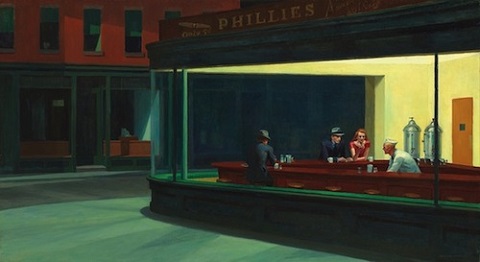

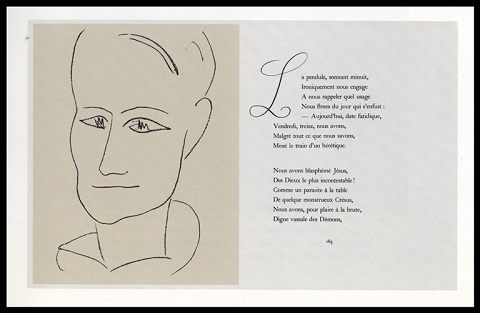

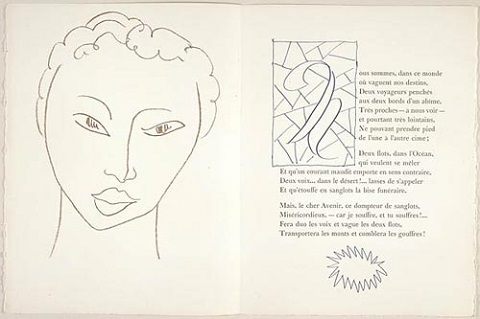

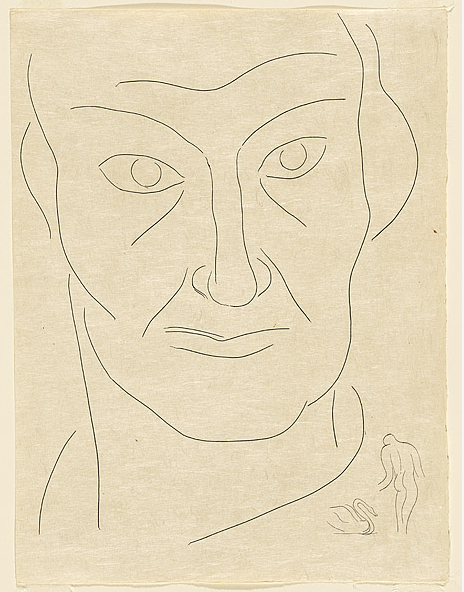

Images of Derrida and Coleman, via Wikimedia Commons

This most certainly ranks as one of my favorite things on the internet, and I dearly wish we had audio to share with you, though I doubt any exists. What we do have is an English translation from the French of an interview that originally took place in English between philosopher Jacques Derrida and jazz great Ornette Coleman.

Now there are those who dismiss Derrida—who consider his methods fraudulent. If you’re one of them, this is obviously not for you. For those who appreciate the turns of his thought, and the fascinating possibilities inherent in a Derridian approach to jazz improvisation, not to mention the convergences and points of conflict between these two disparate cultural figures, read on.

The interview took place in 1997, “before and during Coleman’s three concerts at La Villette, a museum and performing arts complex north of Paris that houses, among other things, the world-renowned Paris Conservatory.” As I mentioned, the two spoke in English but, as translator Timothy S. Murphy—who worked with a version published in the French magazine Les Inrockuptibles—notes, “original transcripts could not be located.” Curiously, at the heart of the conversation is a discussion about language, particularly “languages of origin.” In answer to Derrida’s first question about a program Coleman would present later that year in New York called Civilization, the saxophonist replies, “I’m trying to express a concept according to which you can translate one thing into another. I think that sound has a much more democratic relationship to information, because you don’t need the alphabet to understand music.”

