of pictures of badgers and even more pictures of vice presidents with octopuses on their heads. The Veeptopus store is here.