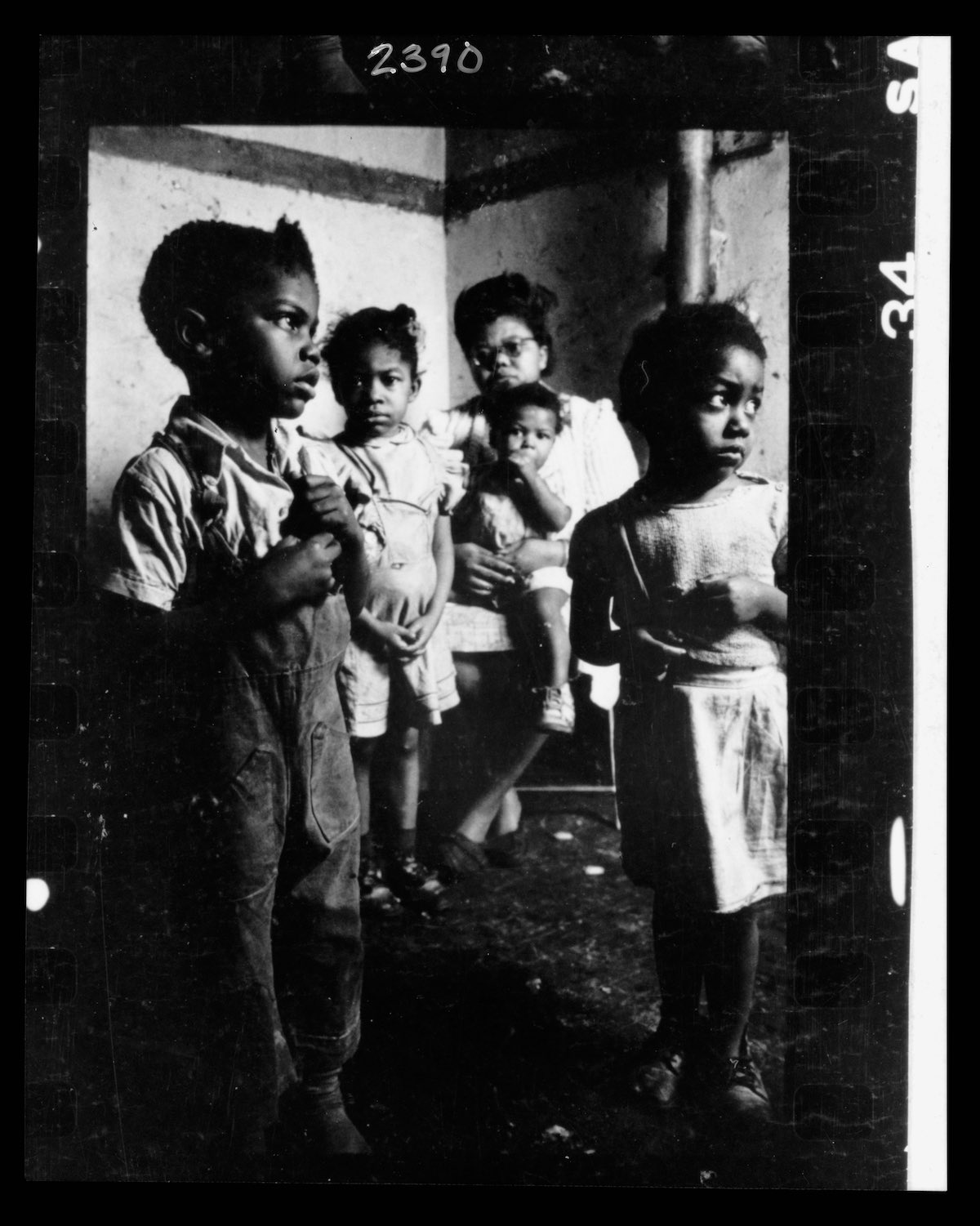

“Isaac Asimov on Throne” by Rowena Morrill via Wikimedia Commons

Where do ideas come from? The question has always had the potential to plague anyone trying to do anything worthwhile at any time in human history. But Isaac Asimov, the massively prolific and even more massively influential writer of science fiction and science fact, had an answer. He even, in one 1959 essay, laid out a method, though we, the general public, haven’t had the chance to read it until now. The MIT Technology Review has just published his essay on creativity in full, while providing a few contextualizing remarks from the author’s friend Arthur Obermayer, a scientist who invited Asimov on board an “out of the box” missile-defense research project at an MIT spinoff called Allied Research Associates.

“He expressed his willingness and came to a few meetings,” remembers Obermayer, but “he eventually decided not to continue, because he did not want to have access to any secret classified information; it would limit his freedom of expression. Before he left, however, he wrote this essay on creativity as his single formal input.” When Obermayer found it among his old files, he “recognized that its contents are as broadly relevant today as when [Asimov] wrote it” in 1959, describing as they do “not only the creative process and the nature of creative people but also the kind of environment that promotes creativity.” Whether you write sci-fi novels or do military research, make a web series, or work on curing Ebola, you can put Asimov’s methods to use.

Asimov first investigates the origin of ideas by looking to The Origin of Species. Or rather, he looks to what you find within it, “the theory of evolution by natural selection, independently created by Charles Darwin and Alfred Wallace,” two men who “both traveled to far places, observing strange species of plants and animals and the manner in which they varied from place to place,” both “keenly interested in finding an explanation for this,” and both of whom “failed until each happened to read Malthus’s ‘Essay on Population.’ ” He finds that “what is needed is not only people with a good background in a particular field, but also people capable of making a connection between item 1 and item 2 which might not ordinarily seem connected.” Evolutionary theory seems obvious only in retrospect, he continues, as