As one example of this “democratic relationship,” Coleman cites the relationship between the jazz musician and the composer—or his text: “the jazz musician is probably the only person for whom the composer is not a very interesting individual, in the sense that he prefers to destroy what the composer writes or says.” Coleman goes on later in the interview to clarify his ideas about improvisation as democratic communication:

[T]he idea is that two or three people can have a conversation with sounds, without trying to dominate or lead it. What I mean is that you have to be… intelligent, I suppose that’s the word. In improvised music I think the musicians are trying to reassemble an emotional or intellectual puzzle in which the instruments give the tone. It’s primarily the piano that has served at all times as the framework in music, but it’s no longer indispensable and, in fact, the commercial aspect of music is very uncertain. Commercial music is not necessarily more accessible, but it is limited.

Translating Coleman’s technique into “a domain that I know better, that of written language,” Derrida ventures to compare improvisation to reading, since it “doesn’t exclude the pre-written framework that makes it possible.” For him, the existence of a framework—a written composition—even if only loosely referenced in a jazz performance, “compromises or complicates the concept of improvisation.” As Derrida and Coleman try to work through the possibility of true improvisation, the exchange becomes a fascinating deconstructive take on the relationships between jazz and writing. (For more on this aspect of their discussion, see “Deconstructin(g) Jazz Improvisation,” an article in the open access journal Critical Studies in Improvisation.)

The interview isn’t all philosophy. It ranges all over the place, from Coleman’s early days in Texas, then New York, to the impact of technology on music, to Coleman’s completely original theory of music, which he calls “harmolodics.” They also discuss globalization and the experience of growing up as a racial minority—an experience Derrida relates to very much. At one point, Coleman observes, “being black and a descendent of slaves, I have no idea what my language of origin was.” Derrida responds in kind, referencing one of his seminal texts, Monolingualism of the Other:

JD: If we were here to talk about me, which is not the case, I would tell you that, in a different but analogous manner, it’s the same thing for me. I was born into a family of Algerian Jews who spoke French, but that was not really their language of origin [… ] I have no contact of any sort with my language of origin, or rather that of my supposed ancestors.

OC: Do you ever ask yourself if the language that you speak now interferes with your actual thoughts? Can a language of origin influence your thoughts?

JD: It is an enigma for me.

Indeed. Derrida then recalls his first visit to the United States, in 1956, where there were “ ‘Reserved for Whites’ signs everywhere.” “You experienced all that?” he asks Coleman, who replies:

Yes. In any case, what I like about Paris is the fact that you can’t be a snob and a racist at the same time here, because that won’t do. Paris is the only city I know where racism never exists in your presence, it’s something you hear spoken of.

“That doesn’t mean there is no racism,” says Derrida, “but one is obliged to conceal it to the extent possible.”

You really should read the whole interview. The English translation was published in the journal Genre and comes to us via Ubuweb, who host a pdf. For more excerpts, see posts at The New Yorker and The Liberator Magazine. As interesting a read as this doubly-translated interview is, the live experience itself was a painful one for Derrida. Though he had been invited by the saxophonist, Coleman’s impatient Parisian fans booed him, eventually forcing him off the stage. In a Time magazine interview, the self-conscious philosopher recalled it as “a very unhappy event.” But, he says, “it was in the paper the next day, so it was a happy ending.”

Hear more of Coleman’s thoughts on language, sound, and technology in the 2008 interview above (see here for Part 2). The year previous, in another conjunction of the worlds of language and music, Coleman was awarded the Pulitzer Prize in music for his live album Sound Grammar, a title that succinctly expresses Coleman’s belief in music as a universal language.

Image of Ornette Coleman by Geert Vandepoele

Related Content:

Charles Mingus Explains in His Grammy-Winning Essay “What is a Jazz Composer?”

Derrida: A 2002 Documentary on the Abstract Philosopher and the Everyday Man

1959: The Year that Changed Jazz

How to Potty Train Your Cat: A Handy Manual by Charles Mingus

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness.