We’ve all got those friends or family members who consider “modern art” a form of torture. Next time they complain about an exhibition you bring them to, just tell them how relieved they should feel that they didn’t fight in the Spanish Civil War — not just for the obvious reasons; they could have found themselves subject not just to actual torture, but torture directly inspired by modernist aesthetic principles. “A Spanish art historian has found evidence that suggests some Civil War jail cells were built like 3‑D modern art paintings in order to torture prisoners,” reports BBC News. “The cells were built in 1938 for the republican forces fighting General Franco’s Fascist Nationalist army, who eventually won power.” The finding comes from historian Jose Milicua, who discovered references to these modern-art cells among court papers from “the 1939 trial of French anarchist Alphonse Laurencic, a republican, by a Franco-ist military court.”

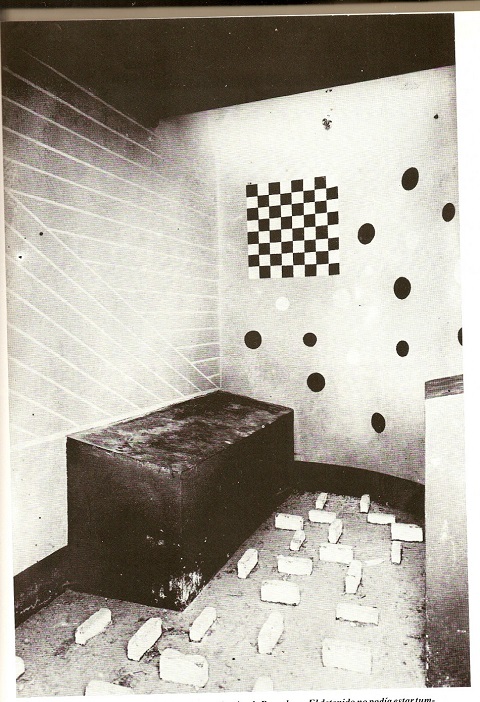

“During the trial,” the BBC article continues, “Laurencic revealed he was inspired by modern artists, such as surrealist Salvador Dali and Bauhaus artist Wassily Kandinsky” to create the six-foot-by-four-foot cells placed secretly in Barcelona (see a re-creation above), which featured “sloping beds at a 20-degree angle that were almost impossible to sleep on,” “irregularly shaped bricks on the floor that prevented prisoners from walking backwards or forwards,” walls “covered in surrealist patterns designed to make prisoners distressed and confused,” and lighting effects “to make the artwork even more dizzying.” Evidence also indicates that, elsewhere in Spain, Nationalist prisoners “were forced to watch Salvador Dali and Luis Bunuel’s film Un Chien Andalou,” especially an endless loop of its “graphic sequence of an eyeball being cut open” (at the top of the post).

Ironically, those imprisoned in such cells would have wound up there in the name of their fascist cause, which like the Franco-backing Nazi regime in Germany, considered modernism “degenerative.” Presumably, they didn’t leave their imprisonment with any more sympathetic idea of modern art than the one they’d gone in with. “A subcurrent of shock and provocation has always lurked within avant-garde art, which deliberately sets out to challenge bourgeois convention and to elicit a strong response” writes the New York Times’ John Rockwell. “My own experience has been that opponents of new art are much too quick to presume provocation, let alone provocation intended literally to torture. Still, there can be no doubt that outrage was and is a goal of some artists, even if they rarely pushed it to the logical extreme that Laurencic took it.” You can learn more about this unusually artistic form of warfare in this All Things Considered interview with art historian Victoria Combalia. (Listen below.) And do try to suppress those fantasies of throwing your more Philistine acquaintances in there for an hour or two.

Related Content:

Restored Version of Un Chien Andalou: Luis Buñuel & Salvador Dalí’s Surreal Film (1929)

The Nazi’s Philistine Grudge Against Abstract Art and The “Degenerate Art Exhibition” of 1937

How the CIA Secretly Funded Abstract Expressionism During the Cold War

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on cities, language, Asia, and men’s style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.