Image by Sound Opinions, via Flickr Commons

Roger Ebert seems to have resented star ratings, which he had to dish out atop each and every one of his hundreds upon hundreds of regular newspaper movie reviews. He also emphasized, every once in a while, his disdain for the “thumbs up” and “thumbs down” system that became his and Gene Siskel’s television trademark. And he could hardly ever abide that run-of-the-mill critic’s standby, the top-ten list. Filmgoers who never paid attention to Ebert’s career will likely, at this point, insist that the man never really liked anything, but those of us who read him for years, even decades, know the true depth and scope of his love for movies, a passion he even expressed, regularly, in list form. He did so for, as he put it, “the one single list of interest to me. Every 10 years, the ancient and venerable British film magazine, Sight & Sound, polls the world’s directors, movie critics, and assorted producers, cinematheque operators and festival directors, etc., to determine the Greatest Films of All Time.”

“Why do I value this poll more than others?” Ebert asks. “It has sentimental value. The first time I saw it in the magazine, I was much impressed by the names of the voters, and felt a thrill to think that I might someday be invited to join their numbers. I was teaching a film course in the University of Chicago’s Fine Arts Program, and taught classes of the top ten films in 1972, 1982 and 1992.” His dream came true, and when he wrote this reflection on sending in his list every decade, he did so a year nearly to the day before his death in 2013, making his entry in the 2012 Sight & Sound poll a kind of last top-ten testament:

- 2001: A Space Odyssey (Stanley Kubrick, 1968)

- Aguirre, the Wrath of God (Werner Herzog, 1972)

- Apocalypse Now (Francis Ford Coppola, 1979)

- Citizen Kane (Orson Welles, 1941)

- La dolce vita (Federico Fellini, 1960)

- The General (Buster Keaton, 1926) — free online

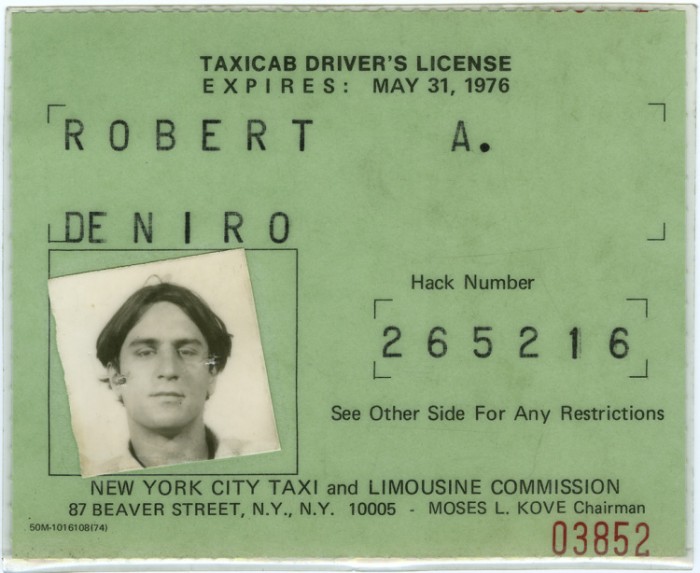

- Raging Bull (Martin Scorsese, 1980)

- Tokyo Story (Yasujirô Ozu, 1953)

- The Tree of Life (Terrence Malick, 2010)

- Vertigo (Alfred Hitchcock, 1958)

Deciding that he must vote for “one new film” he hadn’t included on his 2002 list, Ebert narrowed it down to two candidates: The Tree of Life and Charlie Kaufman’s Synecdoche, New York. “Like the Herzog, the Kubrick and the Coppola, they are films of almost foolhardy ambition. Like many of the films on my list, they were directed by the artist who wrote them. Like several of them, they attempt no less than to tell the story of an entire life. [ … ] I could have chosen either film — I chose The Tree of Life because it’s more affirmative and hopeful. I realise that isn’t a defensible reason for choosing one film over the other, but it is my reason, and making this list is essentially impossible, anyway.” That didn’t stop his cinephilia from prevailing — not that much ever could.

Related Content:

Roger Ebert Talks Movingly About Losing and Re-Finding His Voice (TED 2011)

The Two Roger Eberts: Emphatic Critic on TV; Incisive Reviewer in Print

Roger Ebert Lists the 10 Essential Characteristics of Noir Films

4,000+ Free Movies Online: Great Classics, Indies, Noir, Westerns, Documentaries & MoreColin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on cities, language, Asia, and men’s style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.