The history of human thought would make it seem that there is difficulty in thinking of an idea even when all the facts are on the table. Making the cross-connection requires a certain daring. It must, for any cross-connection that does not require daring is performed at once by many and develops not as a “new idea,” but as a mere “corollary of an old idea.”

It is only afterward that a new idea seems reasonable. To begin with, it usually seems unreasonable. It seems the height of unreason to suppose the earth was round instead of flat, or that it moved instead of the sun, or that objects required a force to stop them when in motion, instead of a force to keep them moving, and so on.

A person willing to fly in the face of reason, authority, and common sense must be a person of considerable self-assurance. Since he occurs only rarely, he must seem eccentric (in at least that respect) to the rest of us. A person eccentric in one respect is often eccentric in others.

Consequently, the person who is most likely to get new ideas is a person of good background in the field of interest and one who is unconventional in his habits. (To be a crackpot is not, however, enough in itself.)

Once you have the people you want, the next question is: Do you want to bring them together so that they may discuss the problem mutually, or should you inform each of the problem and allow them to work in isolation?

The essay puts forth an argument for isolation (“Creation is embarrassing. For every new good idea you have, there are a hundred, ten thousand foolish ones, which you naturally do not care to display”) and a set of best practices for group idea generation, as implementable in the Allied Research Associates of the 1950s as in any organization today. If you can’t trust Asimov on this subject, I don’t know who you can trust, but consider supplementing this newfound essay with Ze Frank’s thematically related video “Brain Crack” (linguistically NSFW, though you can watch the PG version instead), which deals, in an entirely different sensibility, with the question of where ideas come from:

via io9

Related Content:

David Lynch Explains How Meditation Enhances Our Creativity

Malcolm McLaren: The Quest for Authentic Creativity

Isaac Asimov Predicts in 1964 What the World Will Look Like Today — in 2014

John Cleese’s Philosophy of Creativity: Creating Oases for Childlike Play

Free: Isaac Asimov’s Epic Foundation Trilogy Dramatized in Classic Audio

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on cities, language, Asia, and men’s style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.