The Sonny and Cher Show aired in the years right before I was born. Not only do I have no memory of it, of course, but I don’t believe I’ve ever seen an entire episode, either in re-runs or on the internet. Nevertheless, I immediately recognized the style of the show’s animator, English artist John David Wilson, when I encountered these music videos Wilson made for the singing comedy duo’s variety hour. Though a much less famous name, Wilson’s work seems to have animated the 70s in the way that R. Crumb’s illustrated the 60s. The opening sequences to iconic productions Grease and The Carol Burnett Show are Wilson’s, as are animations for Laugh In and cheesy Saturday morning kids’ show The Hudson Brothers Razzle Dazzle Show (best known now, perhaps, because of Hudson brother progeny Kate Hudson). Though Wilson’s career stretches back to the 50s—with work on Mr. Magoo, Peter Pan, and Lady and the Tramp—and into the 90s, with FernGully: The Last Rainforest, he seems to belong to the decade of “I Got You Babe” more so than any other.

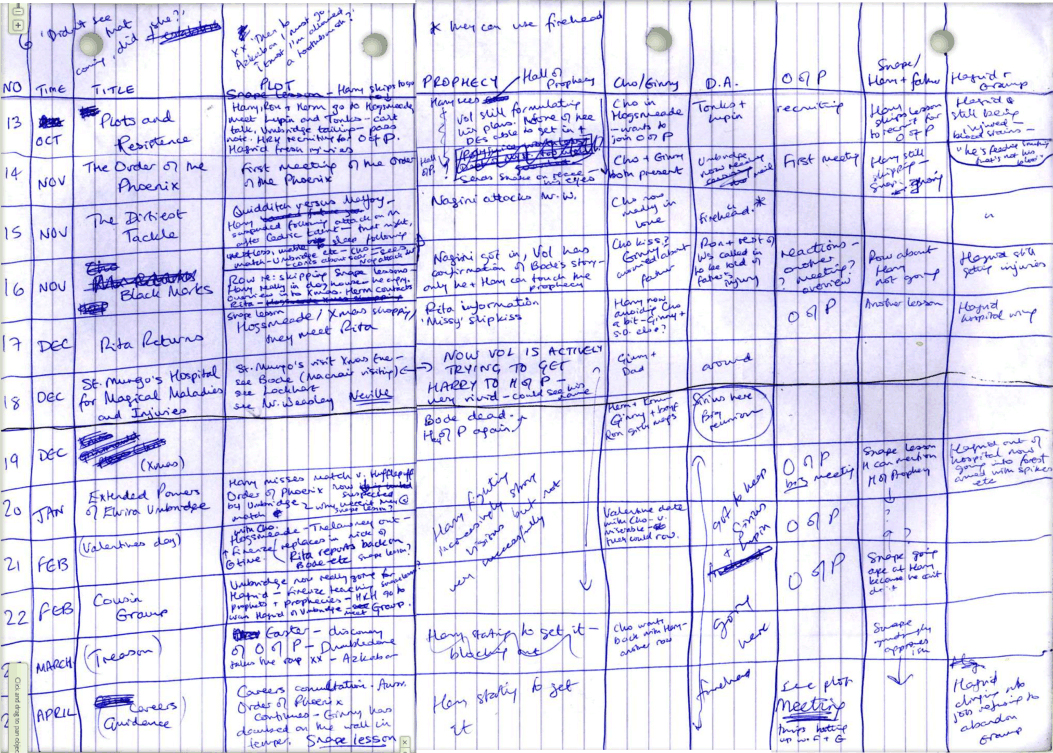

Drawn “in a simplistic, funky-looking style” and with goofy sound effects added (probably by the Sonny and Cher producers), Wilson’s animated films for Joni Mitchell’s “Big Yellow Taxi” (top), Jim Croce’s “Bad, Bad Leroy Brown” (above), and The Kinks “Demon Alcohol” (below, sung by Wayne Carpenter) enhance songs already rich with narrative. This, the blog Media Funhouse points out, was by design: “Wilson was wise to concentrate on the ‘story songs’ of the time, in order to create repeating characters and have the viewer ‘connect’ with the piece in a very short span of time.”

In most cases, Sonny and Cher’s vocals were dubbed over the original tracks, but in many of the animations that surfaced on VHS in the eighties and now appear on Youtube, the original songs have been restored, as in the two above. If you grew up with the show, you’ve surely seen at least a couple of these early music videos, a form Wilson is widely credited with pioneering. Beginning in the second season, Wilson’s company, Fine Arts Films, produced a total of fourteen animated shorts for the show.

The story-songs above of environmental degradation, tough street characters, and the depths of addiction seem so very characteristic of the period, though Wilson certainly animated more lighthearted pop fare, such as Melanie’s “Brand New Key” (sung here by Cher). For more of Wilson’s animated music videos, see Dangerous Minds or Media Funhouse, and for the full range of Wilson’s long career in animation, check out the website of the production company he founded, Fine Arts Films.

Related Content:

Watch Joni Mitchell Perform “Both Sides Now” on the First Episode of The Johnny Cash Show (1969)

A Short History of America, According to the Irreverent Comic Satirist Robert Crumb

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness