Warner Bros.

How often does a film adaptation of a novel you love meet your expectations? Circle one: A) Always B) Often C) Rarely D) Never.

I’m guessing most people choose C, with a few falling solidly in the perennially disappointed D camp. There are, of course, those very few films that rise so far above their source material that we needn’t speak of the novel at all. I can think of one off the top of my head, involving a certain well-dressed mobster family.

Then there are adaptations of books that depart so far from the source that any comparison seems like a wasted exercise. Spike Jonze’s Adaptation is one intentional example, one that gleefully revels in its meta-poetic license-taking.

Perhaps no single author save Shakespeare, Jane Austen, or Stephen King has had as many of his works adapted to the screen as sci-fi visionary Philip K. Dick. The results vary, but the force of Dick’s imagination seems to make every cinema version of his novels worth watching, I’d argue.

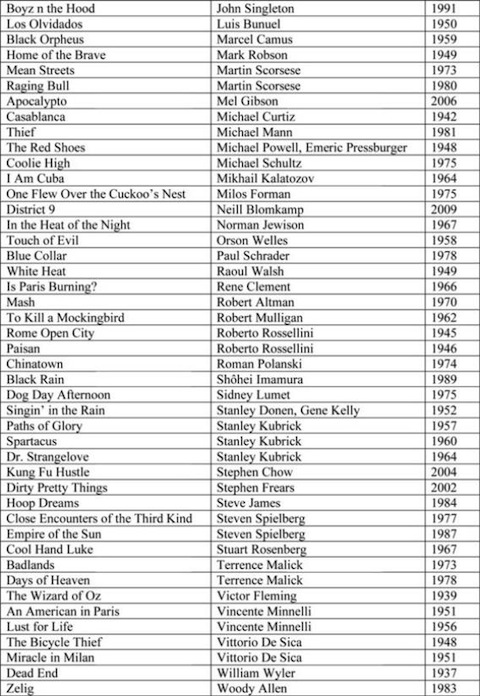

But all this talk of adaptation brings us to the question that the internet must ask of every subject under the sun: what are nth best films made from novels—list them, damn you! Okay, well, you won’t get just my humble opinion, but the collective votes of hundreds of Guardian readers, circa 2006, when writers Peter Bradshaw and Xan Brooks took a poll, then posted the results as “The Big 50.”

The list includes those dapper mafiosi, but, as I said, I’m not much inclined—nor was Francis Ford Coppola—to Mario Puzo’s novel. But there are several films on the list made from books I do like quite a bit. In the 15 picks below, I like the movies almost or just as much. These are films from The Guardian’s big 50 that I feel do their source novels justice. Go ahead and quibble, rage, or even agree in the comments below—or, by all means, make your own suggestions of cases where film and book meet equally high standards, whether those examples appear on “The Big 50” or not.

1. A Clockwork Orange (1971)

Stanley Kubrick’s take on Anthony Burgess’ 1962 dystopian fable replicates the highly disorienting experience of traversing a fictional world through the eyes of a Beethoven-loving, Nadsat-speaking, sociopath. Malcolm McDowell gives the performance of his career (see above). So distinctive is the set design, it inspired a chain of Korova Milk Bars. Burgess himself had a complicated relationship with the film and its director. Praising the adaptation as brilliant, he also found its bleak, sardonic ending, and omission of the novel’s redemptive final chapter—also missing from U.S. editions of the book prior to 1986—troubling. The film’s relentless ultraviolence, so disturbing to many a viewer, and many a religious organization, also disturbed the author who imagined it.

2. One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975)

A film adaptation with an even more bravado ensemble cast (Danny DeVito, Brad Dourif, Louise Fletcher, Christopher Lloyd) and incredibly charismatic—and dangerous—lead, Jack Nicholson, Milos Forman’s Cuckoo’s Nest stands perfectly well on its own. But lovers of Ken Kesey’s madcap novel have many reasons for favorable comparison. One vast difference between the two, however, lies in the narrative point-of-view. The book is narrated by willfully silent Chief Bromden—the film mostly takes McMurphy’s point-of-view. Without a voice-over, it would have been near-impossible to stay true to the source, but the result leaves the novel’s narrator mostly on the sidelines—along with many of his thematic concerns. Nonetheless, actor Will Sampson imbues the towering Bromden with deep pathos, empathy, and comic stoicism. When he finally speaks, it’s almost like we’ve been hearing his voice all along (see above).

3. To Kill a Mockingbird (1962)

“Miss Jean Louise, stand up! Your father’s passing.” If this scene (above), doesn’t choke you up just a little, well… I don’t really know what to say.… The sentimental adaptation of the reclusive Harper Lee’s only novel is flawed, righteous, and loveable. Gregory Peck is Atticus Finch (and as far as adaptations go—despite the brave attempts of many a fine actor—is Ahab as well). And the young Mary Badham is Scout. Robert Duvall makes his screen debut as kindly shut-in Boo Radley, audiences learn how to pronounce “chiffarobe”…. It’s as classic a piece of work as the novel—seems almost impossible to separate the two.

4. Apocalypse Now (1979)

Francis Ford Coppola and screenwriter John Milius—the Hollywood character so well caricatured by John Goodman in The Big Lebowski—transform Joseph Conrad’s lean 1899 colonialist novella Heart of Darkness into a grandiose, barely coherent, psychedelic tour-de-force set in the steaming jungles of Vietnam. Brando glowers in shadow, Robert Duvall strikes hilariously macho poses, Martin Sheen genuinely loses his mind, and a coked-up, manic Dennis Hopper shows up, quotes T.S. Eliot, and nearly upstages everyone (above). Roger Ebert loved the even longer, crazier Redux, released in 2001, saying it “shames modern Hollywood’s timidity.” Novelist Jessica Hagedorn fictionalized the movie’s legendary making in the Philippines. How much is left of Conrad? I would say, surprisingly, quite a bit of the spirit of Heart of Darkness survives—maybe even more than in Nicolas Roeg’s straightforward 1994 adaptation with John Malkovich as Kurtz and Tim Roth as Marlow.

5. Trainspotting (1996)

Danny Boyle’s adaptation of Irvine Welsh’s addiction-themed first novel—or rather collection of interlinked stories—about a scrappy bunch of Scottish lowlifes may be very much a product of its moment, but its hard to imagine a more perfect screen realization of Welsh’s punk prose. Character-driven in the best sense of the phrase, Boyle’s comic Trainspotting manages the estimable feat of telling a story about drug addicts and criminal types that doesn’t feature any golden-hearted hookers, mournful interventions, self-righteous, didactic pop sociology, or other Hollywood drug-movie staples. A sequel—based on Welsh’s follow-up novel Porno—may be forthcoming.

And below are 10 more selections from The Guardian’s top 50 in which—I’d say—film and book are both, if not equally, great:

6. Blade Runner (1982)

7. Dr. Zhivago (1965)

8. Empire of the Sun (1987)

9. Catch-22 (1970)

10. Lolita (1962)

11. Tess (1979)

12. The Hound of the Baskervilles (1939)

13. The Day of the Triffids (1962)

14. Alice (1988)

15. Lord of the Flies (1963)

So, there you have it—my top 15 from The Guardian’s list of 50 best adaptations. What are your favorites? Look over their other 35—What glaring omissions deserve mention (The Shining? Naked Lunch? Dr. Strangelove? Lawrence of Arabia? The Color Purple?), which inclusions should be stricken, forgotten, burned? (Why, oh, why was the Tim Burton Charlie and the Chocolate Factory remake picked over the original?) All of the films mentioned are in English—what essential adaptations in other languages should we attend to? And finally, what alternate versions do you prefer to some of the most-seen adaptations of novels or stories?

Related Content:

44 Essential Movies for the Student of Philosophy

Stanley Kubrick’s List of Top 10 Films (The First and Only List He Ever Created)

700 Free Movies Online: Great Classics, Indies, Noir, Westerns, etc.

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness