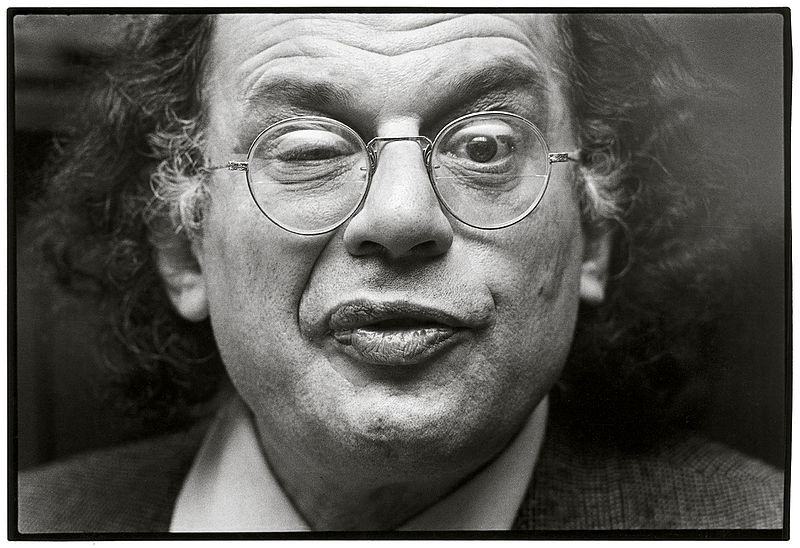

In the fall of 1965, six months after Bob Dylan freaked out the folkies at Newport, he sat down with Village Voice music critic and columnist Nat Hentoff for an interview for Playboy. Like Dylan himself, the resulting conversation, as published in February, 1966, is by turns illuminating and completely confounding. Topics shift abruptly, words take on unfamiliar meanings, and for all of the many strong opinions Dylan seems to express, it’s remarkable how little he actually seems to say, since he takes back almost everything as soon as he says it.

The verbal tangles of his answers take many philosophical turns. Dylan defines the contemporary art scene, saying “Art, if there is such a thing, is in the bathrooms; everybody knows that. […] I spend a lot of time in the bathroom. I think museums are vulgar. They’re all against sex.” Asked “why rock ‘n’ roll has become such an international phenomenon,” Dylan waxes ontological: “I can’t really think that there is any rock ’n’ roll. Actually, when you think about it, anything that has no real existence is bound to become an international phenomenon.”

The bizarre nature of the published exchange is classic, comically aloof, mid-sixties Dylan—so much in character we can imagine Cate Blanchett’s serpentine Dylan in I’m Not There saying the lines. But the print version of the conversation is streamlined and lucid compared to the unedited, taped conversation Dylan and Hentoff had the year prior before an editor pared it down. As music site All Dylan has it, “to call them versions ignores the fact that they are totally different interviews.”

The original take, which you can hear above in two parts, was much messier, and stranger. Dylan often sounds like he’s not answering questions so much as putting words together in sentence-like forms. His speech takes on the qualities of abstract expressionism—recursive, and pointedly vague. We might assume he’s really stoned, except for a long-winded speech about how passé it is to smoke pot.

Well, I never felt as if there’s an answer through pot. I don’t want to make this, kind of, a drug interview or anything, like. LSD like… once you take LSD a few times… I mean, LSD is a medicine. You know, you take it and you know… you don’t really have to keep taking it all the time. It’s nothing like that. It’s not that kind of thing, you know, whereas pot, you know, nobody’s got any answers through pot. Pot’s, you know, not that kind of thing. I’m sure that the people that say that the people who figure they got their answers through pot, first of all, those people who say that, they’re just inventing something. And the people that really actually think that they got their answers through pot, probably never even smoked pot, you know. I mean, it’s like… pot is, you know…who smokes pot any more, you know, anyway?

Ever noncommittal, Dylan deflects a question about his relationship with Johnny Cash, saying “I can’t really talk about it too much,” but assuring Hentoff that he likes Cash “a lot. I like everything he does really.” If Dylan gives as much as he takes away in the published interview, he does so doubly in this unedited version, and it’s oddly fascinating, even—and especially—when he decides to stop making words make sense. The taped interview was, in fact, the second interview Hentoff conducted with Dylan. After seeing an edited transcript of the first attempt, Dylan insisted that Hentoff interview him again over the phone. Hentoff turned on his tape recorder and immediately “realized I was going to be the straight guy,” he tells John Whitehead, “Dylan was improvising surrealistically and very funny.”

Vulture ranks the Playboy interview at number one in their list of “The 10 Most Incomprehensible Bob Dylan Interviews of All Time.” It must have been a tough call. At number 10, they have the Time magazine interview from that same year, which you can see in the clip above from 1967’s Don’t Look Back. Dylan is confrontational, almost theatrically angry, but he is mostly clear on the details. He ends the interview with a cryptic joke, comparing himself to opera singer Enrico Caruso: “I happen to be just as good as him—a good singer. You have to listen closely, but I hit all those notes.”

via All Dylan

Related Content:

Bob Dylan Reads From T.S. Eliot’s Great Modernist Poem The Waste Land

Two Legends Together: A Young Bob Dylan Talks and Plays on The Studs Terkel Program, 1963

Bob Dylan Finally Makes a Video for His 1965 Hit, “Like a Rolling Stone”

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness.

MP3

MP3