Most people know that Mark Twain wrote about Jim and Huckleberry Finn navigating down the Mississippi. Less well known is that he occasionally dabbled in the burgeoning genre of science fiction. His 1898 short story “The Great Dark” is about a ship that sails across a drop of water on a microscope slide. His novel Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court is one of the first to explore time travel. And, in a short story called “From The ‘London Times’ in 1904,” Twain predicted the internet. In 1898. Read it here.

Set five years into the future, the story starts off as a crime mystery. Clayton, a quick-tempered army officer, is accused of murdering Szczepanik, the inventor of a new and promising device called the Telelectroscope. The tale’s unnamed narrator describes it like this:

As soon as the Paris contract released the telelectroscope, it was delivered to public use, and was soon connected with the telephonic systems of the whole world. The improved ‘limitless-distance’ telephone was presently introduced and the daily doings of the globe made visible to everybody, and audibly discussable too, by witnesses separated by any number of leagues.

That sounds a lot like social media. Mark Twain dreamed up Twitter and Youtube during the Grover Cleveland administration.

Facing the hangman’s noose, Clayton asks for, and receives, a telelectroscope for his cell. As the narrator describes Clayton’s telelectroscopic revelry, it sounds uncannily like a bored cubicle dweller surfing the web at work.

…day by day, and night by night, he called up one corner of the globe after another, and looked upon its life, and studied its strange sights, and spoke with its people, and realized that by grace of this marvelous instrument he was almost as free as the birds of the air, although a prisoner under locks and bars. He seldom spoke, and I never interrupted him when he was absorbed in this amusement. I sat in his parlor and read, and smoked, and the nights were very quiet and reposefully sociable, and I found them pleasant. Now and then I would hear him say ‘Give me Yedo;’ next, ‘Give me Hong-Kong;’ next, ‘Give me Melbourne.’ And I smoked on, and read in comfort, while he wandered about the remote underworld, where the sun was shining in the sky, and the people were at their daily work.

The story itself is an admittedly minor work by the master of American fiction. In its last third, the story abruptly turns into a surprisingly sour satire about the sad state of our legal system. As Clayton is getting marched to the gallows, the narrator spots the guy Clayton supposedly murdered on the telelectroscope screen, standing in a crowd for the coronation of the new “Czar” of China. Even though no crime took place, Clayton is still sentenced to hang.

“From The ‘London Times’ in 1904” contains two long-running themes in Twain’s work and life. One is the absurdity of the courts – see, for example “The Facts in the Great Landslide Case.”

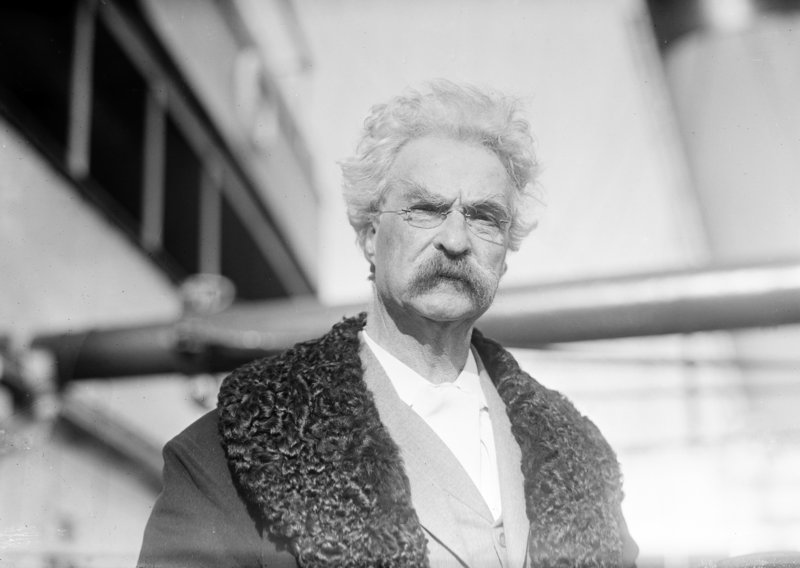

And the other is a fascination with technology. In spite of his folksy image, he was, as they say now, an early adopter. He was the first in his neighborhood to get a telephone. He may or may not have been the first major author to use a typewriter to write a novel. He lost his shirt investing in a Victorian-era start up hawking an exceedingly complex printing press called the Paige Compositor. And he allowed himself to be filmed by Thomas Edison in 1909, a year before his death.

One wonders what he would have thought of his telelectroscope in action.

Note: The character Szczepanik mentioned above was clearly named after a Polish inventor, Jan Szczepanik, who talked about creating a “telectroscope,” in the late 19th century. However, if you read a report in The New York Times in 1898, it becomes apparent that Szczepanik’s “telectroscope” wasn’t as visionary as what Twain had in mind.

Related Content:

Mark Twain Wrote the First Book Ever Written With a Typewriter

Mark Twain Shirtless in 1883 Photo

Mark Twain Captured on Film by Thomas Edison in 1909. It’s the Only Known Footage of the Author.

Jonathan Crow is a Los Angeles-based writer and filmmaker whose work has appeared in Yahoo!, The Hollywood Reporter, and other publications. You can follow him at @jonccrow. And check out his blog Veeptopus, featuring lots of pictures of vice presidents with octopuses on their heads. The Veeptopus store is here.