Before he directed such mind-bending masterpieces as Time Bandits, Brazil and Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, before he became short-hand for a filmmaker cursed with cosmically bad luck, before he became the sole American member of seminal British comedy group Monty Python, Terry Gilliam made a name for himself creating odd animated bits for the UK series Do Not Adjust Your Set. Gilliam preferred cut-out animation, which involved pushing bits of paper in front of a camera instead of photographing pre-drawn cels. The process allows for more spontaneity than traditional animation along with being comparatively cheaper and easier to do.

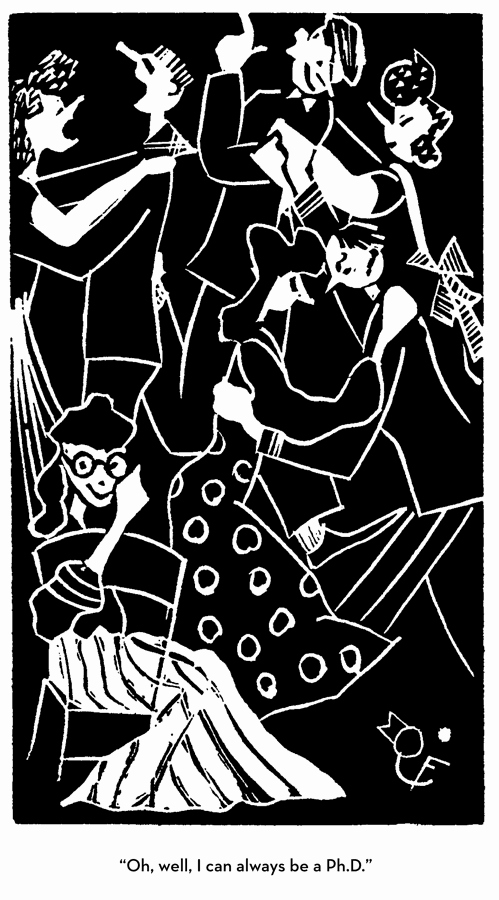

Gilliam also preferred to use old photographs and illustrations to create sketches that were surreal and hilarious. Think Max Ernst meets Mad Magazine. For Monty Python’s Flying Circus, he created some of the most memorable moments of a show chock full of memorable moments: A pram that devours old ladies, a massive cat that menaces London, and a mustached police officer who pulls open his shirt to reveal the chest of a shapely woman. He also created the show’s most iconic image, that giant foot during the title sequence.

On Bob Godfrey’s series Do It Yourself Film Animation Show, Gilliam delved into the nuts and bolts of his technique. You can watch it above. Along the way, he sums up his thoughts on the medium:

The whole point of animation to me is to tell a story, make a joke, express an idea. The technique itself doesn’t really matter. Whatever works is the thing to use. That’s why I use cut-out. It’s the easiest form of animation I know.

He also notes that the key to cut-out animation is to know its limitations. Graceful, elegant movement à la Walt Disney is damned near impossible. Swift, sudden movements, on the other hand, are much simpler. That’s why there are far more beheadings in his segments than ballroom dancing. Watch the whole clip. If you are a hardcore Python enthusiast, as I am, it is pleasure to watch him work. Below find one of his first animated movies, Storytime, which includes, among other things, the tale of Don the Cockroach. Also don’t miss, this video featuring All of Terry Gilliam’s Monty Python Animations in a Row.

Related Content:

The Best Animated Films of All Time, According to Terry Gilliam

Terry Gilliam: The Difference Between Kubrick (Great Filmmaker) and Spielberg (Less So)

The Miracle of Flight, the Classic Early Animation by Terry Gilliam

Jonathan Crow is a Los Angeles-based writer and filmmaker whose work has appeared in Yahoo!, The Hollywood Reporter, and other publications. You can follow him at @jonccrow.